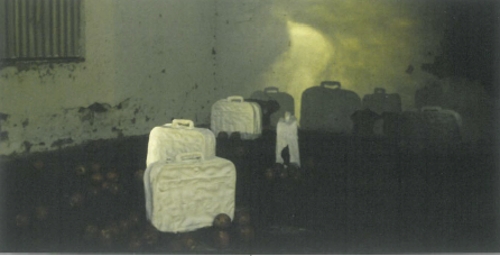

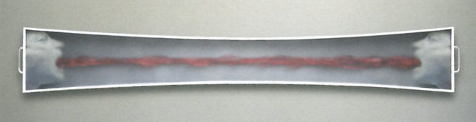

The elusiveness of Kim Demuth''s new work starts with wondering how they are made. Demuth makes wall-mounted boxes with transparent fronts of etched acrylic. Inside, semi-sculptural forms loom in and out of darkness. They could be photographs of pale bodies and body parts moulded into sculpture; they could be paintings or drawings; they could even be holograms. Not only are they structurally fascinating, it's also difficult to visually get a grip on them – the closer you get, the more indistinct the subjects. The works are also literally dark– unlike much of his earlier work, Demuth no longer incorporates light sources into his boxes.

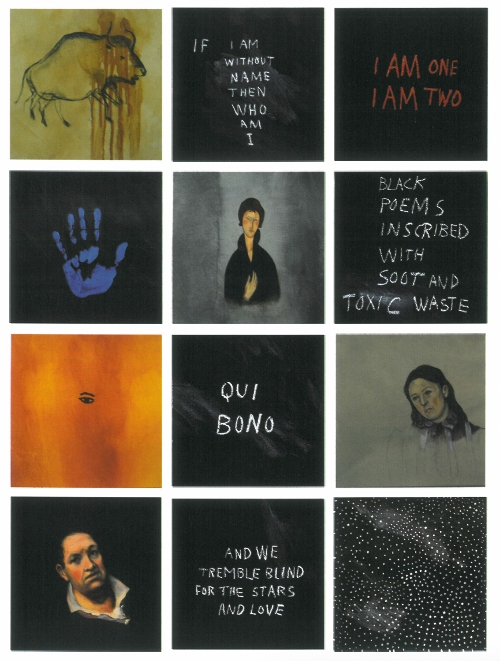

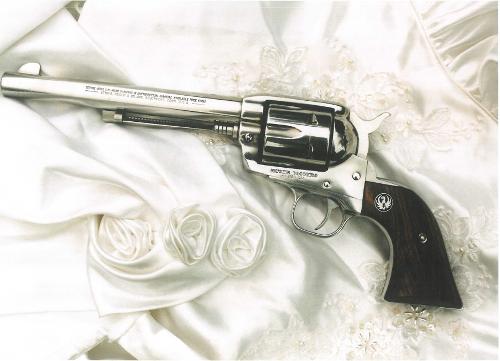

For Demuth, the enigmatic is more than a style. Demuth deals in uncertainty, asking questions about the human experience of the body which have no easy answers. One such question is whether our bodily experiences, particularly our pain, serve any purpose. Demuth portrays moments of human abjection – pain, purging, violence, death, despair. In making them into beautiful luminescent objects, almost like religious icons, Demuth hints that our suffering is meaningful, that the abject body is the locus for our defining moments, the best and worst of man from murder to martyrdom. For example, Noise, a dismembered ear hovering in darkness, simultaneously evokes Jesus (who healed the ear of one of his arresters), Van Gogh and Chopper Read. Here the abject body hosts narratives of forgiveness, despair and derangement. Ultimately, however, this layering of historical references fails to give us any insight, other than that the abject body is a shared experience. Demuth's works transfix rather than change or move us.

This ambiguity is particularly puzzling when we consider that Demuth studied the works of Goya on a recent residency in Barcelona. In some of his bleaker works, Goya depicted the human body brought low through violence, and this is often held up as a masterful recognition of every human's true barbarity. Where Goya pointedly asked the viewer 'Is this what you wanted?' Demuth's works fail to horrify or shock us. Instead his works seem cryogenic, deferring confrontation, cordoning off pain and isolation behind cloudy acrylic. It's as if he entrusts these moments of abjection to a future when someone else will be able to understand and cure our condition.

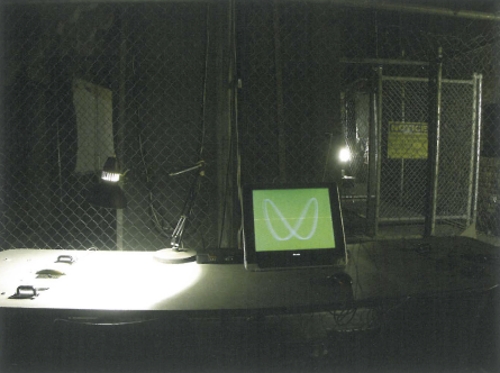

Demuth grapples with another big question – is it possible to overcome our physical isolation even though our corporeal experiences are disparate? Demuth portrays the difficulty, even futility, of communication between isolated bodies. God my God, a work where enclosed, mouthless faces attempt to communicate via antennae, examines our potential failure to make known private fear and pain in an increasingly mediated world. Demuth's sacred iconography, such as his references to ascension or his portrayal of the death of the Pope, evokes the tension of constantly reaching towards God without ever touching. Again, Demuth posits no solution to this endless struggle. In the static scenes inside his works, there is never a hint of movement or change, never a suggestion that the gap can be bridged.

Just as the way Demuth constructs his objects tantalises yet remains unknowable, the artist invites us to ask the big questions about being human without the promise of reply or revelation. While the works raise fascinating, important questions, ultimately they fail to suggest an answer or a way out, preferring mystery over enlightenment. Perhaps the secrecy of his work is meant to double the baffling questions of existence, questions about what it means to be alive and embodied. The artist knows but the viewer is forever in the dark. There is only so long that this self-sustaining elusiveness can hold our attention and in the end it simply becomes too easy for us to walk away.