Bigger than Borobudhur? Ever since Brisbane's first Asia Pacific Triennial in 1993, the APT has been the Queensland Art Gallery's best chance to gain recognition for offering something that isn't matched or bettered somewhere else. The undertaking was hugely ambitious from the start, although its origins now seem relatively humble when compared with what's currently on display. The fifth APT is showcased in a truly splendid new building and much of the exhibition occupies prime locations in the old gallery building as well. There is a massive, excellent catalogue. The all-out effort to produce an event on a grand scale is evident everywhere you look.

What you don't see is any of the sincere but awkward ethnic charm that occasionally gave visitors to previous APT exhibitions the sense of getting an exotic tourist experience in their own country. Nor is there an impression that art is being used as a critique of the regime under which it operates. Perhaps it was condescending of Australian gallery-goers a decade ago to seek the vicarious thrills of armchair travelling to lands where poverty and or politics generated art that we wouldn't normally see in Australia. The warm, fuzzy and possibly misguided feelings of solidarity with struggling artists from abroad were once an essential component of the APT's appeal to viewers. Those days seem to have gone. (I should say here that I was a staff member of the Queensland Art Gallery during the first three Triennials, so any misgivings I have about the current one can possibly be dismissed as redundant quibbling about things not being what they used to be.)

The Queensland Art Gallery has worked long and hard to get to this point. Caroline Turner, who originally masterminded the ongoing project, was determined to give it a solidly researched basis, and this aim continues to ensure intense, productive communication between the gallery and the exhibitors. The Long March Project from China and the Pacific Textiles Project indicate how seriously the Queensland Art Gallery is about interacting with participating countries and artists. This time, however, no accompanying conference promoted a public exchange of ideas, instead there were more digestible hour-long infotainment seminars.

A lot has changed in our part of the world since the early 1990s, and the various changes are clearly reflected in APT5. The most significant development is the emergence of China and India as economic superpowers. This was anticipated in the 90s, and sceptical souls might discern a connection between the inauguration of the APT and Paul Keating's enthusiasm for what was then called the 'push into Asia'. A financial slump at the end of the decade, referred to as the 'Asian Meltdown', made Australia's economic relationship with several Southeast Asian countries somewhat less pushy. There was also some realignment in artistic matters. Chinese and Korean artists were becoming major players in the US and Europe. Japanese popular culture was having a global impact on film and fashion. We wanted some of the action, and curatorial focus moved away from Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines (countries we can plausibly describe as our neighbours) towards artists with dealers in London, Paris and New York.

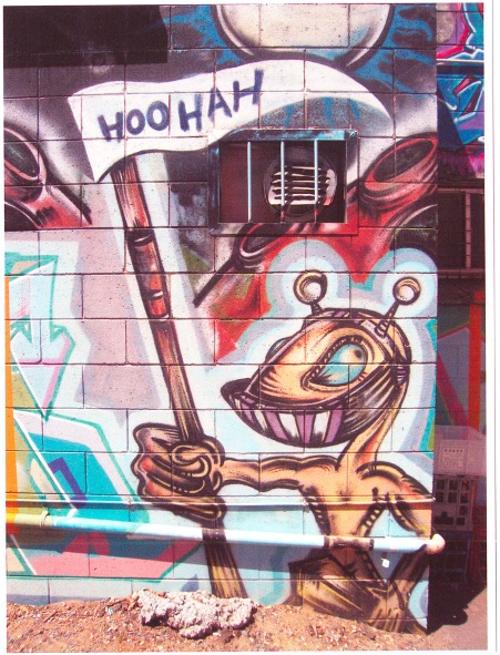

In Australia a gap was emerging between the interests of electronic media savvy youth and the ideals of older curators (many of whom were veterans of the hippie era and the Kathmandu Trail, with a nostalgia for quaint village craft and anything that looked as though it might be somehow spiritual). The growing awkwardness between Australia and Indonesia undermined the friendly interaction between artists, curators and academics in the two countries, and this coincided with a shift in Australian curatorial taste, away from the conspicuously handmade objects of developing countries. One of the most strident works in this exhibition is a floor-to-ceiling mural by Indonesian artist Eko Nugroho called It's all about the Destiny! Isn't it? For this work Nugroho (also represented by some fine, intriguing, small works), simplified and expanded the distinctive Yogyakarta style of furtively subversive pop graphics into stylish public art. It didn't convince me that bigger is better.

