.png)

'Possessions' is the title of a book published in 1999 by anthropologist Nicholas Thomas about indigenous art and colonial culture in Australia and New Zealand. It is a rich volume dipping in and out of the fertile territory of intersections between indigenous and non-indigenous cultures, their borrowing and lendings, and involving what he calls a 'productive blurring between anthropology and art history'. He concludes that:

"...identity is never a possession, never something people have, never framed by an entity such as a nation or a culture. It is rather a relation or a transaction."

Yet it is the issue of possession (who owns the art, the culture, the land, the imagery, its interpretation) that ricochets around current indigenous art and the explosion of publishing on it. As well as further blurring between art history and anthropology. Anthropologists authoritatively give us background information that we have to take at face value, some numb us with detail, others like Howard Morphy suggest often that there is less difference between cultures than we are led to believe. He seems to intimate that our gut feelings will take us far. Art historians also like to flatten us with regurgitated information but there are a few who connect ideas, art and artists and lead us towards new thoughts and fresh places.

The anomalous position of Aboriginal art, often full of graphic vitality, often seeming a bright decorative skin for nothing much, often involving an ecstasy in and of paint, often serious and profound, but in general flooding Australian art in overwhelmingly profuse quantities yet always ethnically defined and thus somehow outside Australian art, cries out for explanation even as it does not seem to need it.

Must it always be talked about separate from other art? Is this a kind of segregation? Is it helpful? The real issue to me is in some way whether Aboriginal art is seen to add something to the world, change it and contribute something new (though old) or whether it is simply another category of art commodity, another genre.

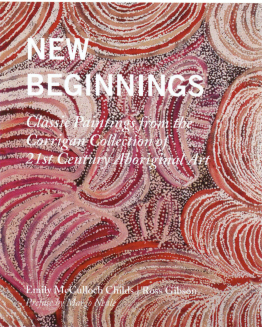

Art McCulloch and McCulloch, Fitzroy, Victoria, 2008. 159pp, RRP $79.95

Two recent books, 'Icons of the Desert' and 'New Beginnings', each in their titles setting themselves up as vital and fundamental, are based on two collections and each is the educational arm of these collections. We might wonder who benefits most from the publication of these books. If the collectors really care so desperately about the painters wouldn’t the money be better spent providing scholarships for Aboriginal children or helping their communities with bores and housing?

Collectors benefit from having the works they own appear in books, many sell the works off just after a book is published, many collect just for the joy of possession. How do we feel about Americans John and Barbara Wilkerson, who first saw Australian indigenous painting in 1994, having bought so many iconic Papunya boards anyway? Shouldn’t the boards be in Australia? Initially the Wilkersons collected American folk sculpture, then for fifteen years Aboriginal art and now they are onto outsider artists. Clearly they like the quest, the chase, learning about and ‘possessing’ the novelty and strangeness of ‘others’. Desire for ‘authenticity, originality…mystery…[and] spirituality’ drive them.

'Icons of the Desert' is very directed to an American audience and accompanies an exhibition touring America. It is a desirable book, with authoritative commentary by some of the usual writers on the topic, Vivien Johnson, Fred Myers, R.G. Kimber, Roger Benjamin and a preface by Hetti Perkins. Its production did however get knotted up in questions of permission and possession and thus it ends up in Australia with several blackened/censored pages of artworks that it was decided not to include in Australia though they can be seen in America.

