For Rumi, death had nothing to do with going away. The thirteenth-century Sufi mystic and poet described it as a coming together. The outpouring of love for Hossein Valamanesh in the hours and days following his unexpected death in his Adelaide home on Saturday 15 January confirm what we’ve suspected all along, and what Hossein deeply understood— Rumi was right.

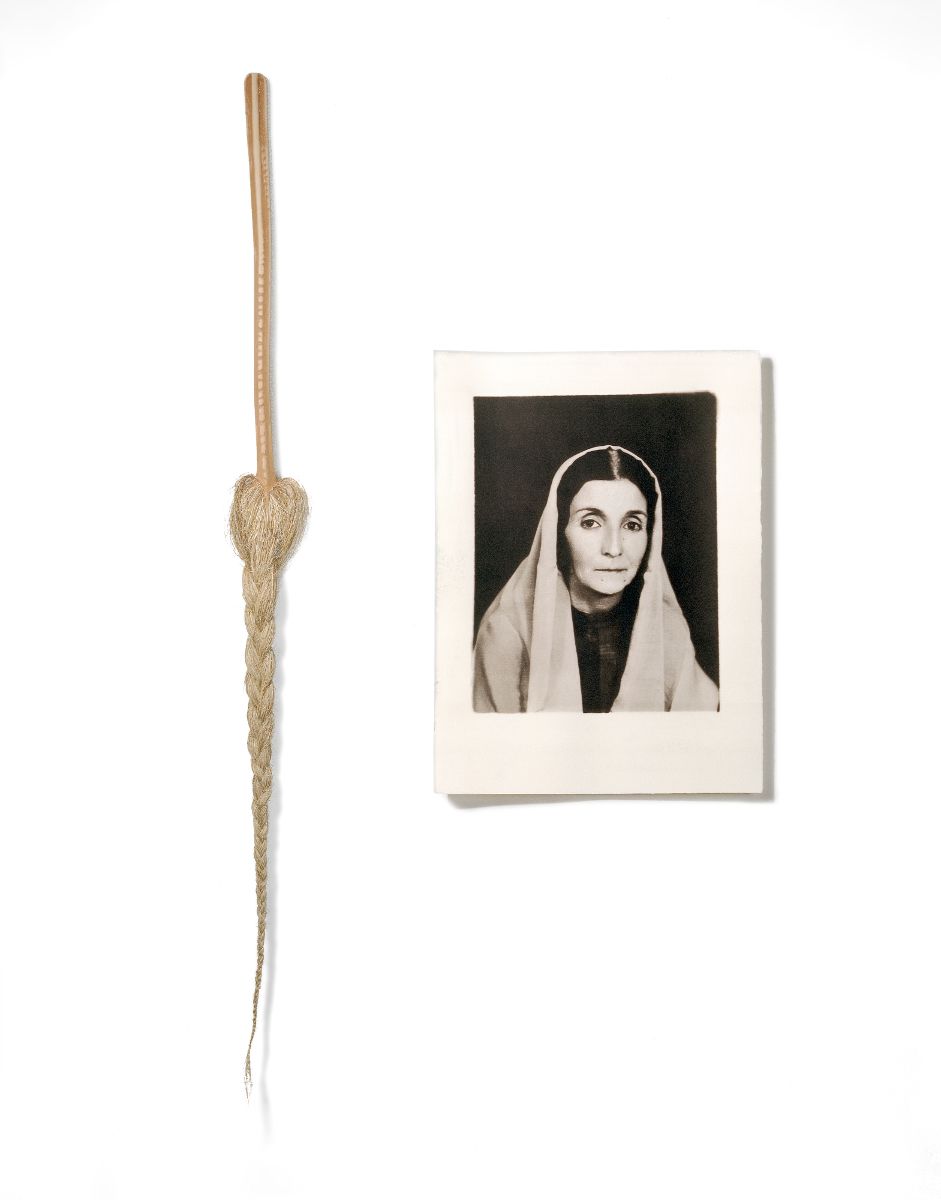

Soon after arriving in Australia in the early 1970s, Hossein was drawn to the desert, to Papunya, and there he sat among the Aboriginal artists who were making Australian art anew—not realising that he too would reshape the art history of his new country. Settling in Adelaide in the mid-1970s, he met his wife and life-long collaborator Angela at art school. He later remembered being captivated by her long plaits. Woven tresses would return time and time again in his work, perhaps most memorably in Homa from 2000, in the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA) collection, in which a palm leaf is transformed into the braided hair of his Iranian grandmother and pinned to the wall alongside her photographic portrait.

Adelaide’s Experimental Art Foundation staged Hossein’s first Australian exhibition in 1977 and his work graced the very first cover of Artlink in 1981. In 2001 Sarah Thomas curated his survey exhibition for AGSA, by which time he had already established his singular and poetic vision. By this time, too, his work was represented in national and international collections and exhibitions, along with public art commissions, all supported locally by Bonython Gallery and then Greenaway Art Gallery and GAGPROJECTS. His Wakefield Press monograph titled Out of nothingness, written by Mary Knights and Ian North, followed in 2011.