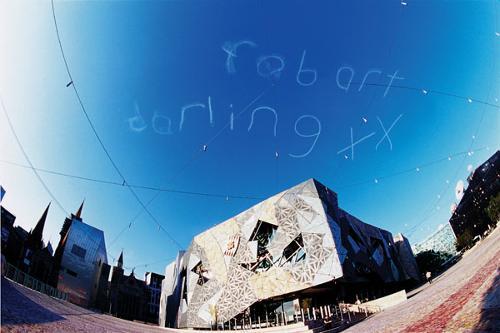

The more spectacular activities of the artists as well as the economies of the Asian dragon nations further north are now dominating our interests. Globalisation has not only had a profound effect on world trade and finance, but has significantly changed the careers of successful Asian artists, the most famous of whom generally work outside their homelands. The current APT is only very loosely arranged by country, and the catalogue simply lists artists alphabetically. Things have come a long way since the planning of the first APT when it was originally suggested (the idea was quickly abandoned) that artists should come to the opening in their national costumes.

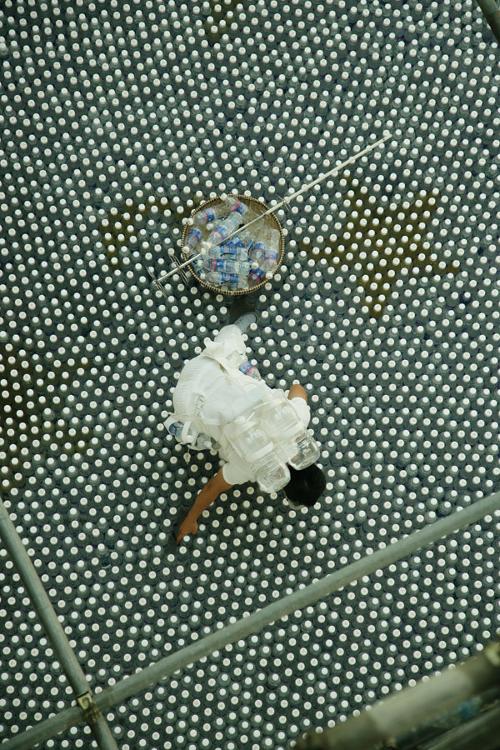

The current exhibition doesn't offer much sense of a curatorial overview and is largely formed around works from the permanent collection (a way of dealing with the logistics of importing a massive show and opening a new building at the same time). It is dominated not by adventurous temporary experiments but permanent museum works made by hip, savvy artists who automatically see the Queensland Art Gallery as part of an international art circuit they call home. The Asia of rice paddies and incense has little connection with them or their work.

For Australians, the Asia of hotel lobbies and frenetic shopping is more real. We rightly feel like bumpkins from a developing nation when we visit the Asian supercities. The new Cathay, the Western fantasy of the exotic East, is dazzlingly embodied in Ai Weiwei's Boomerang, a seven metre high chandelier. The sumptuous tackiness and sheer size of this object are beyond the wildest dreams of Australian hotels and casinos.