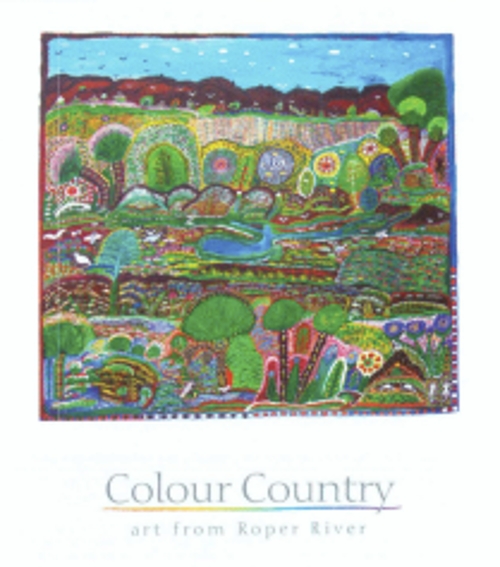

'New Beginnings: Classic Paintings from the Corrigan Collection of 21st Century Aboriginal Art' is more directed at an Australian audience and like Icons includes a story per painting per page though the images are bigger and the works are all recent. The rapturous cover image by Wingu Tingima is especially seductive, wrapping the book and the eye in spreading glowing arcs of soft pink, red and white. Essayist Ross Gibson links Zen and the idea of the ‘mind device’ to contemporary indigenous painting while Emily McCulloch Childs does the biographies and stories of a wide range of works. Possession of this book feels connected to food or digestion involving something as colourful as hard candy or liquorice allsorts, and as shiny as great smorgasbords of glistening salads and luscious seafood.

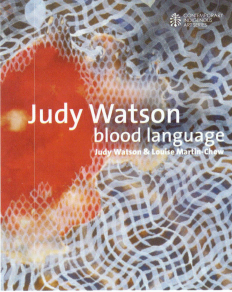

The handy and beautiful book 'Blood Language' on Judy Watson’s work is virtually a catalogue raisonné with many reproductions covering her career in great detail mostly accompanied by texts written by her explicating the work and positioning it in her oeuvre. For Watson, possession means looking at and responding to the culture of the past, whether that of her own people or human culture in general. The airiness of Watson’s images gain from the intimacy of small scale reproduction and to have them all in one place makes her art practice both graspable and retrievable, every artist’s dream.

The last two books I am looking at here are both published in Europe. For art history to move away from Eurocentric thinking, which may one day be effortless, is in fact quite difficult. Over the last few years ‘inter-cultural’ as a term has replaced ‘cross-cultural’, the term ‘world art’ has appeared, meaning, as Emily Kngwarreye may have put it, ‘whole lot’, countries and peoples work at writing their own art histories yet who speaks, who decides, who publishes, who buys and sells, who possesses the power, to tell the big stories, to be heard, still?

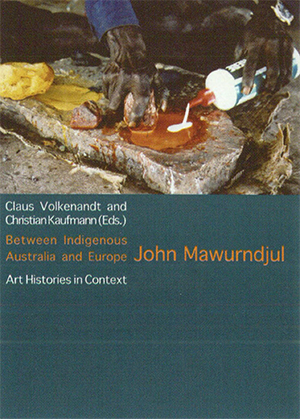

'Between Indigenous Australia and Europe: John Mawurndjul' is the papers of a symposium held in Basel at the Museum Tinguely in September 2005 when a large show of Mawurndjul’s work was shown alongside bark paintings belonging to the Basel Museum and collected by Karel Kupka in the 50s and 60s. The speakers ranged from Australians working in the field for years like Luke Taylor and Jon Altman to Europeans such as Jean-Hubert Martin, curator of 'Magiciens de la Terre' in 1989 and Bernhard Lüthi who curated 'Aratjara' in 1993. Yet it is a European-flavoured discourse and incredibly the convenors of the symposium, Claus Volkenandt and Christian Kaufmann, in their introduction write of the ‘old continent’ by which they mean Europe. I know that Americans and Europeans always call Australia a young country referring to its European settlement but surely they need to rethink that way of describing it. Isn’t that one of the truths that Aboriginal art draws our attention to? Australia is the oldest continent.

In his paper Paul Taçon wrestles with the separation of ethnographica into museums and art into galleries and suggests bringing science and art together into new Creative Centres. Anne-Marie Bonnet has her doubts about the usefulness of Aboriginal art being recognised as fine art: ‘Are Western art museums not mere terminals, mausoleums for formerly vibrant practices, and reservations for things that have become harmless? Maybe the Western art museum first needs redefinition as a place of vivid relevant practices - then it would possibly make sense to integrate Aboriginal art. We should cultivate differences and specificities instead of domesticating and ‘pasteurising’ them by turning them into fine art.’ Judith Ryan is one writer who brings an eye and a voice to describe Aboriginal art that actually relates it to non-Aboriginal art in a meaningful and significant way. She compares the materiality of bark paintings to Colin McCahon’s description of what he was trying to do on unstretched canvas: ‘I hope to throw people into an involvement with the raw land, and also with raw painting. No mounts, no frame and a bit curly at the edges.’ And she vividly describes their aesthetic. ‘The greatest bark painting contains a sensibility of design and surface texture, an inner life, a vital rhythm in the drawing... its power is not the result of technical facility or neatness, but the reverse.’

