Ghostscapes is an exhibition disturbing enough – and beautiful enough – to goad us into thinking more boldly about “home” and what lies beneath and before.

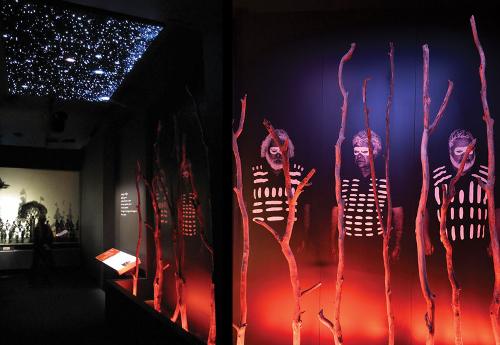

Ply-wood walls configure the exhibition space as a “home” with an entrance corridor, door mat and intimate spaces in which commonplace domestic items and embroideries seem to have soaked up the residue of past events and tragedies. The darkness is relieved by the warmth of domestic lighting, a sense of nostalgia, a dose of the ridiculous and the love implicit in the time-consuming and exquisite making of these mini-memorials.

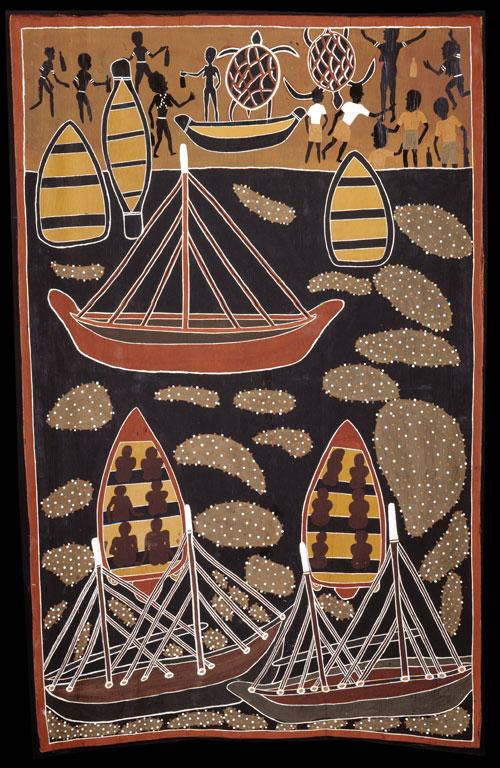

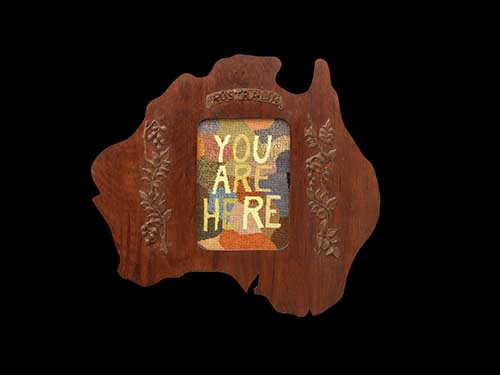

Viewers are implicated and reminded that there are no innocent bystanders. In the opening work the embroidered text YOU ARE HERE sits within a map of Australia, an old wooden frame, a piece of Australiana that in this context interrogates past and present notions of nationhood or “home”. Ghosts from other times and other places are evoked – settlers who in difficult circumstances hung curtains and stitched tablecloths with sentimental images of birds and flora to make and reshape their homes, to reconfigure their reality. The stitched background echoes Horton’s Map of Aboriginal Australia – a reminder that whatever colonialism was and is, it has made this place unsettled and unsettling. “Home” for Sera Waters is a haunted place; forever frontier territory. Moving through the exhibition you sense fear as the baseline that underscores a world in which physical geography and cultural settings contend and combine.

At the end of the entrance corridor hangs Stumped: A family gathering. In front of the soft green leaves of vintage wallpaper (from Waters’ childhood home) and hung from a found bill holder are four different-sized kangaroo tails. The stumps are precisely embroidered to resemble stumps of trees. Waters writes on her website: “When I think of stumps, I think tree stumps, bodily stumps and life stumped, all literally cut short. Survival can be brutal.”

Drowning B(u)oy + B(u)oy’s washed up collections draws from the story of Waters’ great-grandmother who, standing on cliffs, was unable to reach and protect her young son from the sea. She remained paralysed and never walked again. Waters recalls from her grandmother’s home a portal window and frosted glass with ship scenes. And here in a port hole/ portal window/ embroidery circle is a painstakingly stitched, ghostly self-portrait. Is the water rising or is that hope on the horizon? Other elements are items Waters’ young sons might find washed up on shore – shells, buoys, a model ketch. Tucked inside the shells is a subtle audio installation – magpies calling to their young.

Geographic depressions become points of access to the subterranean world of dark happenings. In Lure the locals: Gentleman’s collectibles a George French Angas’ watercolour of the Devil’s Punchbowl in the Southeast of South Australia is shown on a screen embedded in the eye socket of a fishhead. Insect wings, a kangaroo skin, animal droppings are the elements of Australia that literally compose this highly considered meshing of narratives: contemporary and historical, autobiographical and fictional, art historical and ecological.

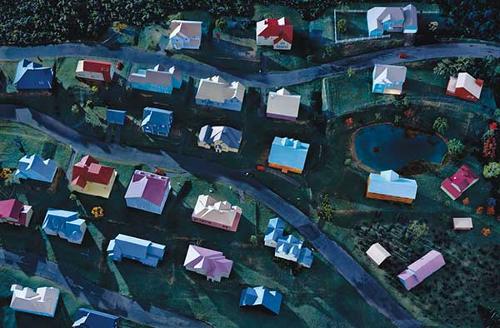

Like ducks on a lounge wall, Swarm Theory, a pale murder brings a bird’s-eye perspective to place. Waters’ recalls seeing a murder of crows fly in to land on a roof top as if in a premeditated, prearranged meeting. Pale, naked clay figures are shown in flight above a place, a map. Is that Adelaide? Governor Hindmarsh? Colonel Light? I consider the mapping, the grid, the street names, what lies beneath and before, the resonance of a collective noun.

Other works investigate the ecological changes since settlement: Grassland(scapes), The Elements: Dustbowl, thirsty work + white hot sun and Signs of decline, diverging paths + unstable hazard. Detailed stitching is combined with found objects and recycled imagery – kitsch long-stitch embroideries, a light shade styled as a flame, a hand-towel, bunting. I am reminded of the Daoist motto “surprise and subtle instruction might come forth from the Useless”.

The unifying force in Waters’ art practice is the absorption of process into an overarching strategy or vision. Waters’ exquisite making, the arduousness of process, creates time for contemplation – to tease out and reinterpret the complex tangles of myths, emotions and memories that find legacy in objects, across generations – in an interweaving of historic narratives with everyday life.

The language of Ghostscapes is remnants; remnants of fabric, objects, stories and lives that interrogate the archive and provide a home for ghosts to dwell. The mat at the exit reads WE CAME. As Waters’ writes “we came, welcome or not” and the cycle continues: YOU ARE HERE.