With so many international biennales around the world showcasing the work of so (comparatively) few artists the theme of each of these exhibitions becomes a crucial means through which familiar processes and platforms might be reconsidered. The other aspect that might make it worth travelling to these globalised and potentially globalising events (when you know that you’re probably going to see mostly same-same but different) is the way in which a particular context changes the work. When considered judiciously as an important part of the curatorial brief, exhibitions can offer the possibility of reappraisals of familiar work and commonly held values, and also pathways through which to think about new relationships and connections.

The theme for the third Biennale of Singapore (SB2011) — Open House — was conceived by its Artistic Director Matthew Ngui and curators Russell Storer and Trevor Smith as “an invitation” to visitors to examine “the often fiercely guarded boundaries between public and private, and the manner in which differences may be bridged through interaction and exchange”.

In economic terms, the processes of interaction and exchange could be described as the very loins from which the present Republic of Singapore originally sprung; and now, within a short history of almost fifty years, (independence from the British was gained in 1968 and from Malaysia two years later) the republic seems keen to establish its own cultural identity. This Biennale is an investment in that stake. The theme Open House, according to Ngui, draws inspiration from the local practices of opening up the living spaces of various aspects of the culturally diverse Singaporean society to visitors during religious festivities that include the Chinese New Year, and the Hari Raya and Deepavali celebrations of the Indian communities that live side by side with native Malaysians, European expats and a range of other cultural groupings in the capital of the tiny 41.8 kilometre long island. With a total population of approximately five million, tolerance is essential. It’s also essential as a means of preserving Singapore’s status as the fourth largest financial centre in the world — a position that would be impossible without the vast and brisk trade of exports and imports much of which comes via a harbour that is one of the five busiest ports in the world. The skyline changes by the week — building continues in spite of the global economic crisis, and architectural competitiveness makes for an archiscape that is at times breathtaking. For all this to happen it is important that all doors appear, at all times, to be open. Economic growth depends on it. Even though the pointy-end of decision-making, about what is and is not permissible, may still be decided behind more-or-less closed doors.

The theme of ‘open house’ was underscored by the Biennale’s annexation of what was Singapore’s first civil airport as one of its four major venues. Opened in 1937, Kallang also served as a military airbase during WWII and later as headquarters for a government organisation that had promoted “social cohesion and active citizenry”. The Singapore government’s insistence on maintaining a façade of social cohesion at often high costs to individuals and groups who may have been critical was pointed out in Geoffrey Robertson’s 1998 publication The Justice Game.

.jpg)

Since then things have changed somewhat; even so, a controlled and controlling politeness characterised much of the overall ambience of the opening days of the exhibition. Within such a context, the most successful voices of dissent came in world-weary laconic jabs: Elmgreen & Dragset’s installation languished in the vast hangar space of the airport like left-over contraband from a proto-colonial nightmare. A big mock-Tudor barn, the interior piled with hay and arranged with Bavarian trinkets, provided the panto-scene for a bevy of bare-chested, lederhosen-clad boys, languishing dreamily amidst the hay bales as they perused their mock-manuals. All this in a city where homosexuality is still illegal. In this work the capacity of an international biennale to sanction the full-blown cultural tackiness of another nation was celebrated to its full theatrical hilt, with curtseys to art history (Rauschenberg) as well as to cultural diplomacy.

The baroque excesses of cross-cultural mistranslation were also celebrated in Ming Wong’s remake of Pasolini’s iconic film Teorema. Re-shot in Naples with the artist playing all five principal characters, the five screen video work featured the artist in a range of dated and daggily appealing outfits and wigs. For Australian members of the audience, echoes of Chris Lilley were not too far away; in spite of the almost slapstick hilarity of some of the takes, a self-conscious poignancy threaded through the efforts of a young Asian man committed to producing approximations of the Italian classic set in Italy.

The artist’s whole-hearted embrace of the awkward adaptations that are part of cross-cultural interpretations, together with the camped up charm of the piece, rescued it from even the merest hint of sentiment. The same could not be said about Phil Collins’ perfectly produced, self-consciously beautiful film documenting the adoption of skin-head culture by artfully posed groupings of Malaysian youths. Whether posed and pouting in staged street scenarios, or assembled reverently in gorgeous temple-like interiors filled with clouds of tropical butterflies (!?) the mise-en-scène exuded the saccharine sweet artfulness laced through with expense and privilege that has come to characterise so many acclaimed biennale ‘art films’ lately.

