All Biennales are about memory. What do you remember about the first Biennale you saw, or the last one? What do you remember about the art of the past, about the art history you were taught or read or collected from experiences in darkened rooms, on the edge of rivers, or from pressing your nose up to objects in glass cases? What, on arriving home and sitting down to write, can you remember about any Biennale except quickly moving from work to work trying to see everything but always knowing you will miss something, just out of reach of your time or strength, which will appear later in someone else's story of the best thing they ever saw? And what do you expect from a Biennale anyway? And who are they for? Like combination pho, noodles or fried rice the 2008 Biennale of Sydney seeks to be for everyone, the teachers, the students, the general public and the connoisseur&something for everyone without having to choose between chicken or prawns, pork or tofu.

Starting at the AGNSW a deep sinking déjà vu came over me as I saw Bruce Nauman's The True Artist and Marcel Duchamp's Bicycle wheel looking very clean and shiny, both borrowed from the National Gallery of Australia. By the time I saw Pierre Manzoni's can of artist's shit I felt like I was back at art school though I think maybe even first year students would be wanting to turn the page. Yes there were fresh things to see like Raquel Ormella's Wild Rivers: Cairns, Brisbane, Sydney drawings and James Angus' astonishing Bugatti Type 35 and Lia Perjovschi's alternate histories and Jannis Kounellis' Untitled (Carboniera) a container of shining crystalline coal (and maybe it is not so much that I object to seeing old things as so many of the same old things) BUT...

Eighteen years (a generation?) after René Block's 1990 Biennale of Sydney which was subtitled The Readymade Boomerang : Certain Relations in 20th Century Art the 2008 Biennale curator Caroline Christov-Bakargiev has chosen to run the viewer through the well-trodden lineage of the accepted 'revolutionaries' of European and American avant-garde art, again. Now the story does include New Zealander Len Lye and some Eastern Europeans and South Americans (though no Australians of the era except for a tryptych by Richard Larter and a retrospective of Mike Parr out at Cockatoo Island) but all the same it does seems a little dull to be surveying this particular art story again. Of course the retrospective turn is globally very fashionable, the last Kassel Documenta was chock-full of it, and it is all too evident in many reenactments of iconic performances and reconsiderations of movements that began in the Sixties. It is presented as a return to the possibility of utopian thinking (the 'very important' artist Joseph Beuys said every human being is an artist) but do we need a return? Is it not the case that every human being is now an artist on U-Tube? When will Europeans understand the major truth of postcolonialism that the history of the world is not the history of Europe and America? Is it is a last gasp of cultural imperialism that brings the truth of art to us, who live here 'down under', as some kind of revelation. Christov-Bakargiev writes: 'I thought the Biennale of Sydney was an interesting context to think about the concept of an upsidedown world.' Revolution or revelation?

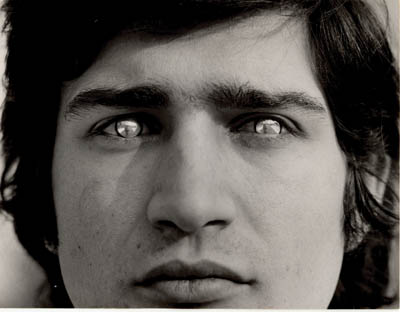

At the Museum of Contemporary Art somehow the mix of old and new worked better than at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and Alexander Calder's mobiles had an impressive amount of space in which to turn and swing, their shapes delicately shifting as people walked around them. Guiseppe Penone's To Reverse One's Eyes where the eyes of the artist are covered with mirror contact lenses is good to look at because of its 'revolutionary' briefness as a video and because the place where Penone walks looks like a scene straight out of a movie by Pasolini.

Christov-Bakargiev is the first Italian to curate the Sydney Biennale, an event that was begun by an Italian immigrant, and her approach is poetic though dry. The catalogue, a black and white book of quotes, drawings and excerpts, devotes a page to John Cage's words: 'There is poetry as soon as we realise that we possess nothing.' There was a definite feeling that this is a BB (Budget Biennale) and lack of funds was mentioned at press events. (By the way who is the Director for the next Biennale, is there even going to be one?) Are budgetary considerations sufficient justification for showing old work to those of us who have seen it before and really would like to see some new things, not necessarily videos, without having to fly around the world?

Attila CsörgQ showed fascinating delicate kinetic works in his talk at the Biennale Symposium, tremulous version of Plato's solids which lifted and dropped themselves through weights and counterweights. But we didn't get to see these works in the flesh as he was represented by one photograph, a 'key early work' called Slanting Water of two glasses of water on a turntable which therefore looked as if a very strange wind had blown each of them individually. No, he hadn't heard of Daniel von Sturmer. In the foyer of the AGNSW Michael Rakowitz showed White Man got No Dreaming an impressively solid model of Tatlin's Tower built from weathered materials from houses being pulled down in Redfern. This was flanked by two cases full of images and stories telling a potted history of both Tatlin's Tower and Aboriginal Australia. A version of Tatlin's Tower was 'done' as recently as 2007 by Ai Wei Wei as a commission for the Tate in Liverpool. Why remake an early twentieth century utopian building, why not create one for the twenty-first century? Why not show some of Rakowitz's models, made with Middle Eastern packaging, of treasures stolen from the Iraq Museum?

The Gesamtkunst works of Mike Parr and William Kentridge on Cockatoo Island were impressive. Parr's house, an ex-prison, was an onslaught on all the senses and the clever and carefully placed pages of second-rate neo-classical nudes torn from second-rate art history texts thrown on the floor throughout the building seemed wittily to refer to the Bill Henson debate as well as to Parr's own obsession with his body. William Kentridge's exploration of history, memory and techniques for animation were presented vividly in a large dark room as well as on a mirror column nearby that showed drawings projected onto a disc that revolved around the column. Though anamorphic when flat the drawings made wonderful animated sense in the mirror.

I return to the words of artist Pablo Helguera: 'Art has an enormous potential to be relevant outside the art world but for that to happen we need to use the tools of art to create understanding instead of simply promoting the understanding of art'. At bottom this is the type of communication that the artists in the Biennale and Christov-Bakargiev are trying to do, it's just that sometimes the enterprise gets tied up in saying who is 'important' rather than in what they are saying.