While once indigenous artists may have tried to avoid being seen as exotic they now tend to embrace their exoticism, their difference and capitalise on it as much as possible. Yet this often happens in a canny way where an artist takes advantage of the position engendered by their family background but opens it to broader concerns. Brook Andrew’s 'Theme Park' at the Aboriginal Art Museum of Utrecht known as AAMU (sounds a bit like 'emu' as spoken by a Dutch person) was an installation throughout the entire building rather than merely an exhibition. It pulled together works from collections of ethnography in Holland, Belgium and France as well as old and contemporary art, Andrew’s own work and stuff from his collection of Aboriginal kitsch and Australiana. The resplendent profusely illustrated hardback book that accompanied the show has essays by Marcia Langton, Nicholas Thomas and Anthony Gardner, an interview by Maria Hlavajova with Brook Andrew and three bookmarks in land rights colours.

.jpg)

In his introduction AAMU curator Georges Petitjean points out that the Aboriginal people of Australia have a special historical place in the European imagination not held by any other indigenous people such as those of Africa or America – he explains this to be the case on the basis of distance and the lack of political engagement or shared history with them, thus they can remain noble savages ‘blending harmoniously with the alien but desired landscape of Australia, and possessing secrets … lost to Europeans in the darkness of time.’ AAMU seeks to counter this romanticisation and ‘positions itself as a space for contemporary art, and a laboratory for exploring relations between Western and non-Western art, peripheral and established art’. Thus its focus on Aboriginal art could as well be on all Australian art. Yet according to AAMU’s website: ‘The goal is to get the general public excited about the unique character of this art form and the artists, who draw their inspiration from the oldest living culture on earth, namely that of the Aborigines in Australia.’

Andrew enters this charged arena with a cosmopolitan outlook and a clear sense of what it is to be an Australian artist as well as an Aboriginal artist which is refreshing. On the isolation of Australia from the rest of the art world he says in the interview with Maria Hlavajova: ‘Maybe Australia is seen as another ‘England’ or ‘America’ which is offensive to Australians. We are making art outside these boundaries and art that is both social and political, regional and global. . .The complexity of our cultural heritage in Australia is often unknown or misunderstood by the outside world...The problem is that Australian history is hardly registered by the American-European art world...It’s as if we don’t exist - but we clearly do.’

I think of Pakistani-born Rasheed Araeen who began the magazine 'Third Text' in 1987 in London in order ‘to examine the theoretical and historical ground by which the West legitimises its position as the ultimate arbiter of what is significant within the field of art and visual culture.’ When 'Third Text' began there was a notion of the ‘third way’ in which the world would be less clearly divided between centre and periphery. However it is a messy business. Third Text seems bogged down in dense academic contortions and the question remains, is it possible that change can occur or will dissenters, the ‘others’ always be simply co-opted or ignored? Araeen wished and still wishes his artwork to be accepted as part of the canon of art like all the artists he admired and emulated yet any Australian or New Zealander could have told him this is a tough call though it does happen very occasionally and very peripherally. Should we care? Can we write our own history? Start another centre?

These questions are also explored in the 'Theme Park' book by Anthony Gardner, whose chapter is called 'The Skin of Now: Contiguous Histories'. Gardner begins with quotes from Okwui Enzewor and Francesco Bonami denigrating Australia that show these two ‘leading exponents of a de-nationalised art’ demonstrating both their ignorance of and lack of interest in Australian art. Gardner, who undoubtedly admires these men and expected to find open minds in them, points out that stories of discrimination span the globe, that contemporary art about loss and dislocation comprises a worldwide web of contiguity that seeks ‘to counter geo-cultural hierarchies through more profound inter-cultural narratives.’

Rather than casting off Australian art and sitting back to reap the benefits of being connected to the world’s oldest continuous culture Andrew takes a much broader perspective on art and culture, on what it is to be alive now. This approach shares with Tracey Moffatt, who once famously rejected being called an Aboriginal artist though she frequently uses race narratives in her work, the ability to see the common boat in which we sit, and to tell the stories that cross cultures and imaginations to come to human terms with power, possession and the future. We are finally not other but same.