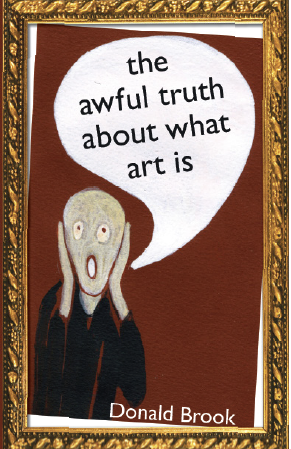

As an artist who is constantly being badgered to explain how what I do can possibly be called 'art', I am drawn to theories which attempt a definition of this most tricky of terms. Over the past decade, I have continually failed to satisfy my grandmother that a blog, or the ingestion of a bowl of cornflakes, or a goat tethered in a suburban backyard, might qualify just as well as paintings or sculptures as works of art. And yet, when I turn to the learned journals of aesthetics for help, I find myself faced with countless pages of bone-dry prose penned by zealous aesthetician nerds. Beside the mild intellectual thrill resulting from the illusion that I am participating in serious, grown up debates, reading such joyless pedantry texts tends to sap art's fun. To date, my research is yet to produce a useful working definition applicable in all circumstances, from which I can only conclude that one might not actually exist. Thus it was with a mix of trepidation and pleasure that I opened Donald Brook's new book 'The Awful Truth About What Art Is'. Surely, if anyone can solve this problem for me, Brook can. I have long been a fan, not only of Brook himself – a tenacious speculator on art, education and society – but also of the class of artist-academics of which Brook is a member: advocates of creative social practices in all their glorious plurality, old-school debunkers of artworld hogwash.

'The Awful Truth', as Brook states in his prefatory note, is not an idea without prior airing in the public sphere. Rather, this new book, published at the urging of Artlink editor Stephanie Britton, synthesises and coheres several of his previously published articles, rants and debates. The definition of art is at the core of 'The Awful Truth', but his is not simply a nitpicking footnote in the history of art's 'institutional theory', made famous by philosopher George Dickie. Brook, while acknowledging the circular logic of the dictum that art is whatsoever the artworld decides it is, lines up alongside my grandmother in viewing this legalistic definition as, at best, not particularly useful, and at worst, mealy-mouthed and cowardly. In common usage, the word 'art' means so much more than this. Brook strives for this evaluative and moving quality – something mysterious – something, importantly, related not only to 'necessary and sufficient conditions' but to actual interactions between humans and the world.

His contention is this: to date, there has prevailed a confusing conflation of the terms 'art' and 'work of art'. While happily conceding that particular 'works of art' obey the laws of the institutional theory, Brook argues that 'art', on the other hand, is something much more 'awful'. For Brook, art is at play whenever a revelatory experience opens us up to new ways of being in the world. This may inspire awe, it may create fear or pleasure or disgust. In any case, art is present at moments of revelation or epiphany, when the world is seen in a genuinely new light. What is alluring about this approach (remarkably akin to the pragmatist aesthetics of John Dewey and his followers, although Brook does not acknowledge the connection) is that art can be an integral part of all spheres of human endeavour: not just actions by artists in the artworld. This notion acknowledges something that is already instinctually felt in everyday life, embodied, for example, in the use of the word in describing such 'arts' as cooking, motorcycle maintenance, or jewellery theft. Art is a way of knowing the world through skillful material interactions. Furthermore, beyond such artisanal applications, Brook emphasises the creative and lateral leaps of faith that can occur unexpectedly in any field, when the surprising results of one's toil yield new insights. By carefully unpicking the terms 'art' and 'work of art', Brook moves us beyond the limitations of demarcational thinking embodied in an 'either/or' construction (either something is a work of art or it is not), and towards a more inclusive 'and/also' position. Art, he writes, is not the success or failure of a crafted attempt to achieve a desired outcome in the world, but the revelation or insight such success or failure may generate.

Brook labels this generation of insight 'memetic innovation' – a derivation of the term 'meme', coined in the 1970s by author and biologist Richard Dawkins. In Dawkins' formulation, a meme is to culture what a gene is to evolutionary biological systems. Memes are chunks of culture which spread within human society, expanding and proliferating, or contracting and becoming extinct depending on their ability to colonise our lives. Typical memes might include the tune to a popular song, this season's penchant for turquoise jeans, or a persuasive idea about how to revolutionise public transport.

Brook alters Dawkins' concept of memes, rejecting the notion that individual cultural items may evolve. Rather, for Brook, memetic evolution occurs only to broader 'cultural kinds'. Cultural kinds (he cites the birthday party, the daily newspaper, or the television set as examples) do evolve: particular instances of these kinds do not. Art, he claims, is neither a cultural kind (like 'landscape painting'), nor a particular item of a cultural kind (such as 'a landscape painting'), but rather an instance of revelatory memetic innovation, when new ways of being in the world occur to us.

Memetic innovation cannot be planned or legislated, but rather involves a creative responsiveness to surprising circumstances. It can take place in any field of cultural endeavour (not least in the sciences). For Brook, memetic innovation is a transcultural, timeless category of human experience. For this reason, art (like creativity, like invention) cannot be encapsulated within an evolutionary story. Thus one of art's 'awful truths' is that it can have no 'history' as such. One can of course speak of the histories of portraiture, bronze sculpture, or furniture design, as these are cultural kinds whose memes are subject to evolutionary processes. But art, understood as memetic innovation, is by definition an ahistorical phenomenon.

Although I found these ideas stimulating and challenging, they were not always easy to follow. Indeed, I am by no means clear that I understand Brook's argument in the manner he intends. Writing the paragraph above, I found it very difficult to compress and reproduce his concepts in my own words, and for this reason I fear that Brook's definition of art as memetic innovation will struggle to become a successful meme itself. Furthermore, the vast body of controversial literature stimulated by Dawkins' original text (about which, I must admit, I have only a very light grasp) means that the very concept of the meme suffers from the fundamental instability of its metaphorical base. Brook's association with this slippery concept may, unfortunately, serve to obfuscate rather than clarify his argument.

However, for those who persevere and it is not exhausting – 'The Awful Truth About What Art Is' fills a mere 140 pages – Brook's extended essay is an intellectually rewarding and provocative text. His erudite writing is light and readable, his voice at turns cranky and amused. Refreshingly, rather than fiddling at the edges of cultural analysis, Brook is never afraid to launch head first into the big issues. This is bound to generate disagreement and criticism. Judging from his recent embrace of internet publishing, wrestling with opposing viewpoints is something Brook considers to be an integral part of philosophical practice. His contentious online articles, applying rigorous and feisty analysis to contemporary topics ranging from the Bill Henson affair, republicanism, and the banalities of ageing and memory, often spark several hundred responses from readers. As Brook writes in 'The Awful Truth About What Art Is', 'the road to Damascus is not confined to a corridor traversing the great galleries of art. It passes also through the supermarket and the factory floor of common experience'. The contribution of Brook's new book lies, I believe, in his life-affirming belief in the power of engagement in, and reflection on the whole world around us – not just those things that the artworld promotes as 'works of art'.

The Awful Truth About What Art Is can be ordered online at www.artlink.com.au