Despite its title, Bad Angle is a good-looking show. Comprising accomplished photography and new media, the show revels in a lesser-known meaning of that phrase — its use amongst magicians to describe the angle from which the audience can perceive the sleight-of-hand or other means that effects the trick. These artists are interested in perception, in angles of incident and reflection, and eschew photography and film’s documentary qualities except when they act as evidence of mysterious happenings. The title resonates as many of the artists step beyond the frame to shape the experience of the work through external elements. This interest is shared by the curator, Clare Lewis, whose placement of works maintains a sense of aesthetic and psychological drama throughout the exhibition space.

One of the most rewarding works is Rachel Scott’s Half Square/Half Crazy (after DG) (2009). The artist moves mirrors around a static camera, to achieve different fields of vision, including behind the camera. The imagery and sound are subtle — the lint on the floor from the breeze of movement, the pad and squeak of sneakers on polished concrete — but the mood is heightened by a film noir soundtrack so that this apparently simple formal exercise becomes an exploration of the psychological dimensions of perception. Scott’s meditative Moving through time (whilst standing still) (2001/2009) focuses on a window frame as it revolves above the city below.

Jess Olivieri & Hayley Forward with the Parachutes for Ladies present a number of images of unexplained action. In “I thought a musical was being made” Part 2 #1 (2009), the initial drama of the choreographed flower formation of a chorus distracts from their amateurishness, revealed in part by the way the T-shirts of their makeshift costumes are too short to cover the gussets of some participants’ pantihose. In the intriguing series Parachutes for Ladies #1- 4 (2008 – 2011), pedestrians are captured in group actions — leaping in the air, a bowed huddle on a street corner. A related video doesn’t deliver an explanation but instead may be viewed through a kaleidoscope that renders it soporifically beautiful and utterly impenetrable.

Clare Milledge’s elegant photos of constructed ritual are uncomfortable: whose ceremony is she using? in what spirit is she undertaking this enquiry? The props — a suit with kangaroo head-dress, a whip, sweeps of flour — risk farce and ridicule of the practices she is exploring. This is most delicate in Purifying Dance (2011), where her movement seems to echo Aboriginal ceremonial dancing within a circle of flour that evokes desert sand. Along a very fine line, Milledge treads the side of solemnity. She might not be a believer in these invented rituals or their real life inspiration, but this doesn’t feel like deadpan cultural mischief.

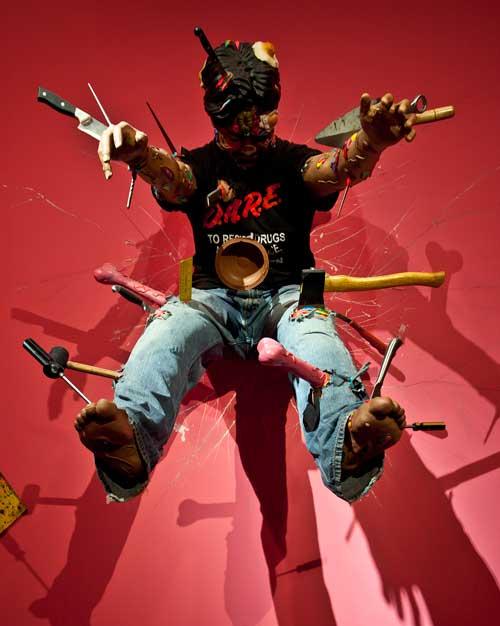

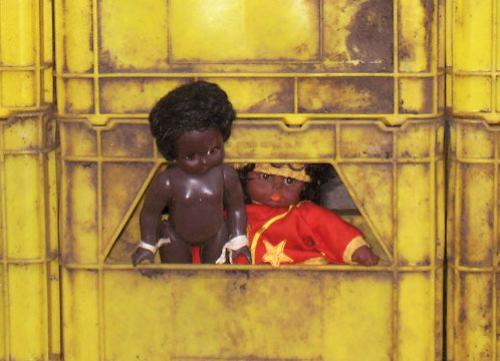

The artist’s The Last Visible Dog (2009) is a two minute looped new media work that takes the viewer through jerky eerie journeys that tunnel through ruins to find a slender naked beauty, face obscured by an elaborate headdress. The imagery reaches to the viewer over black glass floor panels, much like moonlight over water. Also elaborately constructed are Shaun Rafferty’s scaled down cardboard drive-in, and the grown worlds of Jamie North’s photographs. Here native seedlings on a bedrock of sharded ceramics are a metaphor for reclamation of territory; the fruit fallen among them evidence of an out-of-frame mature survivor. Far beyond quirky, Heath Franco’s Your Door (2011) is bemusing madcap non-sense. Revelling in long surpassed special effects, bizarre costumes and repeated statements, the work is equally unsparing of the dignity of the artist and of the viewer’s nerves.

Even as the artists are concerned to evoke rather than explain, the nature of photography and film means that the works must encounter reality or reason, and it is precisely this tension that makes the exhibition so interesting. Garry Trinh’s images wouldn’t be poetic if his urban and suburban scenes were not transformed by phenomenological forms of natural light. Ben Cauchi’s works wouldn’t generate a sense of magic and nostalgia without their invocation of early photographic technique and the superstitions of that time. Milledge’s ritual works wouldn’t be confronting or Franco’s surreal except for their enactments. Similarly, our curiosity wouldn’t be as piqued by Olivieri and Forward’s work if they were painted. Despite the clear fabrication of a number of works and the fantasy of others, in each case, something actually happened. The pleasure of this exhibition is in the unresolved guesswork of what this was.