Completed under CAST’s ongoing Curatorial Mentorship program, Out of Site is an exhibition that presents six diverse Tasmanian artists’ musings on various sites of incarceration and control in colonial Van Diemen’s Land and their ongoing social and cultural legacy.

Upon entry I hear a combined soundtrack of breathing, sighing, scrubbing and the dense rumble of some unknown natural force. Tracey Cockburn’s black box frames reveal deep set metal plates with various layers mechanically printed on each surface. The stroke of the printer and the tessellated edges of some forms increase in detail upon my approach to show a view of an imagined free blue sky imprinted with the residual afterimage you see when you blink your eyes. A barely cogent symbol from a distant mental realm imprisoned in perfect black rectangles.

Four large dense works on paper and mdf evoke rust, stains, scars and the weight of time. This collaborative work by Sarah Maher and sound artist Nigel Farley pairs these large formally hung works with a foreboding atmospheric sound-scape of subtlety and depth. The four panels are accented by a slightly smaller work, a burst of yellow with a bleeding side hung higher than the others in a playful peripheral leap. This accumulation suggests a deep and multi-dimensional melancholy.

Brady Denehey continues the cells and rectangles form with his four square digital photographic works. The images have four different overall tints that hint at the troubled colours of institutional buildings — a blue-gray, a pinkish fog, a dark navy and a deep emerald. The images are fantastic, in the most literal sense of the word — a careening clipper in troubled waters; a singular martyr on a beach in a mirage; a streak of blood towards a distant horizon.

The triptych by Elizabeth Lada Gray of large box-framed assemblages presents an overhead, floor-plan style view of various buildings. The floor plan has no doors, each space is contained and forever sealed. The work uses a faux-antique style of paper ageing, staining and blotting to carry a swathe of record, myth, memory and pain. It suggests the subtle and overall interweaving of institutional systems of incarceration and control.

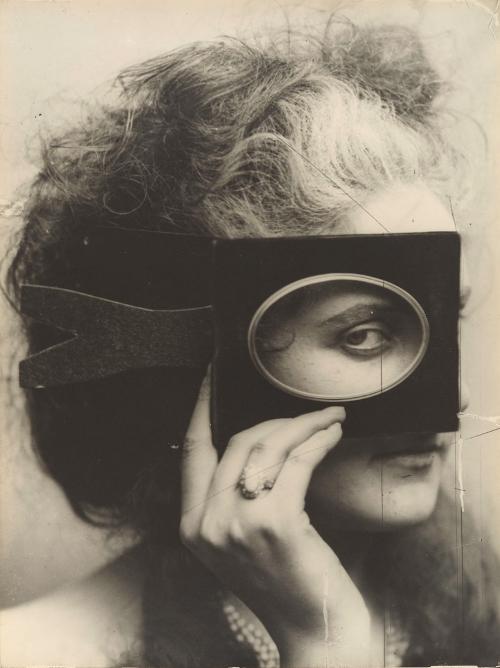

At the end of the rectangular gallery in a narrow corridor the width of a solitary confinement cell, we find the work of Alyssa Simone. A diminutive projection of a portion of a sandstone wall is accompanied by a soundtrack of female breathing, the breaths are successively deeper and culminate in a deep sigh. Out of the black and white video, a glow permeates the mortar of the solid wall turning it liquid. At the peak of the breath, the glow morphs into a spinning vortex of welcoming light. The repeated, meditative focus suggested by the short loop cycle of the work contributes a mantra-like quality.

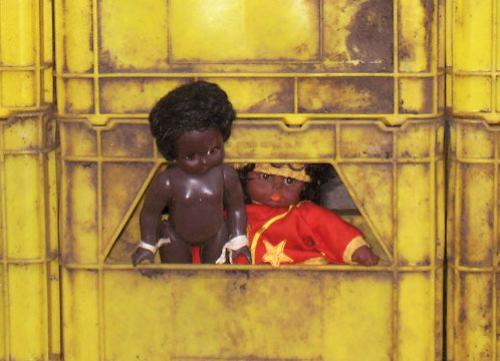

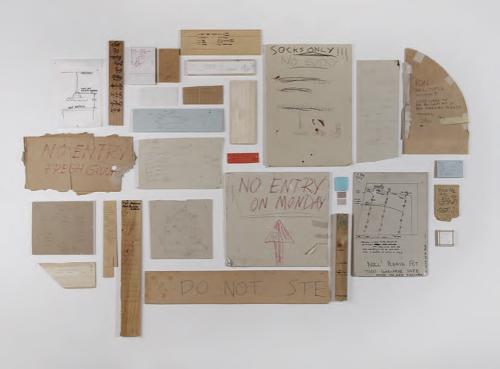

In the largest cell in the space is the work of Shaun McGowan. A giant Tasmanian map made of plaster cast heads, dolls and action men. Meticulously patterned painted fence-posts float in front. A clay mask with like-like eyebrows extends a phallus-tongue on which B1 and B2 dance. A scarred and oily trunk houses a collection of found, handmade bananas in pyjamas — each with their differing ages and deformities — crammed uniformly inside. No means of escape.

The Curatorial Mentorship encourages complexity and risk-taking and Needham approaches it in this way. The show comes from a long and sincere fascination with what she calls the psychological residue of sites of incarceration. These sprawling institutional relics are somehow at once occupied and empty, intact and decrepit, growing and rotting.

In addition to the well-trodden Tasmanian historical response frame of the exhibition, the wordplay suggested in the title unlocks another gambit. Needham suggests that these are site-specific works designed in some ways to occupy spaces at one or many of the sites they portray. She suggests that the denial of the works, as part of the curator’s strategy, to occupy actual historical sites of Tasmania’s institutional past is symbolic of the displacement and denial of the rights of the incarcerated.