A clanging noise during the spin cycle of my washing machine alerts me to something foreign bouncing around with my clothes, alas my mobile phone, left in a pocket, washed and destroyed. Clean, but now another redundant member of life's accumulated objects. In Perth, our streets are dotted annually with council skips filled with yesterday's household treasures, now discarded and destined to become landfill. Our lives are full of guilt-free exit points to send the discarded: drains, sink disposal units, kitchen tidies, rubbish bins and a weekly collection service, even a waste bin on our computer screens!

Items accumulated as facets of our identities are eventually shed like former skins when they are superseded but how often are we made accountable for what happens to once-loved possessions?

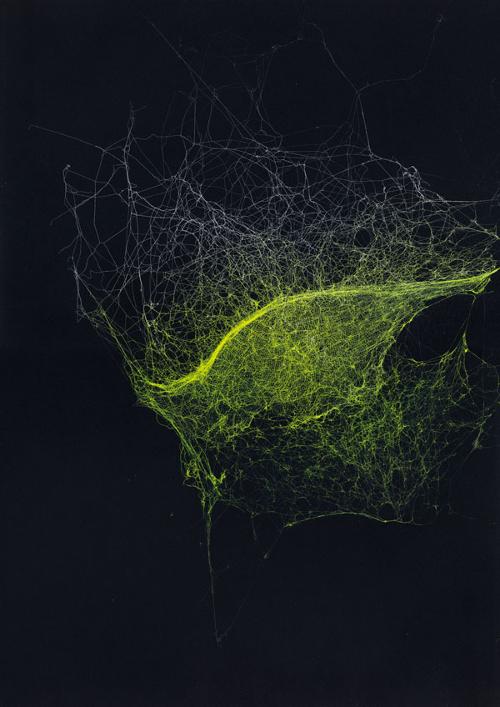

Andrew Sunley Smith's cinema project propels his audience into considering this question. This is the first time his series of international film projects have appeared together as a triptych installation. The work details the destruction of household items suspended and dragged behind a moving vehicle in Denmark, Sydney and Scotland on roads made from a similar surface to the one you find yourself standing on in the gallery as you watch the three films simultaneously. The impact of these projections, each more than four metres high, is increased by the addition of the three varieties of gravel covering the entire floor. Apart from the effect of blurring the lines of corporeality, the gravel allows the audience to experience the sound of their own footsteps as they progress across the space, which also resonates with the sounds from the films. The use of the organic in this work also challenges Land Art legend Robert Smithson's suggestion that a gallery space renders art into an object or surface disengaged from the outside world. The use of the gallery allows Sunley Smith to concentrate our thoughts towards the outside world and our destruction of the ground we tread. The violence apparent in the destruction of the artist's objects evokes the abuse of the environment we agree to every day as we commit our cast-offs out of sight.

Watching the destruction of human-made objects is difficult as they do contain human content. The artist's use of the personal, including a pre-loved chair that could have belonged to your grandmother, a pram minus the babe, and a double bed complete with sheets and pillows, reinforces this message. The black felt curtains adorning the two entrances to the space complete the sensation of entering a cinema for a confrontation with our conscience.

This work is motivated by the artist's personal experience of migrating from England to Australia and the resulting loss or dispossession of humans and objects. His experiences have produced a heightened awareness of our consumptive habits. While he could be criticised for the debris left literally lying on the road during the creation of his work, the artist's practice involves recycling and thus the fact that many of the material victims become works in their own right should be noted.

Like a movie documenting the discarded as they disappear from our thoughts, this film installation forces us to contemplate our actions when we abandon certain people and things in our lives in the process of moving on. This may support the ideas in Clive Hamilton's 2003 book, Growth Fetish, which argues that modern consumers no longer solely consume the utility of goods instead consuming symbolic meanings attached to the objects until that meaning is lost. If Sunley Smith's vehicle represents life's continual forward motion, then as the viewers, we are at the wheel and accountable.