John Berger, in his 1977 essay 'Why look at animals?', argued that the close relationship between human beings and nature collapsed during the modern consumer age when our association with animals, once at the centre of our existence, became marginalised or reduced to spectacle. Any meaningful connection we have with animals and hence nature, he contended, was now predominantly through images where "the aesthetic moment offers hope".

Berger’s argument simplified an ancient, complex relationship that continues to this day. Animals have traditionally provided us with food, clothing, labour, sport and companionship; they are used in pet therapy and detection work; they are exhibited in agricultural shows, competitions and zoos; their images feature on television and YouTube, and in art galleries. Our interconnection is also illustrated in frightening ways, through exposés of the live meat trade to Indonesia and the Middle East, puppy farms, vivisection or, in the form of emergent and alarming diseases such as Hendra virus, where a deadly relationship between animal and human is revealed.

Animal/Human at UQ Art Museum elaborates on this enduring and contemporary relationship. From depicting animals as companion, specimen, trophy, pest or endangered species, or alternatively as anthropomorphic or metaphoric tropes, the artworks in the exhibition situate us, on the whole, as dominant in the relationship. It is because of our human needs that some domestic animals are valued to the extent that they become part of our family, and at the same time other domestic animals are bred for slaughter (often to feed our pets), genetically modified, experimented upon or shipped off in container vessels.

Through the curator Michele Helmrich’s selection of artworks, Animal/Human articulates the ambivalence or hypocrisy with which we treat animals, where some animals are treated more preferentially than others. One of the main themes to emerge is the joy of simply looking at an animal, recording its magnificent beauty, playfulness, heroism or its peculiarity, as Petrina Hicks’ portrait of the hairless cat Sphynx demonstrates. Adam Cullen, in his expressive, mock-heroic horse portrait Brumby, suggests the introduced wild horse to be a metaphor for the ‘fighting Irish’ and a play on his name, as brumbies are often ‘culled’. Conversely Ryan Presley’s The Cruxes compares the introduction of non-indigenous animal species with the impact of colonisation on Australia’s Indigenous peoples; his artist’s statement describes the habit of Indian Mynah birds of occupying other birds’ nests.

The animal as metaphor for the artist’s condition occurs in several works, notably in Lisa Adams’ Side-saddle where a comparison is made between the slowness of the tortoise and that of the artist’s painstaking work. In Kangaroo Point Gordon Hookey’s anthropomorphic kangaroo is depicted on a soapbox overlooking an anonymous cityscape. The kangaroo holds a rifle, and his glasses - along with his enlarged testicles – are painted in the colours of the Aboriginal flag so he “sees things the Murri way”.

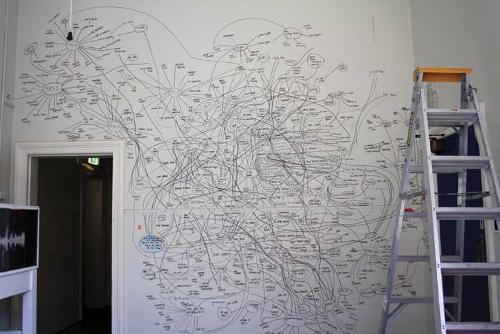

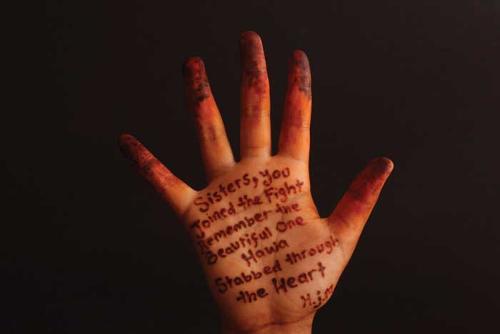

The violent physicality that underscores our relationship with animals is explored by both Pat Hoffie and Julie Fragar. They each address the hunter and the hunted: Hoffie’s installation comprises cardboard animal targets that have been shot-through to reveal embroidered domestic scenes, combined with images of refugees and performing animals, and Fragar has painted a luscious portrait of a hunter with his kill. In these works the artists expose our ambivalence towards animals: how we can be simultaneously compassionate and unemotional. Perhaps Lyndell Brown and Charles Green provide part of the answer in their work that features a Darwinian taxonomic tree (which was once crowned with the figure of a man) superimposed over a sea of people. Not another animal can be seen. Janet Laurence and Fiona Hall take the proposition further, pointing to the negative impact of human intervention on species that are now either extinct or endangered.

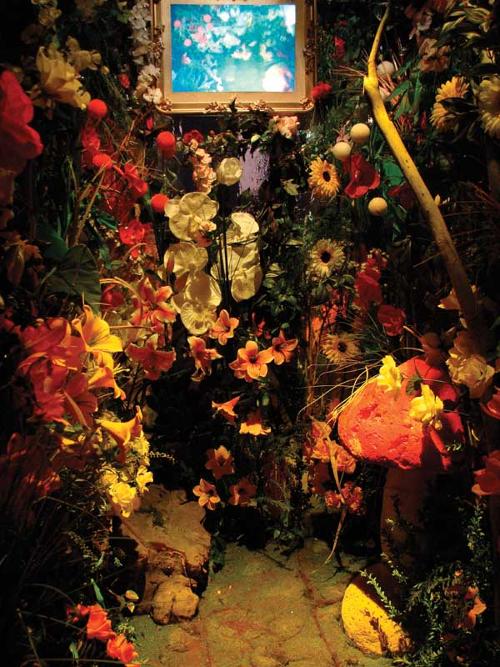

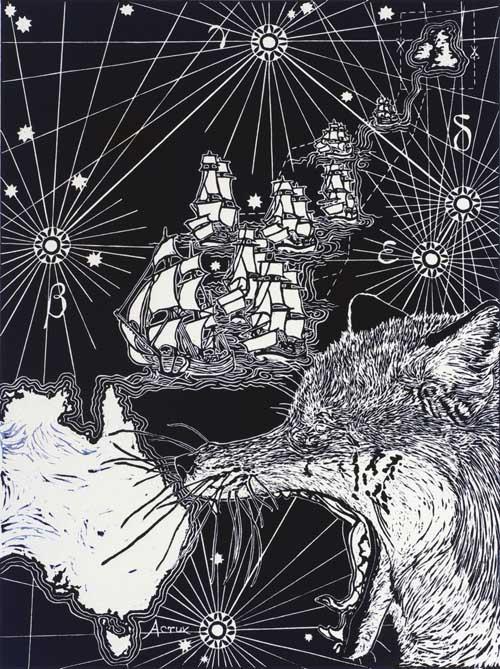

The exhibition’s most compelling and positive artworks are those in which the relationship between animal and human is most intimate, where there is almost no ‘relationship’, but a mutual dependence or co-existence that simply ‘is’. David Chesworth and Sonia Leber’s video installation The way you move me reflects on the intimate relationship between a farmer, the land and the wild and domestic animals thereon. The balletic manoeuvres between working dogs, cattle, farmer and sheep reveal a relationship that is mutually dependent, economic and elegant. In Zugubal, Alick Tipoti’s ancestral beings are represented in a meticulous linocut print. For Tipoti, land and sea creatures, artefacts and ancestral spirit beings are all interconnected, interwoven into the sky, sea and the Torres Strait Islands. For Tipoti, Berger’s claims of disassociation with animals would make no sense, for his spirit beings are both animal and human and, very firmly, a part of him.