While Heide I features the in-depth exhibition of Mike Brown’s oeuvre titled The Sometimes Chaotic World of Mike Brown it was - at the start – coincidental that five other galleries across Melbourne would simultaneously hold the small festival titled Like Mike – what curator Geoff Newton calls a ‘‘celebration of an artist’s artist’’. Inspired by Richard Haese’s 2011 book Permanent Revolution: Mike Brown and the Australian Avant Garde 1953-1997, Newton considered a series of exhibitions featuring works by a cross-generational selection of contemporary artists whose works or studio practices were “Like Mike’s”. On calling Charles Nodrum, who from the 1980s had exhibited (and still exhibits) Brown’s work, he discovered that Nodrum had programmed an exhibition of Brown’s work in June. But at this stage neither knew that Sue Cramer was curating the Heide show based on their archives.

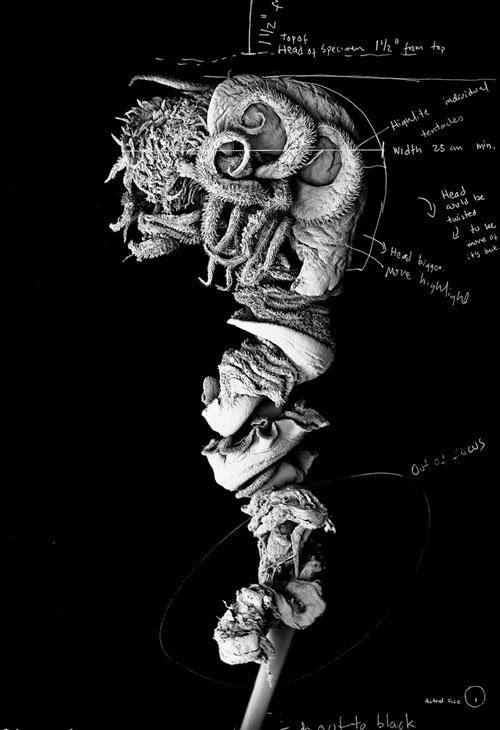

The variety of material on exhibit at Heide gives a pretty comprehensive insight into the vastness of Mike Brown’s oeuvre, life and ideas. Installed in various ways and places throughout the house museum we move through his early urban realist paintings and embroideries to painted objects – including his mid-century fridge with improvised handle, abstract ‘‘mindscapes’’, Pop-inspired text paintings about life, love and politics – like The Miracle of Love (1990) and Power to the People (1995), and his collages, assemblages and experimental films. A range of documentary material includes objects and articles from his Annandale Imitation Realist days, his graffiti and mural exploits and the scandal around his work Mary Lou as Miss Universe (1963). There is also archival material such as printed posters, invitations and catalogues Brown designed, some with texts propounding his semi-manifestoes – or what John Nixon refers to as “diatribes” – on art.

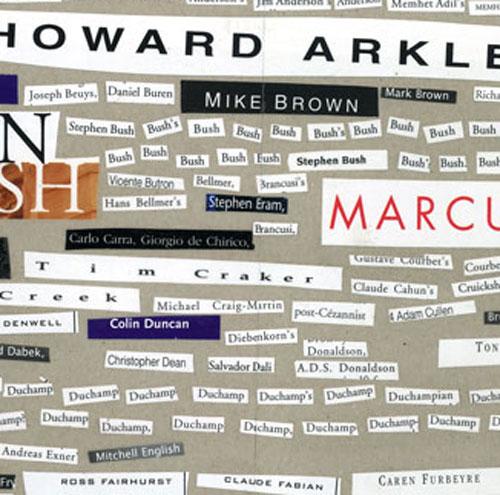

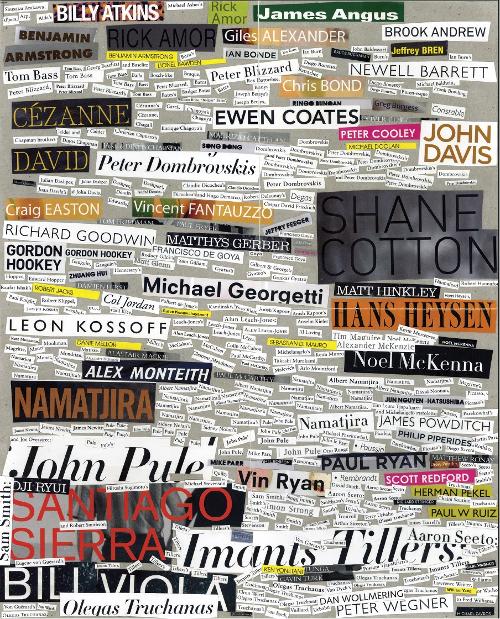

Overall, the Heide exhibition provides substantial backing to the proposition in Haese’s book: that Brown’s radical, uncompromising and expansive practice laid the groundwork for an Australian postmodernism. And this is where Newton’s Like Mike picks up and runs, exploring a range of practices either influenced by Brown’s oeuvre, or – with some artists not knowing, or liking, Brown’s work – pointing to similarities. So he curated the works of thirty-eight artists into five gallery exhibitions, each thematically linking to different aspects of Brown’s oeuvre.

