Some people can turn out the light as they leave a room without lifting a finger. Noel was one of these.

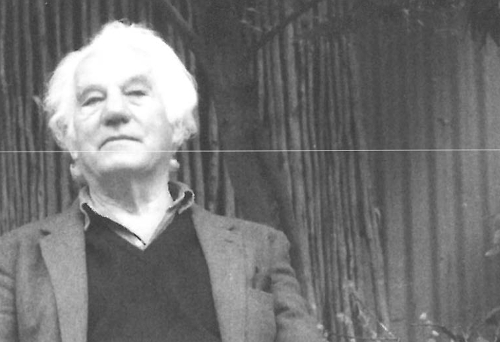

Soon after their expedition from New York to New Ireland was halted in Sydney forty years ago, everyone recognized Noel as a shaman and Liz to be witch. How else might one explain the luxuriant obliquity of their thought, the scale of their generosity and the abundance of their table, on no income?

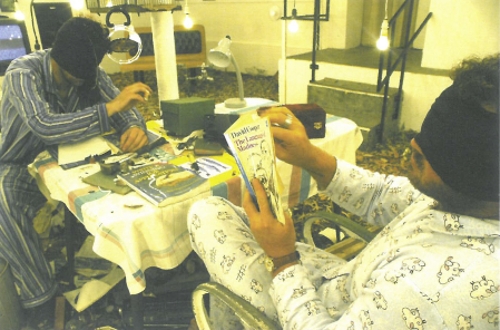

They occupied a ramshackle warren of upstairs rooms shared with Sylvia and the Synthetics, a group of male transvestites contrarily mentored by a de-frocked priest. As visitors we would climb the narrow uncarpeted wooden stairway with its broken light bulb, avoiding a casually discarded nappy, and step into a room with a vast table around which everyone sat eating turkey. Noel would preside, talking magnetically while Liz cast some appalling spell on the wretched Synthetic who had stolen her lipstick.

