All our relations explores the nature of connection between people - what defines these connections is left up to the visitors who engage with this exhibition. As such the 18th Biennale of Sydney proves to be a profoundly individual experience in direct opposition to the curatorial themes it proposes.

The most successful exploration is not by meta-narratives or universals but by life's experiences The MCA arm is the most seamless example of curating the themes of the Biennale. It is aesthetically intelligent, engaging and an enjoyable experience of the art within context. This thematic introduction has two lasting impressions for all the sites: the first being that many of the works are pale or neutral, even to the extent of being white in hue. Perhaps paleness better allows contemplation for how we connect emotively to each other and the world around us. Or maybe it ties in with the non-confrontational nature of the theme; the second being the return of the hand of the artist. Highlights are Liu Zhouquan’s large installation of bottles that have been painstakingly handpainted on the internal surface. Similarly, Park Young-Sook’s white porcelain jars revisit a traditional craft technique; as does Yeesookyung whose large singular sculpture is comprised of ceramic shards reassembled for Translate the Moon. Zoe Keramea’s folded paper moths, which adroitly sit anywhere comfortable within the exhibition space also remind us that the art is being made by humans with a human experience embedded in the work.

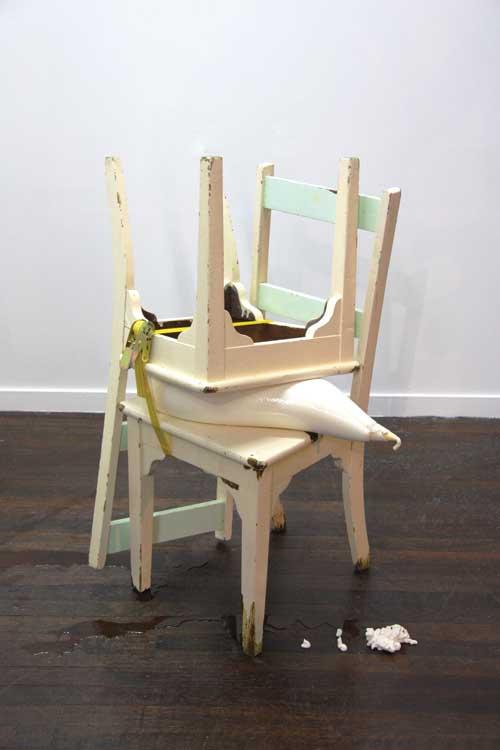

A kitchen table aesthetic of handicrafts dominates all the sites. It is the intimacy of domestic crafts that offer audience inclusion. Ceramics, glass, papermaking, paper-folding, feathers and sewing are all very feminine arenas in a traditional sense. Both the domestic arena and its necessity for collaboration is reconstructed within Erin Manning’s Fold to Infinity, whereby the installation contains a table for visitors to contribute to the sewing circle. It is the kitchen table assemblage and the authentic expression of this that creates the most genuine interaction within the show in its entirety.

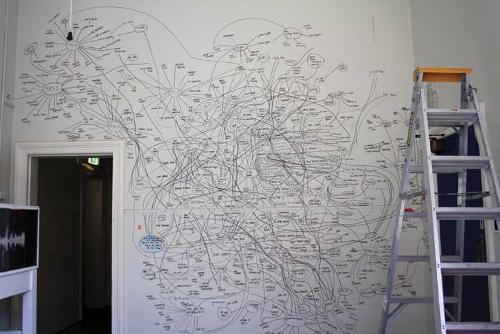

Materials and techniques are cleverly interwoven with the curatorial themes throughout the exhibition over all its sites to remind us of the human element of art. Further exemplifying this point are the many community collaborations and the necessity of audience participation to complete the process of the art creating an authentic experience for the viewer. Cleverly the curators have chosen works that comprise community collaborations such as Monika Grzymala’s The River, utilising handmade paper by the Euraba Paper Company (Grzymala even credits her work as a collective). Cleverer still is the inclusion of works which will evolve and continue the dialogue after the end of the exhibition, such as Tiffany Singh’s Knock on the Sky Listen to the Sound at Pier 2/3 which invites members of the public to take a chime home, decorate them and return them to any location they choose on Cockatoo Island. Thereby the viewer also becomes a curator.

