'Open Air: Portraits in the landscape' is an important exhibition, complementing the popular outreach exhibitions run through the National Portrait Gallery and ABC websites. It is complex, demanding and provocative. 'Open Air' embodies the questions the new gallery must address now it has its own high profile space, questions it had been teasing out in previous shows at its temporary venue Old Parliament House. This is a keynote exhibition for the new public face of the NPG, leading the question of portraiture itself into the open air.

The installation establishes a series of conversations between portraits and self-portraits, well-articulated within the new architecture. There is space for contemplation at each point and room to stand back and appreciate the visual relationships. If there is to be a criticism of the exhibition it would be that the questions raised in Open Air are too large to be embraced in one show. Between the implications of Matisse's famous 1947 interrogation of the nature of portraiture:

'What is a portrait? Isn't it a translation of the human sensibility of the person represented? The only saying of Rembrandt's that we know is this: 'I have never painted anything but portraits'.'

which opens the catalogue essay and Tony Tuckson's 'Wind' (1970) (an abstract portrait of Renée Free) which opens the exhibition, the conversation is blown open to embrace almost all contemporary production. (Self) portraiture as the expression of identity and sensibility, divorced from any formal relationship with the outward form of the subject is a wide brief. However if the exhibition is taken as a keynote show designed to open up space for future conversations, it fills this role admirably.

Some portraits in the landscape deploy the expression of identity in relation to place in a relatively unproblematic way. Although we may not have previously seen them as such, Sidney Nolan's 'Daisy Bates at Ooldea' (1950) or 'Burke and Wills expedition' (1948) are portraits of individuals whose public identity is inseparable from place. They may differ in tone but in visual vocabulary these works are recognisable descendants of Sir Joshua Reynolds' portrait of Sir Joseph Banks posed with maps and open window. But what possibilities does a more open conception of portraiture raise in a country for whose people place has always been the distinguishing cipher of identity? For me this was the really exciting part of the exhibition. Here the curators have set up a conversation between the artists, the sitters and the landscape to explore an open-ended conception of identity and portraiture.

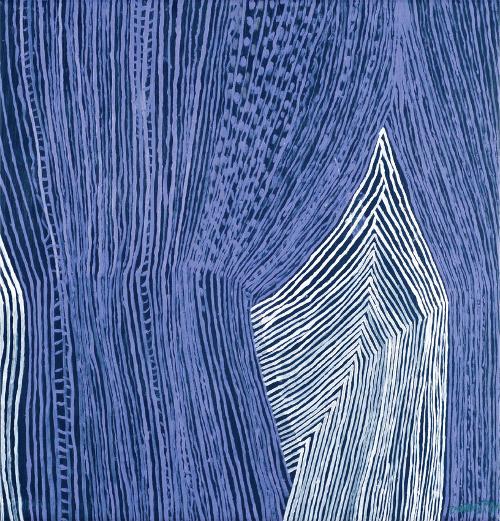

Once a definition of portraiture as the visible expression of identity is accepted we are drawn to embrace the huge Indigenous tradition of representing identity. The exhibition opens with pukumani poles by Tiwi artists Mickey Geranium Warlapinni, Enraeld Munkara Djulabinyanna and Bob One Apuatimi. The catalogue quotes Paddy Freddy Puruntatameri as saying that 'pukumani designs are to make posts like people'. Abstract markings portray an individual's identity as a network of relationships with the land and cultural markers.

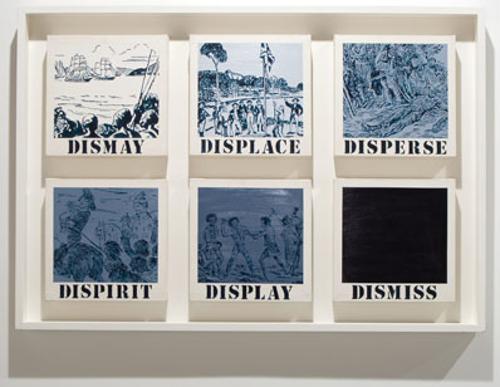

This part of 'Open Air' establishes a conversation between portraits and self-portraits around differing relationships with the land. 'Christmas Eve in the land of the dispossessed' (1969) by Kevin Gilbert is a naked expression of longing for an idyllic past in the context of a dispossessed present. This work is paired with Ellie Gilbert's photographic portrait of 'Kevin Gilbert, near Taree' (1988) where the artist appears almost indistinguishable from the land. The visual languages deployed are poignant expressions of a desire to reclaim an untroubled relationship with Country.

Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri's painting 'Trial by Fire' (1975) is positioned as a self-portrait; the artist's identity is articulated as inextricably linked to his relationship with the land and a cultural past. This is a very different sort of portraiture to the Western tradition which identified the individual by their difference. Andrew Sayers makes the point in the foreword to the exhibition catalogue:

'National portrait galleries have been traditionally predicated on the idea that identity can be equated with individuality. In Australia, however, we have Indigenous traditions in which identity is actually lodged somewhere else – in relationships and in people's relationships to land.'

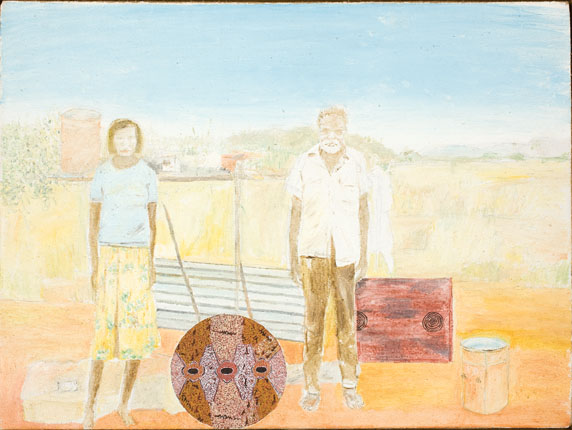

Against Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri's commanding expression of identity is positioned the portrait of 'Daisy and Tim Leura' (1982) by Tim Johnson. In this work we see Johnson setting up the Western tradition of portraiture as it grapples with a visual language and cultural tradition which are fundamentally alien to it. Johnson's juxtaposition of Indigenous and Western traditions around identity, power and portraiture makes a telling work. This intersection of cultural traditions exposes both the vulnerability of our visual language systems and the frailty of those operating outside their own system. There can be no easy reconciliation between cultures whose conceptions of identity are so fundamentally dissimilar. The hope is that exhibitions like this one, which articulate points of conversation, are another step in a long road.

Understanding who we are and how we want to be remembered is a large and ongoing project.