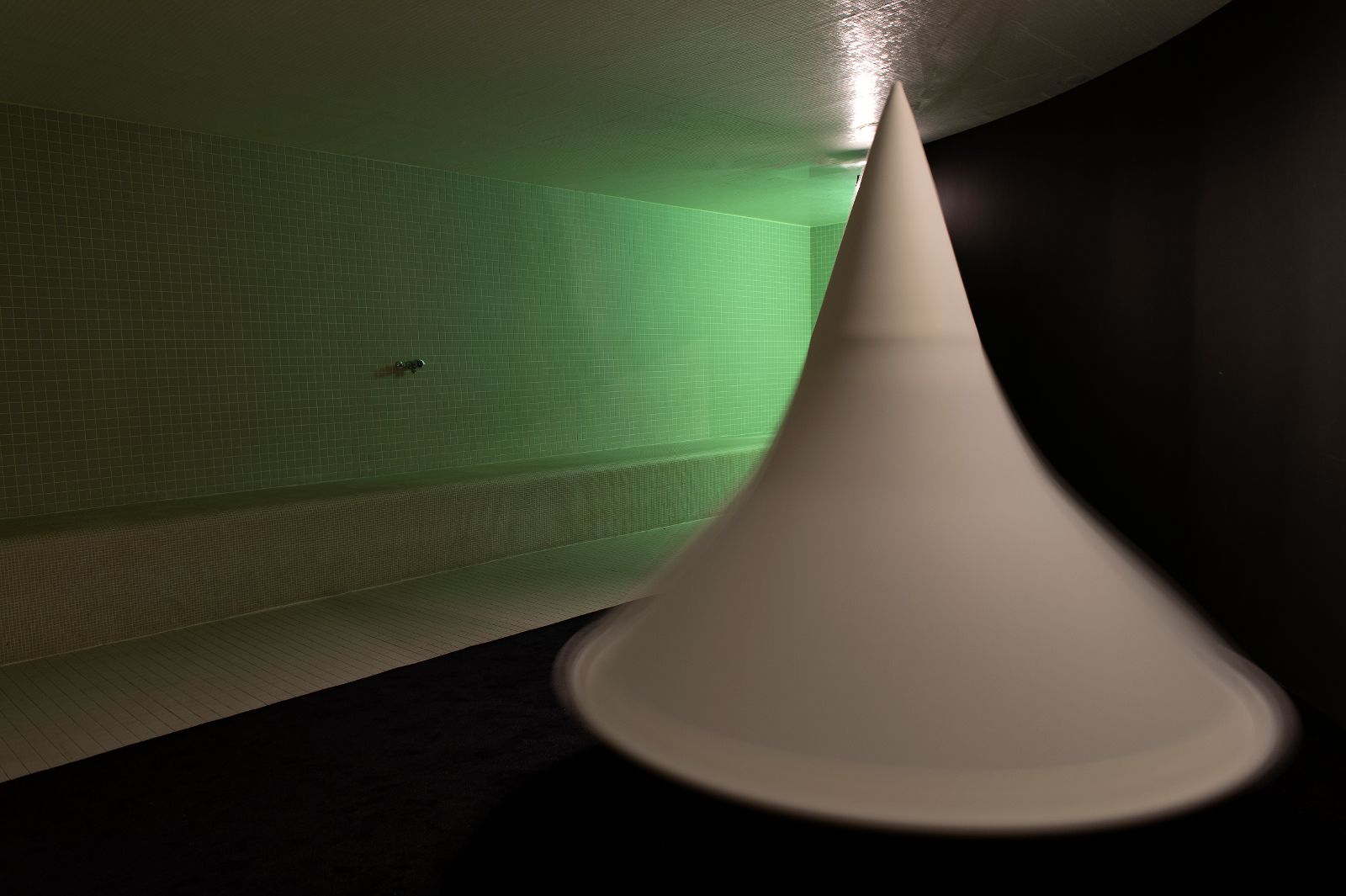

His is an art in which often modest materials speak. They are transformed into inclusive ritual spaces—so democratic that more than 70,000 people came to AGSA to see his 2001 exhibition. The resonance of this exhibition led to Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art staging an abridged version and to their acquisition of The lover circles his own heart (1993). This work, with its eternal spinning inspired by the ancient Sufi dance of whirling Dervishes, would provide a wellspring for future projects including Puisque tout passe (This too shall pass), Hossein’s current exhibition (until 13 February 2022) at the Institut des Cultures d’Islam in Paris, where a version of the work whirls day and night in the hammam.