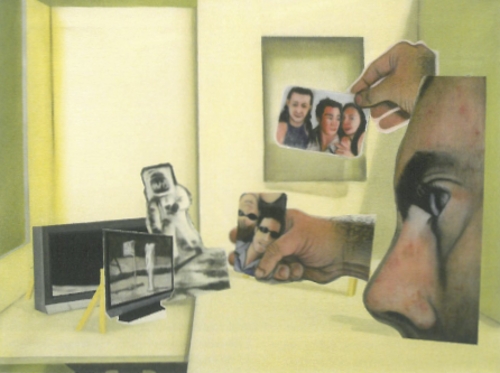

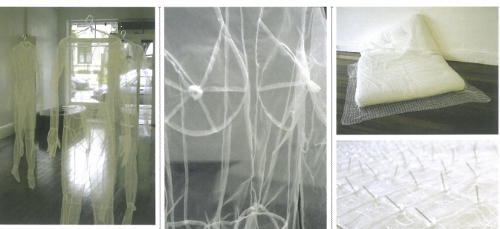

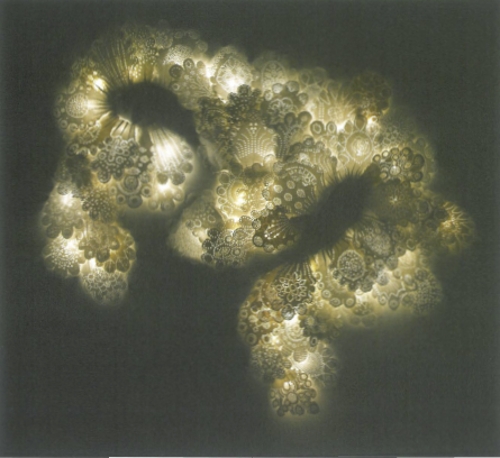

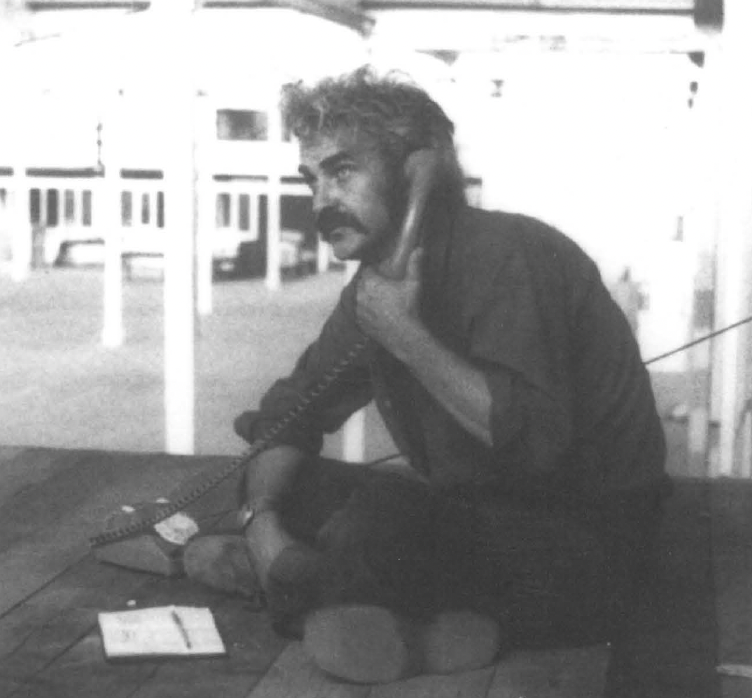

Noel did not, like me, plough the intellectual territory that he meant to cultivate into regular lines of prose. Instead he spun intricate webs of words, their leading strands running in and out of clear sight, intersecting at brilliant points and sliding away into shadowy allusion. His conversation was unquotable, for nobody could ever tell afterwards exactly what it was that he had said. This did not matter in the least, for he knew exactly what he wanted people to do and he would so enchant them that they would immediately go and do it. This is why he became a fabulous teacher, as well as – surprisingly – a formidable administrator. Few people knew that his first tertiary qualification, before he was an actor and an artist, had been in accountancy. It can only have been alphabetic.

Those several of us in Adelaide in the mid-seventies who were ambitious to establish an Australian centre for experimental art found it hard to believe our luck when we persuaded the Sheridans out of Sydney, to come and do it for us. They conjured up two small adjacent houses to live in: one for themselves and the other for their children. As you would. On Sunday mornings they entertained their friends from the untidy throne of a double bed. Ducks would waddle in from the garden, through the open door.

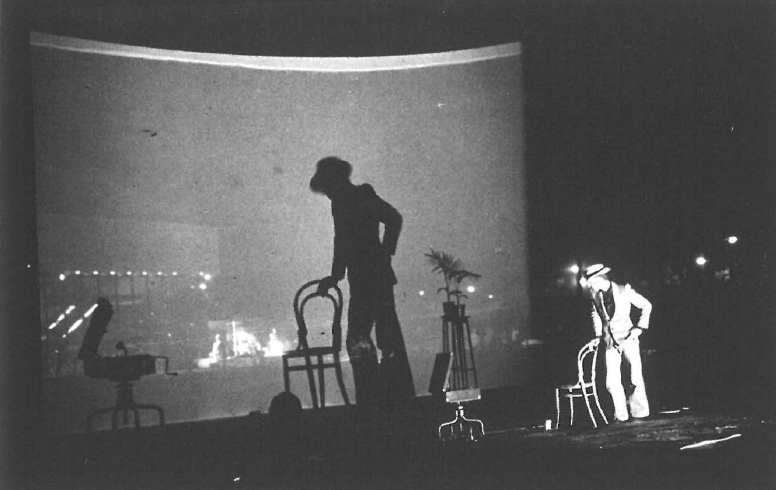

Without the Sheridans it is almost certain that the Experimental Art Foundation would have failed. With them, for several years it must have been one of the most exciting places in the world to be if you really believed that art stands in perpetual need of reconsideration. By the example of his own practice and through the people he attracted as resident artists from all over the world, as well as through the exhibitions he curated and the publications he edited, Noel changed the lives of a generation of young artists and the way everyone thought about art.

It was a task that needed as much plain grit as occult power. The prevailing culture was unsympathetic. There was very little money and there was great resistance. At the launch of an important exhibition the Sheridans donated whisky to serve everyone Irish coffee and were publicly scolded for it by The Australian's art critic, for wasting what he mistook to be public funds. But Noel wasted nothing. When he accidentally put down his new briefcase on a hot electric cook-top, burning two great holes in it, it became a work that he wryly entitled The case for keeping & . He gave it to me, and I am now greatly ashamed to admit that I have lost it.

