In viewing the body casts of the unsuccessful Pompeiian evacuees, one can sense the chaos and confusion in their curled or scrambling postures. Now, as they lie on the dusty hillside amidst birdsong and traffic noise, their reactions seem unsettlingly incongruous to their environment. In the same way, the ten, life-sized figures in Simon Gilby's The Syndicate seem to be responding to something we cannot see or hear and appear unaware of each other and of us.

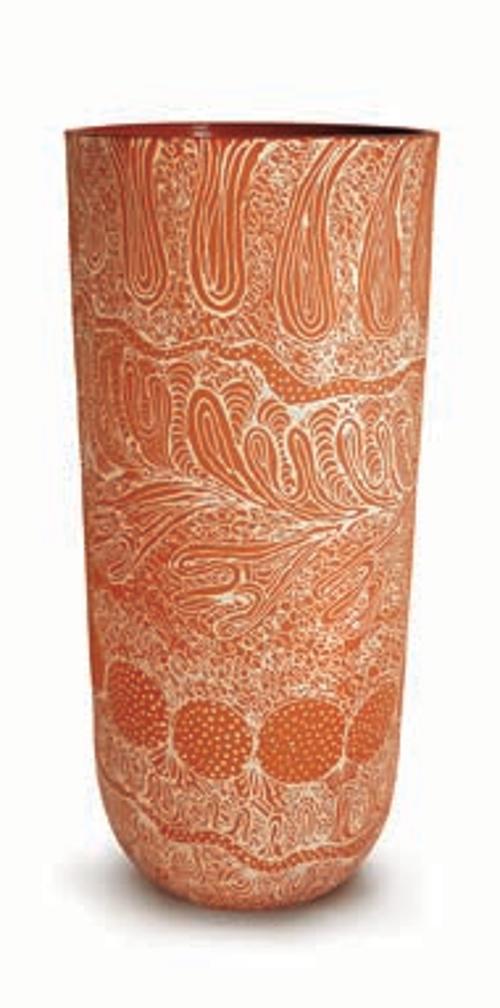

Fabricated from small, patchworked pieces of thin steel plate and ribbons of flat bar that have been scrolled and brazed into filigree, Gilby produced each hollow form from the moulds of ten life models he selected for their diversity. Whilst the bodies of The Syndicate members appear as husks that envelop the spaces once occupied by the models, the occasional insertion of detailed casts of their mouths, nipples, hands and feet can momentarily confuse this sense of absence. A broken fingernail or an unusually long second toe can so intimately describe the life once held within. Each figure is further enriched with surreal protrusions, etched images or text, or relic-like inclusions contained within the forms.

Messiah falls short of his traditional, heroic archetype; diminished by his position on the floor amongst us and his ordinary physique. Although his posture and emphatic hand gestures command our attention, we are distracted by the wheelchair that either pierces or grows from his torso. He seems unaware of this disturbing harbinger that is beautifully built in soldered stainless steel rod around his shoulders and chest. Fractured by the network of scar-like welds but still visible on the surface of Messiah is an etched reproduction of a 19th century drawing of a giant squid by the German naturalist, Ernst Haeckel who was later disgraced for manipulating his evidence to support his theories. Gilby uses this image, coupled with etched text from The Internationale, to describe our tendency to periodically embrace revolutionary ideals, however flawed their application.

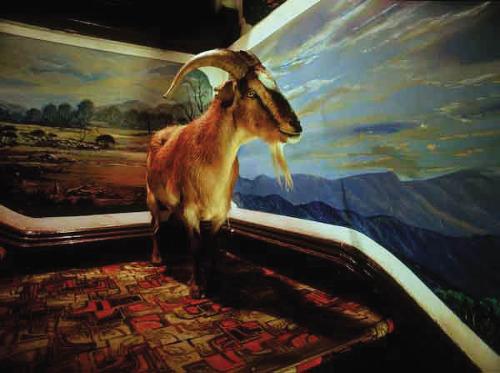

The Finalist is caught in a private moment of sudden realisation. The exhalation of surprise escaping from his steel lips is almost audible as he appears to notice the whale skeleton that pieces his torso. Sharing his shock, we wonder how and for how long he and the whale have so inextricably coexisted and how it has escaped his notice until this moment. On the other hand, Cadoux seems well aware of all she has witnessed and has done. Named after a wheatbelt town in Western Australia, Cadoux’s walking frames are marked with the lines of roadside water level indicators, and the vegetation that once sprouted from her sticks and grew through her form is brittle and lifeless. A raised, gritty foliate tattoo (made with sand from Gilby’s family farm) spreads across her polished form and bird’s wings on her shoulderblades, too small for her frame, lift her a little off the ground.

The Architect curls over in frustration, his head trapped in a geometric cage while Tarboy floats limply above his little plinth, looking up with an anxious question on his open lips. Confinement, petite, pregnant and almost upside down, appears preoccupied and self-contained as she orbits us with aerials and antennae built upon the soles of her feet.

The Syndicate is the result of a syndicated private commission that was initiated by Ron Wise (who had previously commissioned Gilby to produce a work for his winery) and managed by a passionate supporter of Western Australian contemporary art, Lloyd Horn. It enabled Gilby to expand his previous figurative interests to life-size scale and in number enough to present a collective portrait. Together, The Syndicate reflects humanity’s biological, technological and environmental contexts as well as some of the knowledge, beliefs, questions and anxieties we carry within.