By all accounts Bronwyn Oliver was at the hight of her career when she took her own life recently at the age of 47.

Well known, highly regarded and immensely respected for her Herculean output of sculptural works, Oliver exemplified the successful steerage of those highly productive yet potentially destructive contradictions that are often found to be at the motivational heart of great art making. She was intuitive yet disciplined, sensitive yet tough, focused yet ever inquisitive, able to display a masterly control of warmth, expression and communication amidst an underlying and at times painful distrust of the relationships that are part of our everyday lives. All this contributing to the development of an outstandingly professional and productive career. Also a committed teacher of young children for 18 years, she eventually had to abandon this deeply rewarding work as the time demands of making her ever more complex sculptures crowded out normal routines, rich and slight pleasures alike.

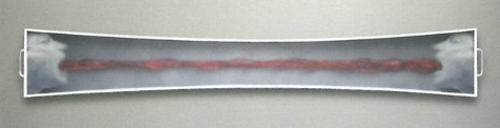

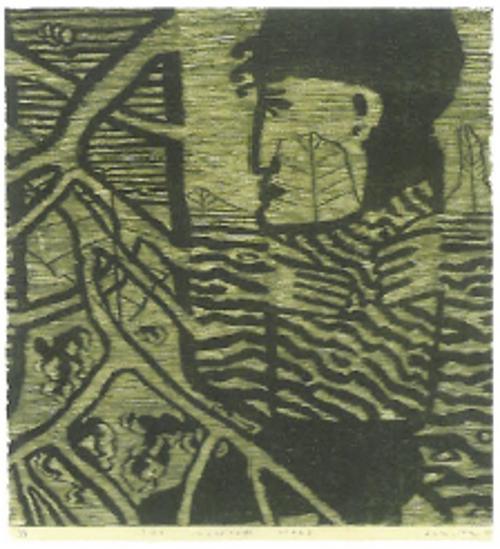

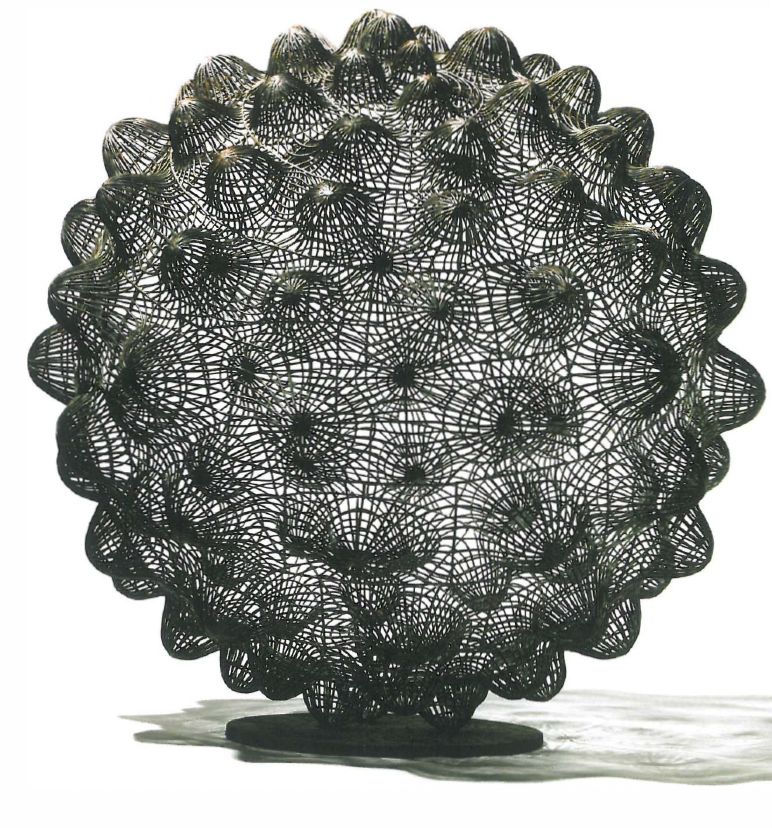

Her delicate fabricated metal sculptures, often rooted in the aesthetic and structural certainty of plant forms, provided continuous inspiration, challenge and satisfaction.

Nature's gene pool itself was extended before our eyes, with the perfect execution of imaginative concept, engineering brilliance, technical and material dexterity and aesthetic resolve. Exhibiting with Roslyn Oxley9 in Sydney and Christine Abrahams gallery in Melbourne, she was pressed, even within the strictest of work regimes, to keep up with the shows and substantial commissions that flowed.

A recently completed work, Vine, reaches up 16 metres from the foyer through atrium space of Sydney's newly refurbished Hilton Hotel. An instantly iconic work, it is recognised as having assisted in turning around the fortunes of this historically iconic Australian hotel. She would also interrupt, if deemed worthy, the order book sequence of commissions to make a small piece for a special occasion or an ailing friend. Her works were eagerly purchased by individuals, by state and national institutions and for numerous public art sites throughout Australia.

The quality of her work was recognised early. Graduating from COFA (then Alexander Mackie College of Advanced Education) in 1980 she was awarded the NSW Travelling Art Scholarship which took her to London to complete a masters degree at Chelsea School of Art in 1983. As winner of the 1994 Moet and Chandon Art Fellowship she sojourned in Europe again. Too numerous to mention, prizes, awards and accolades accrued to her outstanding career right up until her untimely death.

Sydney held two memorials for Bronwyn. One a civil ceremony at a crematorium chapel where mourners hopelessly outnumbered the capacity of the building to hold them, and another, more of a celebration of her life and work, was held in a packed lecture theatre. And Bronwyn was a loner who shunned friends and art world associates alike. At this celebration of Bronwyn's contribution to the arts in Australia, her partner, Huon Hooke remarked how ironic and sad it was that the tragedy of her ultimate loneliness, and now death, had brought forth such a powerful personal and public affirmation of her valued life.

If the loss wasn't so grave, the powerfully inspirational person, the career so clearly only at half-way point, one might feel at rest, to just let it be, recognising the enormous body of work (over 200 pieces) as a bountiful legacy, more than most could hope for. A hero she already is of Australian art, but this alone sells Bronwyn Oliver and those with similar sensitivities and vulnerabilities, passions and convictions, insights, contradictions and afflictions, too, too short. External success, no matter how great, should never stand as the paymaster to early and avoidable death. Rather, calamity of this kind germinates somewhere within the private realm and hardens, locking out good sense and perspective. And it is left to her closest friends and arguably all of us within the Australian art world to ponder what we might have done?

Perhaps I go too far in the writing of an obituary. But you must understand, Bronwyn was one of COFA's own, one of our very best. And much earlier, she was the brilliant little 10 year-old kid I taught in Saturday morning art classes in rural NSW, already clearly destined for great successes, but not this singular failure.