Last year Emily Floyd happened upon a radio program on Australian political posters of the 70s and 80s. That program interviewed artists involved in the Earthworks Poster Collective housed at the Tin Sheds on the grounds of Sydney University. In the early 1970s students and activists gravitated to the screenprinting facilities on campus and used them to promote everything from film screenings to land rights rallies, protests against nuclear power plants and marches for feminism. Oscillating between anarchy and mysticism – a call for world harmony on the one hand and revolution on the other – Earthworks posters vividly encapsulated the contradictory rhetoric of the times.

Something of the explicit social engagement and the collective spirit of Earthworks posters are present in Floyd's latest exhibition It's Time. Floyd was awarded the Australian Print Workshop 2007-2008 Collie Print Trust Fellowship (other recipients have included eX de Medici, Louise Weaver, Thornton Walker and Aleks Danko, a Tin Sheds fixture). The fellowship was established to allow artists working in various media to undertake their first significant printmaking project. With the assistance of APW's experienced printers Martin King and Simon White, Floyd has produced nine limited edition prints that draw inspiration from the political posters of the past.

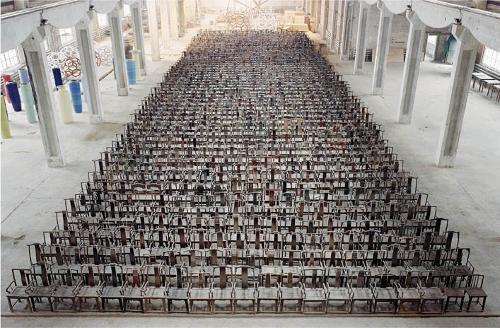

Floyd is primarily known as a sculptor. Over the past decade she has mainly worked with critical and canonical books. Her process involves selecting passages of text, nominating a particular typeface then rescaling the letters before rendering them in three dimensions. These typographic objects – made from materials ranging from mdf to wood depending on the project – are arranged by Floyd in the gallery space either on their own or with accoutrements. Although each of her exhibitions has been distinctively different, their whimsical configurations often recall the miniature cities that a child might assemble out of blocks. Re-imagining these texts as spatial environments the installations perform, as it were, the encounter between a reader and its audience. The kind of mapping that Floyd undertakes is a transcription, of sorts, but one authored by an idiosyncratic translator. Furthermore, the installations enact in some way the process a book undergoes from a mute object into a communal experience and, in the instance of The Female Eunuch, a cultural force.

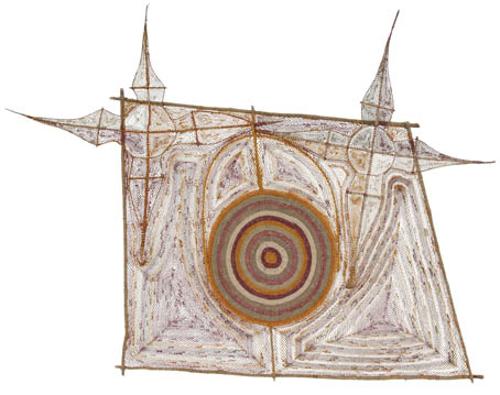

In the exhibition Temple of The Female Eunuch (Anna Schwartz Gallery 2008) Floyd turned her attention to Germaine Greer's seminal feminist tract. The book's now infamous cover art by John Holmes, a suit in the form of a woman's body, is reworked by Floyd into an organic shape carved from wood. Many of the formal aspects of the exhibition – Floyd's selection of warm colours, earthy materials, a circular motif and the uniquely hand-rendered display type – are further developed in the printed posters on display at APW. In addition to The Female Eunuch, Floyd has drawn on several other key texts from the 1970s. These include David Gulpilil's performance in Storm Boy, Gough Whitlam's historic speech from 1972, Bill Mollison and David Holmgren's environmental treatise Permaculture One, and the lesbian love novel All that False Instruction. When you think about it Floyd's excursion into printmaking is a fascinating doubling back, returning as it does to the origins of her sculptural practice, the printed word.

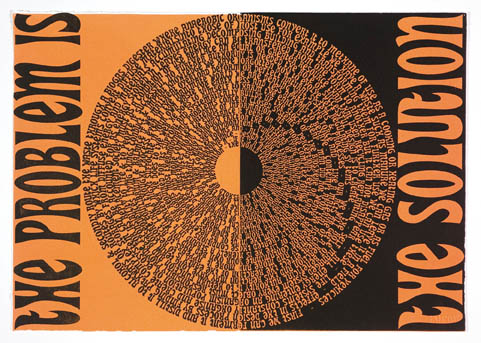

Utilizing aquatint, an intaglio printmaking technique where texture is applied onto a plate (in this instance both copper and aluminium) Floyd's predominantly small works make bold proclamations such as 'It's Time' and 'The Problem Is the Solution'. Arranging the type into simple shapes, particularly circles, squares and diamonds, the prints bring to mind the principles behind alternative education philosophies (Floyd is clearly fascinated by the subject, she has exhibited an oversized Steiner rainbow in the past). The semi-circle arches of the prints recall that earlier work. And something in the way that the prints are designed to fit together to create a continuous circle intensifies the statements and excerpts found within those simple shapes. That's an eye staring out at you. Densely printed in ever-narrowing bands, the text produces a strangely vertiginous effect. Staring at Floyd's prints you feel poised on the cusp of a mystical revelation. Something is definitely going on. It's time all right, but time for what?