Skullbone Plains, south-east of Tasmania’s iconic Cradle Mountain, is one of the tracts of land purchased by the Tasmanian Land Conservancy (TLC), a not-for-profit organisation devoted to conserving and protecting vulnerable land. The aptly acronymed TLC has raised millions of dollars to acquire and secure the habitat of critically endangered species of plants and animals.

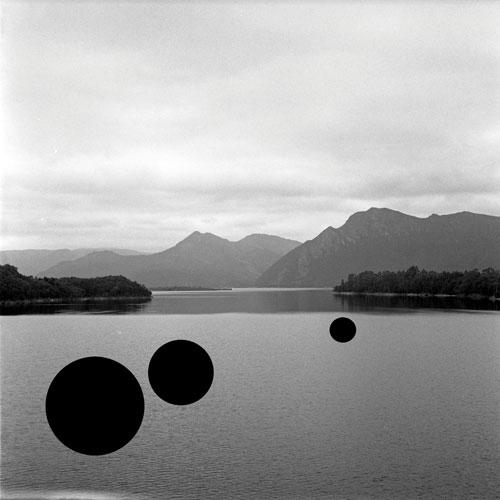

For four days in the heat of summer 2013, eleven established and early career artists were invited to roam, collect, sketch, photograph, talk, think, eat, drink and sleep in this landscape. The artists were joined on this retreat by environmental scientists, writer Richard Flanagan and poet Pete Hay. The latter, in a terrific contribution to the exhibition catalogue, conjures the complexity of this seemingly grim place and shines a bright light on the false dichotomy between culture and nature. For Skullbone Plains, as its name suggests, is not the usual wilderness with sublime mountain ranges and exquisite specimens of ferns, fagus and gnarly Huon pine that have become perhaps overly familiar via the exquisite photography of Peter Dombrovkis. Rather, this is an unimposing landscape of button grass and peatlands, with distant ranges obscured by eucalypt scrub.

A little over a year later, the creative responses of each artist have been gathered in a rich and insightful exhibition overseen by curator Catherine Wolfhagen and artist Philip Wolfhagen.

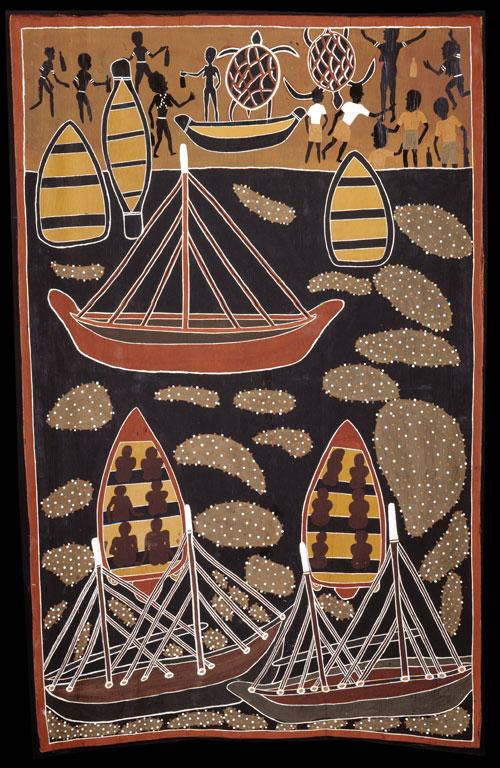

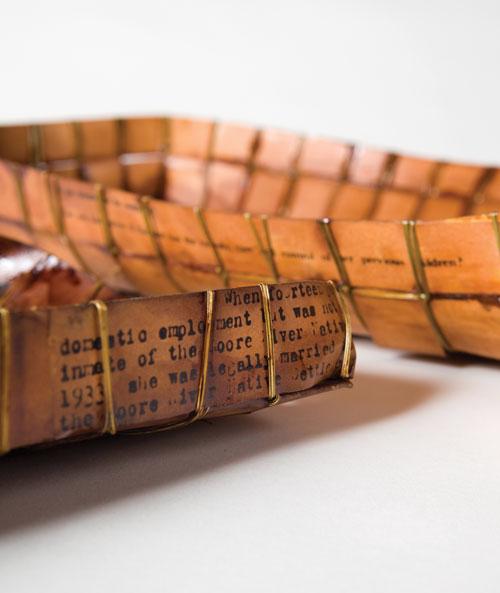

Julie Gough invites memories of a complex layering of stories – good, bad and indifferent – echoes of footsteps are triggered by a single desiccated leather shoe, stepping back in time to the Aboriginality inevitably enmeshed in the land. In concert, Megan Walch’s canvases either reflect the outward onto a watery surface or keep watch on the outside world from ancient watery depths.

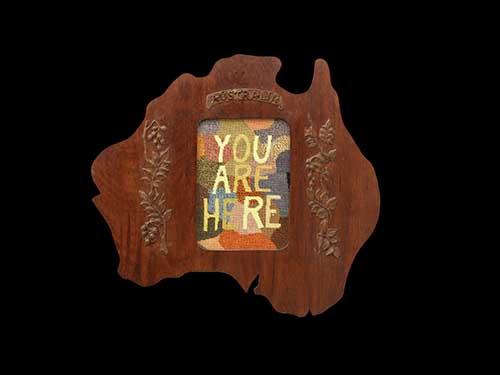

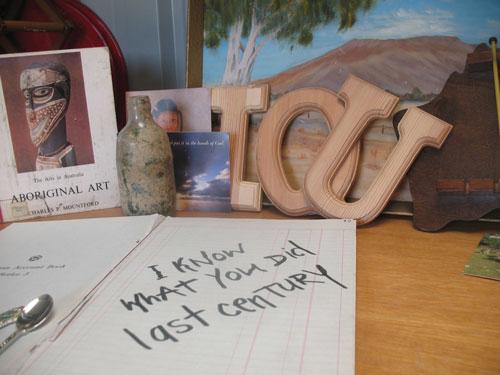

For Tim Burns, Philip Hunter, Richard Wastell and Wolfhagen beauty is unearthed in the poetics of colour, mark and pattern inherent in the land and its flora. But a disturbing absence resonates through many of the works. The button grass, a by-product of fire-stick farming, acknowledges a deep Aboriginal presence, and the name of the place casts a heavy pall over everything. Imants Tillers endeavours to name up this absence directly as he grapples with the inadequacy to do justice to the deathly quiet. But misplaced use of Tasmanian Aboriginal language and shadows of Western Desert mark making are inadequate attempts to remember a people who were all but obliterated.

Another theme is the landscape of small and seemingly insignificant things that in a more imposing environment would disappear – out of sight, out of mind. Janet Laurence literally shrouds her collection of specimens in a veil of forgetting. She refutes the assumption that it is all right to destroy these environments before we know what they are. Vera Möller’s tiny displaced, misplaced, replaced hybrid species herald the unseen changes that such an irresponsible approach could bring. John Wolseley engages this organic space too, working directly with the materiality of sphagnum moss and collaborating with nature’s frottage to extract an analytical line of reasoning.

Joel Crosswell’s creatures are of an altogether different order and yet they hold something of all the works. His nocturnal meanderings conjure hybrid galaxia, morphing with either the layers of characters from the location’s past or with this band of artists struggling to come to grips with what the place means.

Entwining this exhibition are threads connecting divergent definitions of “long term”. Scientists understand the concept in millions and billions of years. Aboriginal people can remember tens of millennia. Some think of generations. For others the length of their lifetime is all that matters; and there are people for whom the daily metre of the stock exchange is too much. The Skullbone Experiment interrogates these competing definitions and invites us into conversations about what it means to inhabit this extraordinary planet.