Funeral flowers have always disturbed me. While they are usually offered with notes of regret and sympathy, their bountiful plumes and floral sprays echo the cold reality of death. More than likely, a few hours after delivery they will join the deceased in their descent six feet under or be plunged into the blazing furnace of cremation. I can't help lingering on their inevitable decay, slowly fading out of this world; a mournful reminder of the loss of life and the firm finality of death.

For 17th century vanitas painters, the withering flower was a fitting symbol for time, loss and transience. Purposefully designed to remind us of our mortality, earlier versions of vanitas paintings featured skulls, books, jewellery and musical instruments, objects considered to be vain symbols of earthly accomplishments and pleasures. Using contemporary funeral flower arrangements in a similar way are the photographic works of Ornament, an exhibition by Hobart-based artist Anne MacDonald.

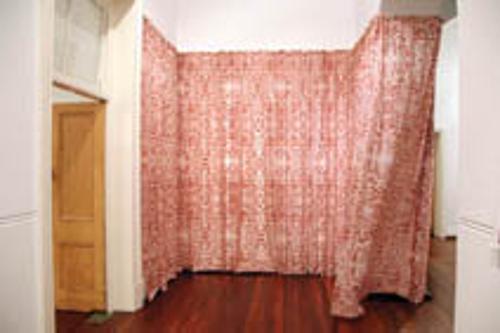

Presented as a large-scale installation of round black and white ink-jet prints, Ornament fills the gallery with a strange sense of uneasy splendour. The air is heavy and the lights are dim. Spread over the walls in neat succession, the clusters of photographs reminded me of how collectible plates might be arranged in a lounge-room. Nesting in the centre of each image is a carefully arranged wreath of flowers. Initially, I assumed the flowers are real yet on closer inspection I started to see small flecks of decay. Not a withering decay, more like the disintegration of weathered stone or mouldy cheese. The perky buds and matte leaves celebrate the cloudy shine of plastic and the curl of every petal has the lop-eared look of fabric.

In each work MacDonald has manipulated a subtle use of muted colour to great effect, making it difficult to decipher what could be real and what is artifice. The dark spaces seem velvety, almost soft to the touch while pale greys shimmer effortlessly into white. This gives the images a surface 'warmth' that momentarily masks their disconcerting purpose. The configurations of flowers, leaves and ferns are sumptuous. Some include ceramic doves, clasping hands, cherubs and the consoling phrases, 'At Rest' and 'In Loving Memory'.

Presented by the living as tokens of remembrance, graveside ornaments reassure those left behind that the deceased is in a safe place, peacefully sleeping rather than lost forever. They serve as comforting beacons in the face of darkness, even if their petals are ragged and sun-bleached. Taken out of their context, these ornaments become objects of detached beauty. Their circular design echoes the cyclical nature of birth and death while the lush artificial blooms suggest a state of eternal life; a life not ended but momentarily 'stilled'.

While MacDonald's flowers might offer solace in their beauty, they also maintain the fiction of death. They mask the reality of our demise. They hint at an attractive decay yet hide the rot and the fluids. Gone are the days of post-mortem daguerreotypes, where the dead body was something to photograph and view repeatedly as a keepsake. Now death is a relatively private affair, reserved for family and with most of the gruesome details evaded. Flowers, angels and doves have become the modern, more palatable face of death.

Originally built at the turn of the 20th century as the Tasmanian Public Library, the lofty classical design of the Carnegie Gallery is a fitting space for MacDonald's work. The high, arched ceilings echo celestial aspirations of cathedrals while the sparse, polished interior lends a hauntingly clinical feel to the otherwise grandiose setting. Marking MacDonald's latest investigation into a subject she has been exploring since the 1980s, Ornament is a delicate yet complex interpretation of the aesthetic and philosophical significance of funeral flowers and graveside mementoes.