The Queensland Art Gallery's latest major exhibition sets itself an intriguing project, to survey the threads of optimism in contemporary Australian art. What does it mean to be optimistic today, and in what aspects of life do we build our hopes? The theme of optimism is a broad brush but QAG's curator of Australian Art, Julie Ewington, places focus on 'an upbeat and joyful edge' and 'the positive, celebratory, and redemptory, creative potential of art'. Many of 'Optimism's' artworks are indeed bright, bold and breezy but the collective impact of this survey is neither joyful nor particularly upbeat. A cumulative impression of restrained and somewhat contrived optimism develops, creating a vision of a future deeply aware of social and political realities.

Unexpectedly, the exhibition is almost devoid of romanticism and utopian dreams, as though the complexities of what is wrong with this world negate belief in a better life. Numerous film pieces by artists such as Ivan Sen, Clara Law and Rolf de Heer explore inevitable human fallibility and the pendulum of privilege and deprivation. The film genre's precision in reconstituting reality is confronting, unrelenting, and whilst sometimes humorous, far from 'upbeat'. Yet there is no sense of pessimism in place of optimism. Film creates the fine edge of a gritty pragmatism, born from the hindsight of unrealisable twentieth century ideals and values. Whilst sceptical about 'a better world', there remains an imperative for 'a different world', and this is, perhaps, the contemporary face of optimism after all.

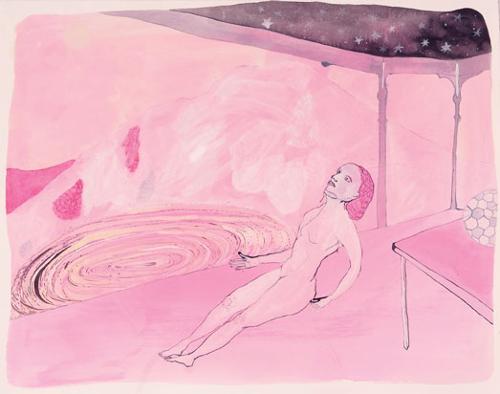

Confronting political and social realities across the full scope of mundane everyday and 'historic' events are what distinguishes contemporary art from the past, and why much of the art in this exhibition reflects 'pragmatic' optimism. Joyfulness is not obsolete today, but it is hard-won and contingent on the perspectives of 'others'. Stephen Bush's bright surreal landscapes are acidic rather than joyful, and steeped in impenetrability and uncertainty. They are perfect locations for the vulnerable, exposed figures in Del Kathryn Barton's series titled 'I am flesh again' (2008). Her pen and watercolour drawings make a haunting statement about optimism, as disengaged eyes register the soul of hope trapped in the flesh of self-identity. These figures are transgendered, whimsical and lost, but they appeal to the human survival mechanism in a potent manner.

Cartoon, graffiti and pop art imagery also feature in the exhibition and underscore a subversive and relatively cynical take on optimism. Just as photography bears its 'apparent truth status', cartoons and graffiti are icons of social and political critique. Inclusion of Michael Leunig's huge wall painting reminds us of the gut-punching strength of cartoons and their capacity to harness and mould opinion. Julie Ewington describes how the exhibition developed increasingly towards: 'How artists invent the world. We wanted to show artists acting on the world and their refusal to lie down. The theme of their agency became stronger.'

The 'fisho-sign' style of Robert Macpherson's installation comes at 'opinion' from a different angle to Leunig, and reflects the ad hoc and apparently random nature of life, where meaning fits into the spaces it is given. With Leunig we carve ourselves a future with scalpel blades, but with Macpherson optimism moulds itself around circumstance and surprise. These two works are large wall installations that innately pair as modes of popular or vernacular aesthetic, and whose presence shapes our world far more than we acknowledge.

The thematic complexity of these 'gritty' artworks tends to limit the credibility of hard-edge abstraction as a contemporary expression of optimism. There was a time when the bold, bright colours and purity of expression of modern art were implicitly optimistic, but as statements about life they now seem like tunnel-vision, too driven and too 'hard-edge'. In the twenty-first century we do not relate easily to the apparent essentialism of pure form and colour. Robert Owen's 'Aura (Ten eye colours)' (2003-8) is colourfully upbeat and pleasurable, but not fresh and rings hollow against other expressions of contemporary optimism. This modernist aesthetic still has a place in our world, but it now fails as a vehicle for visions of the future. Mark Galea's sculptures of interlocked coloured acrylic sheets bear titles of 'newness' such as 'A new light on the meaning of new dance steps' (2008), and 'Components for the construction of a positive outlook' (2008), and whilst they have an ironic 'Ikea' contemporary familiarity, their 'positive outlook' remains embedded in the twentieth century.

'Positive outlook' takes a reality check when considering the Indigenous artworks included. Against the social and political realities of Australian Indigenous existence, 'optimism' is potentially tokenistic, to say the least. But far from being tokenistic, the Indigenous artworks soar like eagles of pragmatic optimism in this exhibition. The future is always already with us in an Indigenous worldview. A person is their past and their future at once, so the circularity of life is a form of optimism in itself. This is a survival mechanism and why Indigenous people are so adamant about 'keeping the Dreaming alive'.

Folding the chapters of past, present and future into one outlook is why George Nona's Torres Strait Island 'Ceremonial Dhoeri' (head-dress) (2008) artworks do not suffer from the anachronism of the modernist aesthetic. The presence of these dhoeri as artworks in a gallery rather than ceremonial artefacts in a museum, attests to the cultural re-invention of Indigenous people. Through the pragmatic optimism they create these dhoeri to engage in the contemporary world of art institutions and markets, they reinvent their 'outlook' so that their 'in-look' survives.

Will Stubbs' catalogue essay is a brief but brilliant explanation of how Indigenous Dreaming embodies optimism by regarding how Nawurapu Wunungmurra's selection of ceremonial poles appeals to a different way of thinking about time and how this impacts on an entire outlook of life. Stubbs writes:

'In Yolgnu grammar, the wind blew/blows/will blow concurrently in a temporal dimension that encompasses prehistory/the present/the unknown future. We don't have this declension in English. All the events of sacred narrative take place in this 'everywhen', which Western thought does not readily embrace. .. In these five memorial poles, the wind disturbs the water, imbued with the apocalyptic tragedy of this ancient and future tsunami, into zigzag chop.'

The power of 'everywhen' is redolent in the art of Nona, Wunungmurra, the Western Desert Kayili artists, and even Sally Gabori's Mornington Island freewheeling paint explosions. And Indigenous art from urban backgrounds sustains the 'everywhen' in a more overtly political and socially-conscious environment. Vernon Ah Kee's word-pictures frame the entry to the exhibition, and act as a kind of gate-keeper. Hovering throughout the word-pictures are Ah Kee's Ned Kelly inspired Red Hat figure, whose origin is an anagram of hatred. Yes, this is a dark side of optimism, but the gate-keeper to this exhibition is the metaphoric gatekeeper of our access to optimism in today's world.