Each day in Adelaide, the arboreal offspring of The lover circles his own heart turns, drawing in audiences and creating the meeting places of the future. Meet me at the spinning tree, they say. Titled After rain (2013), this kinetic installation made its debut in Andrew Bovell’s acclaimed play When the rain stops falling, for which Hossein was set designer working closely with Chris Drummond. It later featured in AGSA’s 2013 Heartland survey exhibition of South Australian art, alongside collaborations with Angela and their filmmaker son Nassiem.

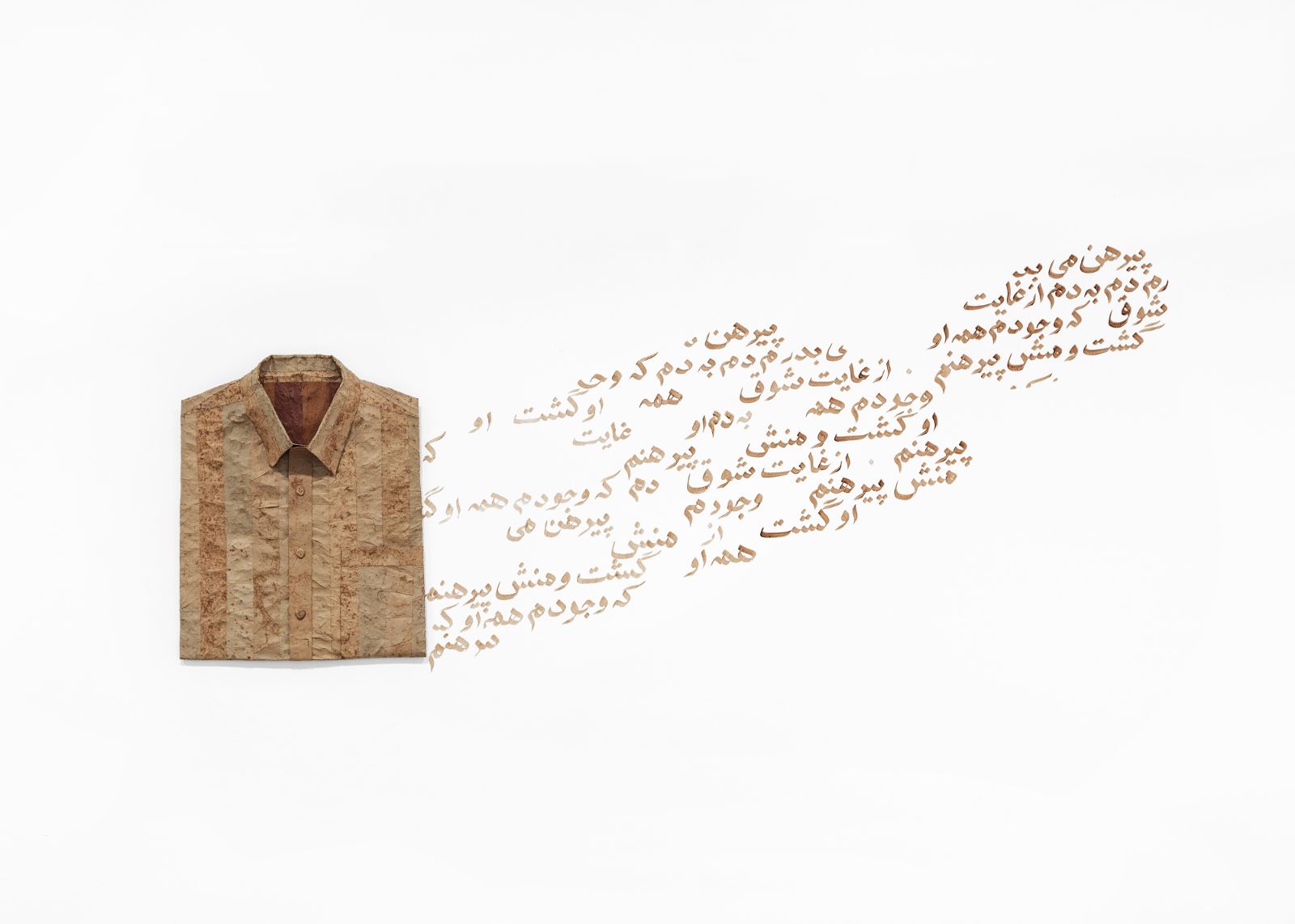

Near the turning tree at AGSA, Farsi script painted directly onto the gallery wall writes a shadow in the shape of a figure. The shadow emanates from a folded shirt made entirely from lotus leaves. The text —from a Sufi poem, painted by Hossein several times over now in the life of the work of art—translates as I tear my shirt with every breath for the extent of ecstasy and joy of being in love; now he has become all my being, and I am only a shirt. Poetically cryptic, the words suggest that by loving another we lose, and find, ourselves.

Decades and decades of work have emerged from Hossein and Angela’s entwined Adelaide studios and in just a few weeks their most recent, and some of their earliest, works of art will feature in the 2022 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Free/State, curated by Sebastian Goldspink. There we will find Hossein, to requote Rumi, forever whirling, out of nothingness, scattering stars, like dust…