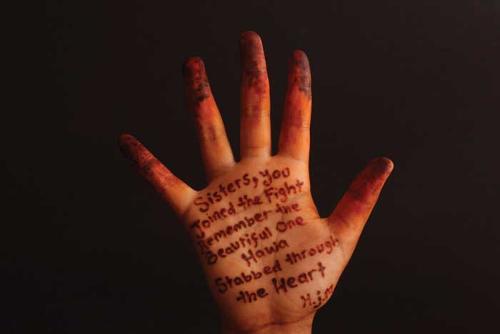

Other works will only be created within the context of the Biennale and rely on the audience participating to make the art work. Nadia Myre’s The Scar Project (found on Cockatoo Island) is one such poignant work that allows space for the direct expression of audience experience. Upon talking with the artist she succinctly explained that she invites visitors to the exhibition to "sew their own scar". Whether you choose to sit down and confront the canvas (truly a metaphor for past experiences) or walk away, the collaborative project resonates: what are the scars of our lives, surgical or emotional? Time and reflection may be a passive interaction but a lasting one.

It’s a brave step as the curators are asking for the experience to dictate the process having relinquished control of the outcome. But this is how the curators approached the entire Biennale which proves to be so refreshing and unique. They started as a collaborative duo and allowed the themes of contemporary art to emerge rather than force a predetermined idea. This is the greatest achievement of all our relations as it is not alienating, confronting nor an assault on the senses. It is refreshing to feel that as an audience we are invited into the show, thematically and as contributors.

The subtler the aptitude for human understanding, the more poignant the art becomes within the exhibition. In fact, the artworks which explore global issues such as the environment or war disasters are less satisfying; however they create a necessary discord by reinforcing the aesthetic emotional intelligence of the rest of the show by being less didactic. The shift to global politics proves to be jarring against the inviting nature of most artworks that fall outside these two frameworks.

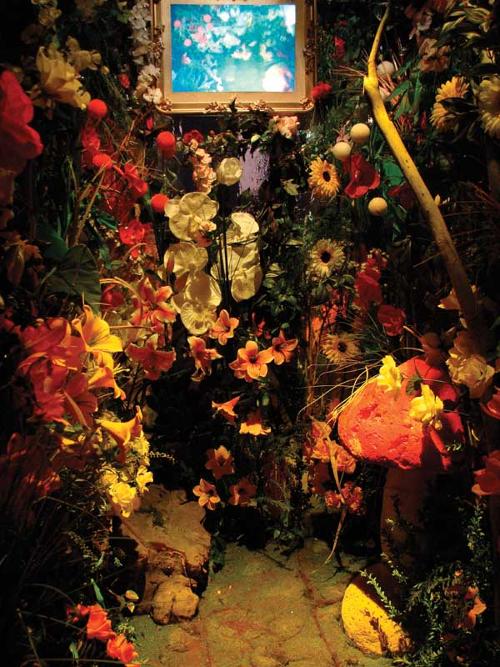

A number of works cause the viewer to have an individual experience but their gentle manipulation of our access points mean we experience them as a collective, such as Ed Pien with Tanya Tagaft’s Corridor of Rain installation. Within the confines of the installation viewers must walk solo for fear of damaging the delicate paper that encloses. Once reaching the centre we are invited to look through viewfinders: the experience is shared but individual at the same time.

The extensive use of fugitive materials further enhances the transience of the collective experience. It would be easy to relate the presence of so many non- permanent materials with the transitory nature of experience. An in-depth phenomenological reading of this exhibition would not be without its rewards.

Catherine de Zegher claims that the exhibition “concerns a global movement of art and thought that has been under the radar and now emerges as radical and dynamic, bringing forward a significant change...” Whether the art is radical or dynamic is highly questionable: being quieting and meditative in relation to past Biennales is about the most radical thing about this exhibition. “…bringing about a significant change” is simply a leap of faith of “time will tell” for the many people who may visit this exhibition. Will we be a new society globally after interacting with the art of this exhibition? Perhaps, if the aim of the exhibition is to relax and recognise things about ourselves and those around us. This could be the principal strength of the curatorial theme: it reassures rather than confronts. Art rather than being the recognition of the Other and expressing a de-centred subjectivity is returned to the realms of inclusion and communion. More agreeable in de Zegher’s statement is that the exhibition connects “the most intimate meanings of place and time…”.

The connectedness and exchange of the authenticity of the artists and the audience’s interaction is what is resonating about the human condition. This exhibition is a relief as it is not emotionally delinquent like past Biennales, it certainly doesn’t rely on the 'wow!’ factor. The curators have made an honest attempt at exploring truthfulness through the situational realities of others to exemplify that which make us human.

Lizzy Marshall