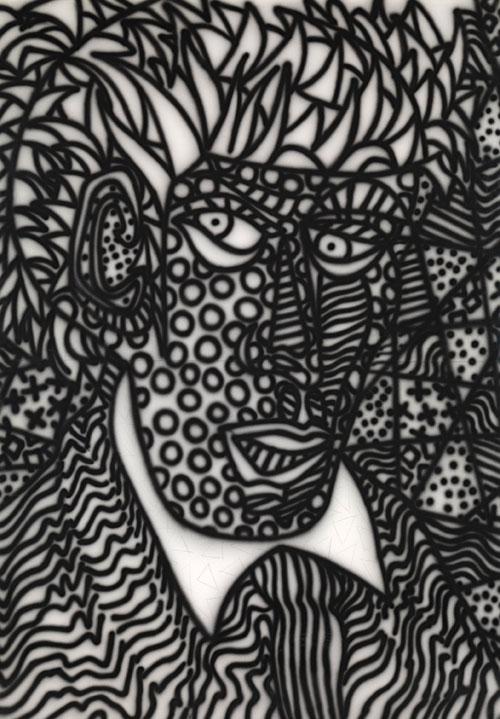

Charles Nodrum’s downstairs exhibition of Brown’s work focuses on pattern and portraiture but it also includes pornographic collages from Nodrum’s 1987 Hard Fast & Deep exhibition. Works in the upstairs Like Mike exhibition – titled Bloop or Hypertension can be fun – comprise sophisticated, postmodern extrapolations of what is featured downstairs. Damiano Bertoli’s beguiling Continuous Moment collages contain his typical twist on modernism explored through desire and Guy Benfield’s moving image collages turn signs of excess and consumerism into a melange of bad-Pop.

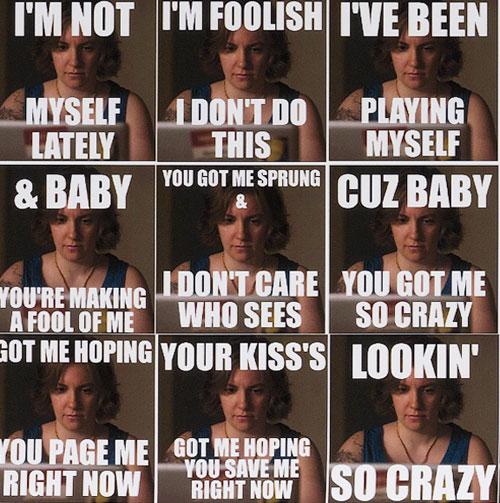

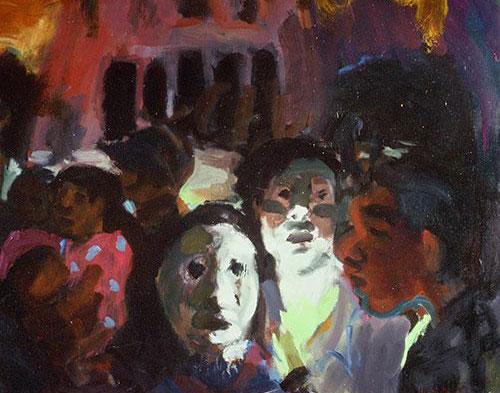

The four artists in Sarah Scout Presents – including Brown’s peers Pat and Richard Larter – focus on the human body. The pairs of legs in Claire Lamb’s Sisterhood (2013) and They all swing together (2013) give a humorous postmodern twist to Andy Warholesque voyeuristic and consumerist object d’art. Bryan Spiers’ and Julia Gorman’s works at Utopian Slumps’ materially downplay but activate Brown’s abstraction and installation; Gorman’s coloured paper scraps in Moroccan Style Wall Drawing in Pink (2013) burst up the walls and across the ceiling while Spiers’ highly coloured giclee print She’s lost control (2013) is a scan of assorted scraps and everyday items aesthetically arranged on a glass bed. Neon Parc’s all-female practitioner exhibition is installed salon-style, almost all on one wall, and features intimate, lo-fi works that range from posters and found-material collages to colourful ’’scribbles’’, the strongest ‘‘spin-off’’ from Brown’s work being the Kingpins’ hyper-Pop Night Dust (2005).

Last but by no means least, Linden’s Like Mike: Now What?? comprises installation and collaborative practices that are clever, striking and humorous. Extrapolating from Brown’s use of print media, Nick and Alex Selenitsch’s Slow Response (2013) fills two walls of Gallery 4 with large squares of coloured QR codes that ping our phones to various internet sites. And a very prominent postmodern extrapolation is Paul Yore’s Everything is Fucked (2013) – an enormous colourful installation completely covered in signs of spectacle and consumer excess.

The coincidental concurrence of the well-curated Heide exhibition and the Like Mike festival provides in-depth material and insight for exploring Mike Brown’s prolific and uncompromising oeuvre and the similarities of practices by generations of artists. Whether Brown provided the groundwork for an Australian postmodernism can now be fully explored and debated, and will be for years to come.