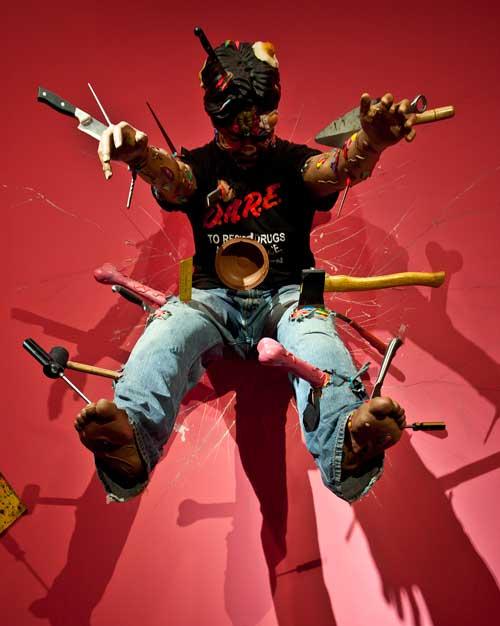

Perhaps the transformative triumph of local interpretations on globalised cultural influences was more eloquently (and hilariously) expressed in Louie Cordero’s My We, an installation featuring a range of schlocky figurative sculptures in various stages of death-throes resulting from having been punctured by a range of unlikely artefacts. Kitschy paintings lined the room that included a garishly decorated videoke machine featuring a loop of local Filipinos from barrios across a range of provinces having a go at Frank Sinatra’s My Way. Recent legends tell of a spate of attacks on local performers right across the Philippines who didn’t get the rendition ‘right’; apparently their way was not the right way in the minds of the attackers. Here, it seems, local inflection wins out. Funny, sad, irreverent and a paean to the irrepressible persistence of the provincial, Cordero’s ‘take’ on global hegemony and totalising cultural imperatives is based on “a brew of love for the underdog and masochistic self-loathing” (Isabel Ching, catalogue essay).

For many of the nine Singapore-based artists included in the biennale a bedrock of local legends are still being sought. Charles Lim’s video All Lines Flow Out takes viewers deep beneath the foundations of the towering skyline and into the network of underground tunnels and canals that criss-cross the foundations of the city. In these invisible and uncharted tributaries, Lim suggests a fecund lymphatic system that is far more complex and evocative than the surface forms that have their roots deep in its being.

To the outside world, the city-state of Singapore projects a façade of orderly compression — a smooth functioning, rational exterior that runs on the labour input of the foreign workers who make up the major proportion of its workforce. The fact that half of the sixty artworks were new or commissioned, together with the fact that nine of the artists were local, enhanced the exhibition’s potential to suggest a range of other ways of imagining the locale. Spectres of the past and fleeting visions of the uncanny flitted through a number of works, as did the tendency for the reappearance of mythical creatures more usually associated with other realms. Godzilla appeared as a cameo appearance in a number of works.

But it was another exhibition, run simultaneously at the National University of Singapore Museum, which provided a broader and deeper context from which to consider contemporary work in the Biennale. Much of the intelligence and magic of Ahmad Mashadi and Shabbir Hussein Mustafa’s Camping and Tramping Through the Colonial Archive: The Museum in Malaya came from a critical juxtaposition of a diverse number of objects from a range of historical periods. The exhibition format challenged the very taxonomies that separate rational from ‘non-rational’, art from artefact, and science from magic. Working like artists, the curators retrieved facts and data and details from cleavages that run under and between the idea of an ordered, ‘progressive civilisation’ that was used to establish Singapore as a nation. There was plenty of evidence of the kind of illegitimate, disqualified areas of experimentation and knowledge that run counter to the idea of polite, rational, classifiable cultural practices. All of which filled its rooms with the kind of irreverent, contradictory and speculatively rich tributaries of possibilities that often no longer flow so readily within the ecosystems of biennales.