Corrosion is at the core of things, a process that once begun seems to accelerate towards dissolution, the reduction of things to their fundamental forms. The elemental is here everywhere in evidence, black carbon, rusty ochres, bloody ink, in crusty surfaces, the layering and tearing of paper and the salt crystals heaped in tidal lines along the cool concrete floor of the gallery.

A large ochre form is encrusted on the floor, an unhealed wound at its centre is heaped with bright salt crystals, a fragile ti-tree fence (shelter, hide?) hangs nearby in a sinuous curve, on the wall next to it wax ears (cast from life) are pinned with galvanised nails to the wall, the connections between these elements are tenuous but potent, unmistakable. Judy Watson's salt in the wound could be our corrosive core; blood, rust and brutality rendered in powdery ochre and soft wax.

For the artists in Shards, Judy Watson, Yhonnie Scarce and Nici Cumpston, fragmentation becomes not breakage but a loosening of bonds and an examination of the spaces revealed, a productive process of reconstruction. These elements of colour and texture, of the organic processes of growth and entropy, resonate and reflect, building a web of multiplying interconnections and opening up spaces and pathways for the accretion of meanings.

Watson's artist's book, a preponderance of aboriginal blood, shown as sixteen etchings, uses archival material on the Aboriginal protection system exploring these systems of bureaucratic control over Indigenous people and the complex classifications of proportions of Aboriginal and White blood that lay at its core. The etchings are quiet, stained with bloody ink, the work shocking in the absolute matter-of-factness of systemic oppression; the use of 'breed' on forms to refer to Indigenous people, the casual arrogance of an official who simply cannot understand why an Indigenous woman exempted from the Protection Act might think this entitles her to vote. Reading the work is an oppressive experience, the ink almost obscures the text in some cases forcing the viewer into an uneasily close intimacy, it feels like entrapment, smothering in layers of paper. Watson's use of the chine collé process is refined; and her potent layering and binding of the language of control to the paper and overlaying it with red ink that seeps and stains exposes the fear of the irruptive other that drives the need for classification and control.

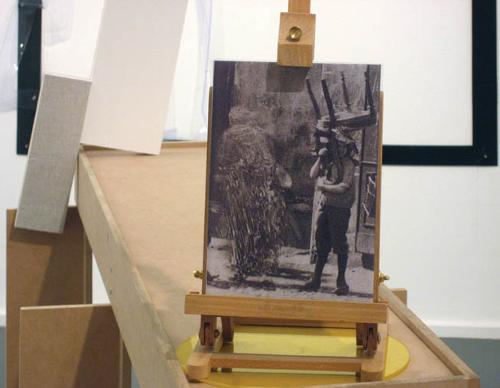

This layering is echoed in Yhonnie Scarce's family portrait in the roughly peeled-off labels on the grog bottles that leave behind white strips and shreds. Starkly, purposefully black and white, contrasting with the reds and ochres of Watson's work and the greys and pastels of Cumpston's river images, family portrait is a series of floating white shelves stepping down the wall in a familiar genealogical pattern. Most contain an empty bottle (bourbon, whisky, beer, metho), some a rough black cross texta-ed on the label, others a rudimentary stick figure bound in black thread inside denoting a death or family member dying from alcohol. Family portrait couldn't be framed in starker terms but Scarce inverts the expected, the empty shelves are those of family not affected by alcohol, resistance is marked by absence and blankness becomes populated, hopeful.

Where blood and alcohol flow as a connecting thread through Watson and Scarce's work, water or its absence is at the core of Cumpston's large scale images of Nookamka (Lake Bonney) where drought and water mismanagement have starved the lake possibly beyond saving. Yet the pastel tones of Cumpston's images of dead and dying trees on the exposed lake bed robs them of the urgency that might crystallise them into powerful images.

Watson's women's neckbands and asmodea is revelatory, an Indigenous woman's neckband floats like an umbilicus over the monolithic form of Goya's mountain, Asmodea. With this connection between a woman's adornment and Goya's history, it is impossible not to think of the Spanish artist's depictions of the individual and particular horrors of war or to resist the almost visceral realisation that there was a war and it was here.