Despite the withdrawal of paintings by Desart art centres in central Australia, the 25th National and Torres Strait Islander Art Award exhibition was of a high standard featuring diverse, stimulating and innovative artworks.

The 2008 judges were Art Gallery of New South Wales Indigenous art curator Hetti Perkins and the 2006 winner of the NATSIAA Work on Paper Award Queensland artist Judy Watson. Pintupi Elder, Mukinti Napanangka won the Major Award for her painting Untitled. She overlaid a deep red ground with yellow, mauve, orange and flesh coloured brushstrokes of dynamic energy in this work related to the tracking woman dreaming story connected to the Lupulnga rock-hole near Kintore.

Doreen Reid Nakamarra won the General Painting Award with an impressive, large scale painting Untitled associated with the rock hole site of Marrapinti in Western Australia. Terry Ngamandara Wilson from Gochan Jiny-jirra in Arnhem land, took out the Bark Painting Award for his intricately painted rarrk (crosshatch) work Gulach – Spike Rush a vegetation characteristic of his clan country that surrounds the Barlparnarra swamp.

Whilst these were all aesthetically outstanding paintings the highlights of the exhibition were works that pushed the boundaries of their chosen art form, notably the winner of the Three Dimensional Award: Gatapangwuuy Dhawu (Buffalo Story) Incident at Mutpi (1975) by Nyapanyapa Yunipingu. It consists of a bark painting by Yunipingu beneath which is shown a DVD of the artist telling a group of local children about the dramatic incident when she was gored by a buffalo. Whilst telling the story, Yunipingu refers to her bark painting, pointing to the two fish, the tree her two companions climbed up to escape the buffalo, the dog and the buffalo itself with its long horns. The story is a personal one and is not concerned specifically with Yolngu belief, making it easily accessible to a non-specialist audience from a non-Yolngu cultural background. Incident at Mutpi reveals how bark paintings operate within the four dimensional environment of communities as language, gesture, spiritual beliefs and the painting all play a part in conveying meaning. In making the multi-dimensional significance of the bark evident, the work begins to bridge the wide gap between the work's role as a 'fine art object' within the 'white cube' gallery space and the part it plays within the social context of a remote Arnhem Land community. Importantly, the production of this work was possible because of the Mulka multi-media training project based at Yirrkala in North-East Arnhem land. This enables Yolngu to gain the necessary film production skills to tell and produce their own film stories.

Innovation was also a feature of Dennis Nona's work entitled Dugam which took out the Work on Paper Award. Nona won last year's award with his gigantic bronze crocodile Ubirikubiri. This year, Nona again stunned viewers with his technical daring and prowess by producing a large-scale etching in which the detailed, etched plate itself is cut into the shape of an intricate yam vine. This work along with Koewbuw Dhoeri a glorious white feather headdress by George Nona and Adhikuyam a detailed, large-scale linocut by Alek Tipoti, bears testament to the quality of Torres Strait Islander art.

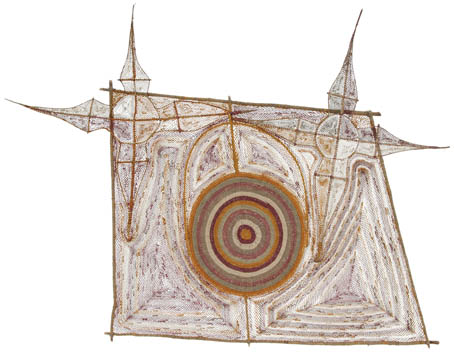

The quality, diversity and innovation of the fibre art submitted to NATSIAA continues to develop following the success of the Tjanpi Weavers who won the Major Award in 2005 for their Tjanpi Grass Toyota. This year Syaw a fishnet made from knotted sand palm fibre and bamboo by Kathleen Korda and Djerrh kunngobarn mileruhrurrk a knotted stitch bag made from pandanus by Barbara Gurwalwal were both exquisite examples of the fibre art form. But the stand-out piece was Dirdbim (full moon) by Marina Murdilnga of Arnhem Land. It hangs on the wall like a painting making a dramatic bid for equal status with canvas artworks. Dirdbim utilises innovative pandanus weaving techniques to depict a tightly woven, multicolored circular moon framed by two stars created out of network. The stars literally burst out beyond the wrapped stick pandanus frame.

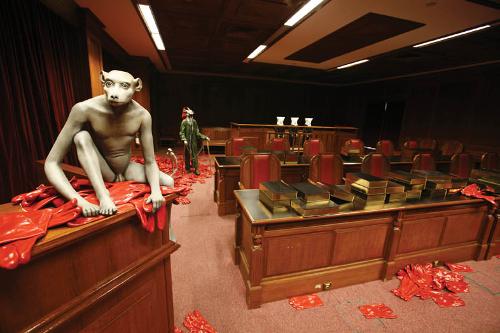

I was surprised that Danie Mellor's Exotic Lies and Sacred Ties failed to receive a merit award and was not purchased by MAGNT. The work consists of a large gilt frame in which is presented a landscape, reminiscent of the 'exotic' scenes characteristic of English Spode blue and white china. The stuffed parrot and upside-down cockatoo that hang above the landscape recall the bizarre renditions of these birds produced by European artists following the eighteenth century European voyages of discovery to Australia. In front of the 'landscape' are two mosaic kangaroo 'messengers.' One kangaroo points to the painting. Another covers his ears in a 'hear no evil' gesture, graphically signifying how under the black armband view of history regime, the oral history accounts of Indigenous people have been largely ignored. This work recalls the museum dioramas in which Aboriginal people, who until 1967 were classified under the Flora and Fauna act, appeared amongst exotic taxidermy objects.

Mellor's work highlights the need for more critical debate surrounding the actual works in the Award. To this end, debate and criticism should not be dismissed as negative publicity that endangers sponsorship. Rather, NATSIAA should be seen as a catalyst for critical discussion.

This year, discussion was dominated by the decision of seven Desart centres to pull out the work of their artists in protest against a dealer whose artists were included in the Award. The dealer is alleged to be guilty of unscrupulous dealings. But did this reactive strategy of withdrawal from the Award fully benefit Indigenous artists or did it effectively shift the focus from the artists themselves to the dealers, galleries and art centres representing them?

Certainly, the lucrative nature of the Aboriginal art market has created a new situation in which the lines between the artists, art centre and galleries are no longer clear-cut. In this new environment, art centres must be adequately resourced to respond to this situation effectively. The recommendations of a Senate inquiry into the Indigenous art industry will emerge soon. Presumably it will cover some of the wide-ranging questions that need to be asked. Why are Indigenous artists susceptible to carpet baggers? What training is available to art centre coordinators in terms of ethical practice, governance, marketing and training? Why is the vital role art centres play in maintaining and promoting cultural practice within communities not fully acknowledged by media reports such as the Four Corners special: Art for arts sake?

With the introduction of Aboriginal art awards in other states and territories, the structure and role of NATSIAA will also come under review. Should the Award be a Biennial one? Should the judge and pre-selection committee be combined – and be appointed for more than one year so that broader artistic trends can be identified and followed? Should the Award categories be recast to reflect 'innovation' and 'lifetime achievement' as writer Nicholas Rothwell has suggested?

Whatever the changes may be to NATSIAA, its distinctive character as a top-end based Award that encourages innovation and that supports 'emerging artists' should not be lost. This year's 25th anniversary NATSIAA exhibition certainly reflected these qualities.