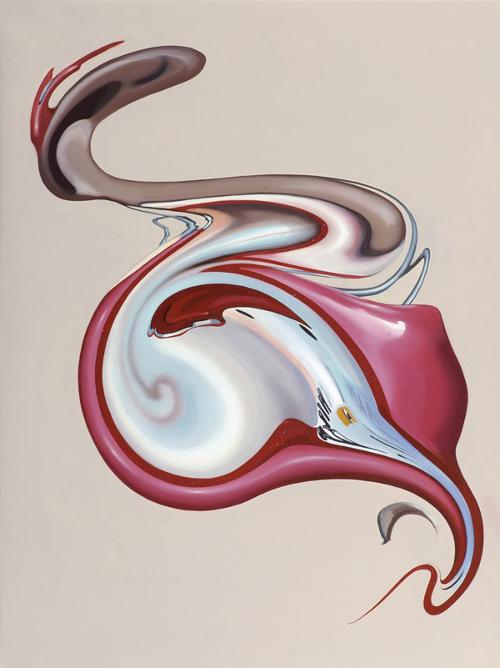

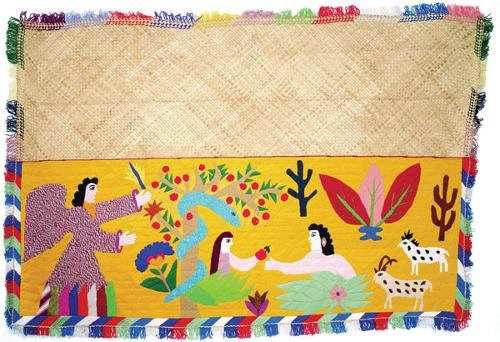

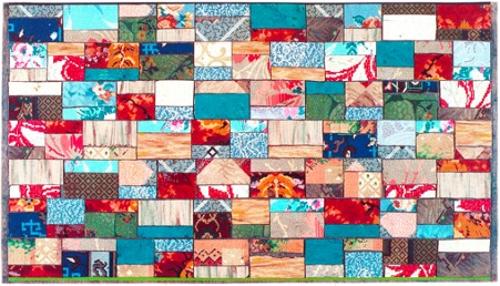

Representation of the Pacific Island nations, some of the smallest populations on the planet, is inevitably somewhat steamrollered by art from the world's most populous countries, which happen to be in Asia. Nevertheless, two of the most memorable components of this exhibition are from the Islands (if New Zealand isn't too big to be counted in with them). The Pacific Textiles Project brings together woven and appliquéd works that might simply be enjoyed as decorative craft, but essays in the catalogue reveal the extent to which they are political statements. Weaving in the Pacific is an ongoing assertion of indigenous culture, and the seemingly innocuous textiles have far more to do with independence movements than is initially apparent. At a time when Australia is intensely and controversially involved in Pacific politics, it might have been appropriate to expand the representation of that region's art still further.

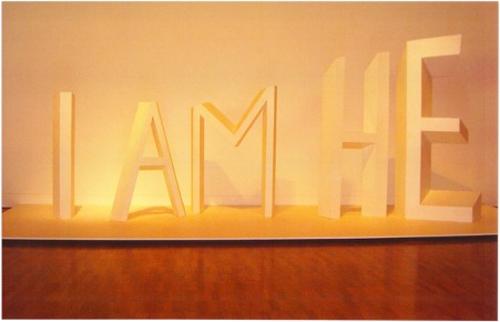

Occasionally parts of the exhibition morph into a scholarly museum retrospective with work that is decades old. This happens most successfully in the mini-exhibition within the New Zealand section of the APT, where the contentious appropriation of Maori motifs by white artist Gordon Walters is examined in conjunction with Maori artist Michael Parekowhai's appropriations of Walters' work.

It isn't always a safe bet to show works by established celebrities. There is a generous selection of sculptures by Anish Kapoor, but only two of them are good. A multi-screen homage to Jackie Chan permits you to watch his entire filmography pass before your eyes at once, but the experience is numbing.

Art triennials and biennials have proliferated in the past twenty or so years, and Brisbane's is an important one because of its distinctive geographic focus. The APT now looks like a big, glamorous international show, and in the past it didn't really. So that's good. My only problem is that big international shows on the tri-bi circuit can become as generic as airport architecture. For a good many years tri-bi art has been a recognisable category. It is generally installation-based and increasingly it involves new media, especially video. The Queensland Art Gallery accommodates it exceptionally well, with generous spaces and terrific equipment. Good installations involve an element of excitement at encountering something that doesn't look like art at all. They encourage a direct engagement with the medium and content without any preconceptions about particular art forms. Because tri-bi art has become a particular art form, an increasingly familiar one, seeing it at its suave best in the APT can be a somewhat superficial experience. There is absolutely nothing daggy in this show (not always the case in the past) yet the unforgiving superiority of the display spaces make the distinction between good and not so good art appear sharper than ever.