The opening passages of Anna Banti's 1947 novel 'Artemisia' describe the author sitting in the Boboli Gardens staring down at Florence in flames as the German army retreats. Banti’s home has been destroyed by the bombings, as has the scholarly work that lay within, an unpublished monograph on the legendary seventeenth century artist Artemisia Gentileschi. But Artemisia, the flesh and blood woman that Banti has communed with all these years, is not so easily lost. Her voice asserts itself amid the despair and a dialogue between seventeenth century artist and twentieth century narrator ensues.

Artemisia emerges as a complex character - sensitive, diffident, sometimes playful – unwilling to yield to the author’s curiosity. Banti approaches her with trepidation and knows when to back off, lest she offend. In adopting such an approach the author of course acknowledges the impossibility of capturing with any degree of certainty the emotions of centuries past. But it is through the very fugitive nature of Artemisia, her nonchalant withholding of information that her voice emerges with an authentic quality.

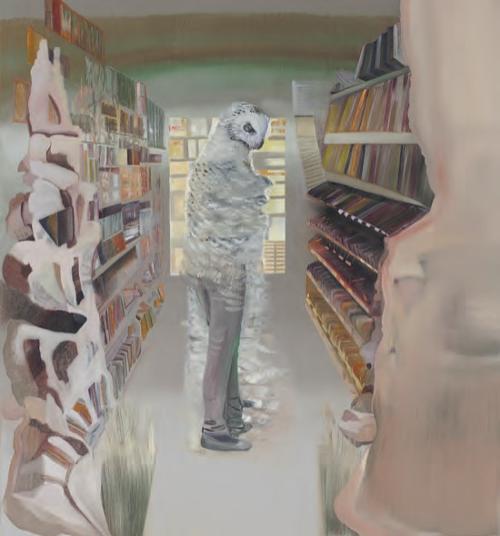

This seems a rather long-winded way to introduce the works of Angela Stewart but her incursions into history through the painting process seem so intimately related to the work of Banti, consumed as it is with trepidation and self-conscious doubt. The paintings presented in 'Unlacing Carnal Margins' (produced between 2007 and 2010) are based on a dialogue between herself and painters of the sixteenth century, most notably the greatest female artist of the Renaissance, Sofonisba Anguissola. Stewart skilfully manipulates portrait works by Sofonisba – in Poesis 1 a version of Anguissola’s 'Portrait of the Infanta Clara Eugenia' (1599) and in 'Poesis 2 the Portrait of Don Carlos' (c. 1560).

Sofonisba’s original portraits of Clara Eugenia and Don Carlos present the sitters through a strictly codified visual language, presenting their public faces which exclude all expression of emotional states. It is from these inscrutable characters (the decorous noblewoman, the imposing young ruler) that Stewart attempts to extract meaning, a deliberate folly it seems.

In transforming these images, Stewart denies herself the use of seductive colour but concentrates on varied surfaces, which range from quasi-translucent to impasto, creating a tension between the dissolution of form and the assertion of corporeal presence. The canvas is worked upon, scraped back and built up again, in an effort to uncover the 'pentimenti' or the traces of another artist’s hand, the errors of the past. Like Banti, Stewart’s approach is self-reflexive, a kind of heightened suspension of disbelief in which the object of her creation takes on a life of its own.

Contemporary women range around the edges and backgrounds of the portraits, though they never impinge on the main event, as if to suggest a contemporary eye on events, echoed in the gaze of the artist. Ultimately, Stewart’s work is a meditation on the creative process itself, the endless deliberations and anxieties associated with making art, and perhaps most particularly, questions of resolution in artistic practice. When does the artist relent and leave the surface be? The visceral and haunting quality of the works seem directly related to their implied lack of completion, the idea that they may be taken up again to emerge in an altered form. Viewing the works is an emotive and immersive experience as their ghostly figures are spotlit dramatically against a surrounding void.

For over twenty years Stewart has been negotiating vast chasms of time within her art practice. In previous bodies of work she has done this by inserting her own image into historical works of art. In this current series she steps outside the canvas, though her presence is nonetheless felt, a third character in an intimate and subtle negotiation.

The exhibition is just one of five impressive shows by graduating postgraduate students from the School of Design and Art at Curtin University.