.jpg)

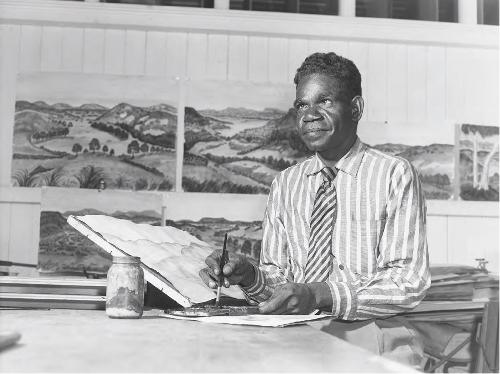

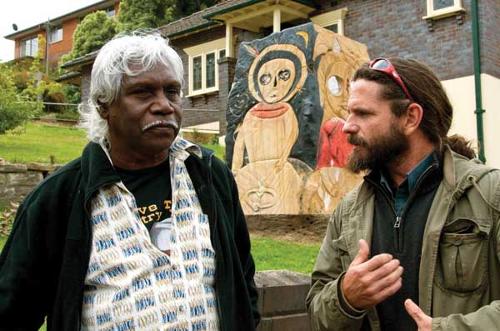

Alice Springs-based artist Billy Benn, winner of The Alice Prize in 2006, is known for saying that he would paint every hill in his country and when he had finished painting them all he would stop and go back there.

This dream of return came true after Benn confided in Arts Coordinator Catherine Peattie his desire for a book on his work like the 2002 book on Albert Namatjira by Alison French that previous Coordinator Neridah Stockley brought into the Bindi workshop in Alice Springs and which has been much thumbed and admired. Billy Benn did get to go back to his country, his father's and his mother’s country. He mostly paints his father’s country of Mount Swann and his own country Harts Range but it doesn’t seem likely that he will stop painting.

A committed and obsessive painter Benn began working on offcuts of wood in the corner of the Bindi workshop (a cross cultural organisation providing opportunities for all people with disabilities for over 32 years) where he was employed to make metal tucker boxes. The long horizontal shapes of the pieces of wood suited the sweep of his panoramic landscapes and the fluorescent paints he occasionally used made his hills luminous.

In his youth Benn once met Albert Namatjira with his "flash shirt, good hat and big truck" out in country painting. Ngukurr painter Ginger Riley also met Namatjira and was inspired by him. A memory like that, an Aboriginal man out in the landscape painting on paper with brushes, lasted a long time for both Benn and Riley until they each became artists, not School of Namatjira but After Namatjira. In her essay on Billy Benn’s work Judith Ryan writes about the way both Benn and Riley were inspired by Namatjira. She also draws attention to affinities in Benn’s work to the art of J.M.W.Turner and his clouds of elemental colour and space; Colin McCahon and his vision of painting as needing to be raw in order to communicate a vision of the land; and Paul Cézanne, another obsessive hill painter.

.jpg)

Ryan also quotes from 'Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth' (2008) a recent book by Australia’s most famous academic feminist writer Elizabeth Grosz. She connects with Australian Indigenous art to philosophise about all art: “All works of art share something in common, whatever else may distinguish different forms, genres and techniques from each other: they are all composed of blocks of materiality becoming sensation...Art is where intensities proliferate, where forces are expressed for their own sake, where sensation lives and experiments…”

'Billy Benn' is a wonderfully produced book which intersperses descriptions by Catherine Peattie of the three trips made by her, Benn and Benn’s close friend Ian McKinlay with images of artworks as well as her photos of the places they visited. The three travelled in helicopters, planes and by road to revisit hills and waterholes, ranges and bores. First they visited Benn’s mother’s country then his father’s country and finally rockholes in ravines. Benn’s own stories appear in Arrernte as well as in English.

The more than 100 colour plates are closely linked to the text so that when you are reading you are able to look at the work being discussed. This is essential in art books but rare. An index would have been good.

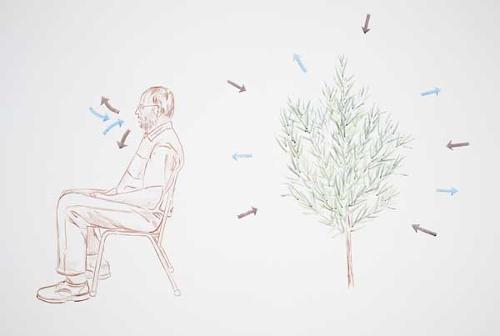

A real revelation in the book for me (a BiIly Benn fan) was finding out about his informal art apprenticeship to the Chinese wife of a mica miner. Benn worked in the mica mine and he learnt about Chinese calligraphy and brush painting, where the spirit in which a painting is made is as important as skill, learning or time. As set down by Xie He, an artist, writer, art historian and critic in 6th century China, the first principle of Chinese painting, without which no other principles are worth much, is spirit resonance, the nervous energy transmitted from the artist into the work. Billy Benn has got it.