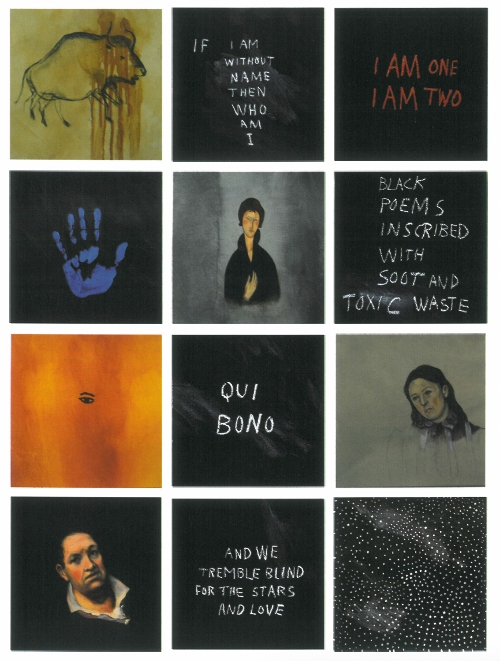

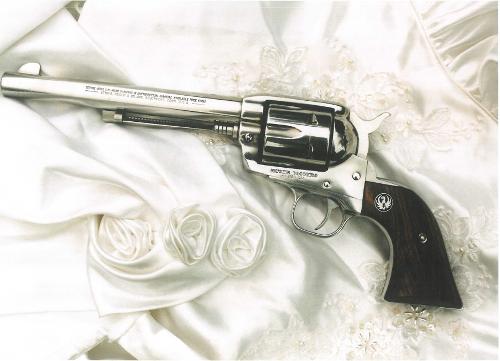

Everyone remembers his wearing of the green. A green suit, green shirt, green socks, green shoes, green pen, green ink. He was primarily a performance artist, ambivalently citing the example of his father, who had been a pantomime dame. He was besotted with James Joyce. Later in Perth he would give readings from Finnegans Wake with Patrick Healy, and years later again from Dublin he would go to New York to read the entire book onto compact disk. He wrote beautifully, as everyone fortunate enough to have a copy of his 2001 self-portrait called On Reflection, will acknowledge. He returned eventually to painting, and prolifically filled three galleries in the retrospective that he mounted in Dublin in the same year.

Here is a fragment of his writing, about New York as they had known it in 1964.

It was time to check out the lead to the landlord who paid cash to have apartments on the Lower East Side painted out. &

He showed me the rooms, brushing past a diminutive couple who lived there, avoiding conversation with them. Yes, he did know their rights, repainting every seven years, that's what he was doing. Of course it would be done perfectly. 'This is the painter.' They surveyed me with narrow eyes that had known many bitter disappointments.

'He's the painter?'

'Yes.'

'We're entitled to a real painter.'

But – although this would cause Noel no distress – I am now out of chronology, in both directions. He left the Experimental Art Foundation to go back to Dublin, partly because he could not resist the challenge to revive a moribund Irish National College of Art and Design, and partly because there was – or so he assured his disbelievers – no more that he could do.

After Adelaide his life was spent in irregular passages between Dublin and the Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, where he tried to cajole even resistant Western Australians into thinking seriously about art. Two memories from PICA are indelible. One is the expedition that he made with Liz to the far north, from which they returned to Perth with a gigantic truck of red sand to spread on the gallery floor, and a group of Aboriginal artists who spoke no English at all and would live on this sand wherever it was spread. They had never visited a city, but were unselfconsciously and powerfully disposed to show some wholly authentic aspects of an altogether different way of life.

The other brush with something that is both universal and unexpected was the heart attack that Noel suffered when he left his office for a few minutes to visit a nearby doctor, because he felt unwell. The ambulance that was summoned turned out to be the only one in Western Australia equipped with a defibrillator; and he lived. He was placed briefly in a recovery ward, but then removed by the nurses because the stories he told about death and dying when he sat up in bed put the stitches of the other patients at risk.

On 12 July 2006, back once again in Perth with his family and an unstoppable cancer, in the midst of reconstructing a lost performance work and building a new painting studio, he sat up in bed with his laptop to write emails. But instead of doing this he lay back for a moment and died. The last words often attributed to James Joyce are: 'Does nobody understand?' Despite the respect that Noel had for the master I do not believe that this is what Noel would have said. If that thought had occurred to him, he would have started to explain.

Liz reports that he went into the fire with his book and his sunnies, in the green suit that he wore in Adelaide.