Rodney Glick and Lynnette Voevodin are the latest artists to be presented as part of the Art Gallery of Western Australia's Artists in focus program. Their exhibition featured three works from the 24Hr Panoramas series which the artists have undertaken collaboratively across the world since 1999. These three works, filmed on top of a road train truck, aboard the Indian Pacific train and from a desert water tank, have necessitated detailed planning and execution. The exhibition's generous installation encouraged viewers to be open to the expansive scope of the project and to the artists' sense of adventure.

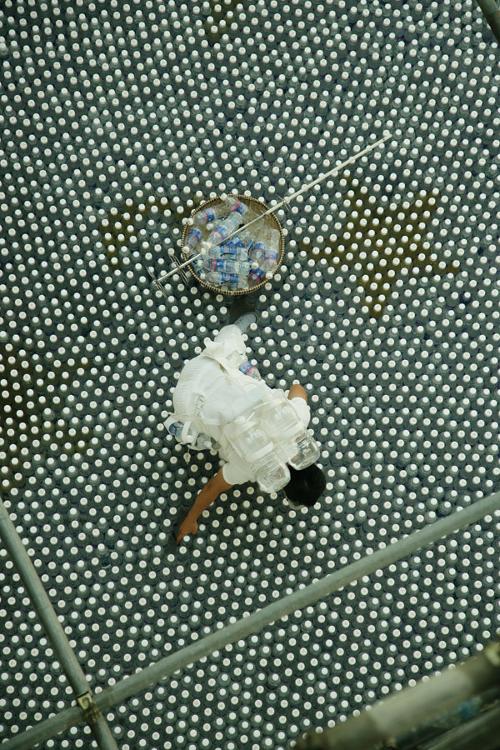

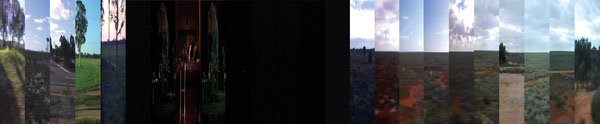

Glick and Voevodin's dual DVD projections are generally constructed using 24 camera locations with each camera recording one hour in a 24 hour day resulting in 24 one-hour parallel streams of compressed video and sound. 24 hours at a location can therefore be viewed in one hour due to this format which combines manipulated space and actual time. The works are splendid and aptly titled panoramas. Their size and proportions (1.6 x 8 metres) give rise to comparisons with the painted panoramas which became popular at the end of the eighteenth century – the IMAX cinema of the day. The splicing of their subjects into vertical sections is also suggestive of pixelated tapestries. Surprisingly, cinematic and televisual comparisons seem secondary.

The methodology for the 24Hr Panorama series was conceived by Glick on one of his regular drives to Kellerberrin, site of the IASKA (International Art Space Kellerberrin Australia) residency program. The title of the first work in the series, Earthquake, refers to the 1968 natural disaster that convulsed the town of Meckering. This work which captures the diurnal and nocturnal rhythms of a lonely stretch of the Great Eastern Highway best expresses the reciprocity between form and subject in the Panoramas. The mutability of the panorama format with its flowing surfaces provides a rich field in which to apprehend the landscape. Phenomena such as vistas framed by car windows, the horizon shimmering in a heat haze and trucks heard before they are seen lend themselves well to translation into this format. Car windows and panoramas both act as viewfinders and the distorting effects of heat are not unrelated to the fractured appearance of a panorama. Sound is central to how we order sensations of duration and distance in our physical and virtual realities. The Panorama series sets the stage for conjecture about the particularities of matter and the subjectivity of time – phenomena which are simultaneously measurable and elusive.

The systematic approach underlying the Panoramas invites pleasurable thoughts about the design of weather patterns, infinite colour variations in nature and favourable conjunctions of events. This potentially totalising effect is countered by the disrupted surfaces of the works upon which our vision lingers. We feel more alive to the glitches in the system through the presence of unexpected elements such as flies buzzing or fleeting cloud configurations. The buzzing resonates with the flickering of the screen and we become aware that, by matching the sections of the Perth-to-Coolgardie water pipeline, the horizon is out-of-kilter.

In Nullarbor, filmed on the train between Perth to Adelaide, the manner in which the temporal and spatial aspects of the experience are folded into vertical sections reflects the processes we use to mark the passing of time. Long journeys are broken into standardised units of sensation such as the regular sway and rattle of the train, the uniformity of passenger accommodation and the ticking off of the stages of the trip. Although both the train and the panorama arguably operate as containers of experience there are reminders that time and space can never be totally regulated. The mobility of the camera and the addition of a radio mystery soundtrack highlight the way the uncertainties of cause and effect subvert any continuum.

The third work, Western Desert, has a less descriptive tone because its subject, the skies of Rudall River National Park, is less amenable to the scopic conventions of the panorama format. Without the motifs of highway, pipeline or railway, viewers are less able to get their bearings and there is considerable dissonance between the lyrical imagery and its soundtrack of daily life in nearby Parnngurr. Accordingly, it feels less dependent on the panorama structure and has a more open-ended sensibility than the other two.

The installation of 24Hr Panoramas meant that the viewing experience was more akin to being in a gallery than a theatre. The sophistication of the projection ensured that it was bright and crisp while the entry to the show was light and inviting. Of course, Glick and Voevodin have long dispensed with the traditional illusionistic devices of landscape painting. In their closely observed and philosophically nuanced exhibition, however, they did retain all the ambition of the panorama.