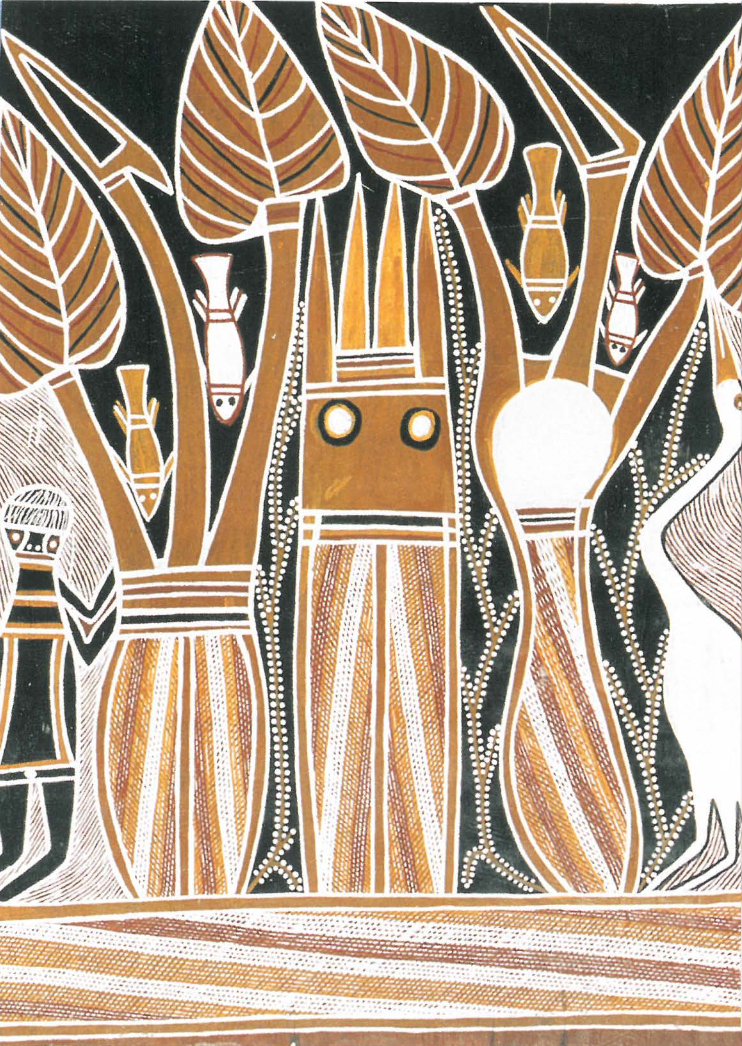

The inclusion of bark paintings from Ramingining in the 1979 Sydney Biennale was one of several defining high points in the lengthy career of Arnhem Land painter and sculptor David Malangi. As an artist whose working life spanned four decades, his work was seminal to the transformation of Arnhem Land art from its isolated location and largely 'curiosity' status into the dynamic position that it now holds within the complexity and diversity of contemporary Australian artistic expression. From the earliest part of his career starting on the island of Milingimbi and through the 1950s and 1960s when he and many other Aboriginal families re-established residency on their traditional land on the mainland, Malangi's works were avidly sought by early collectors and major public collections in Europe and Australia.

It was also from a painting of this period that the key figurative elements for the now discontinued one dollar note was taken. And though the artist himself was only belatedly recognised as the originator of the designs, Malangi's figures represented a critical, symbolic component in the re-assertion of Aboriginal political and cultural identity that developed nationwide during the 1960s.

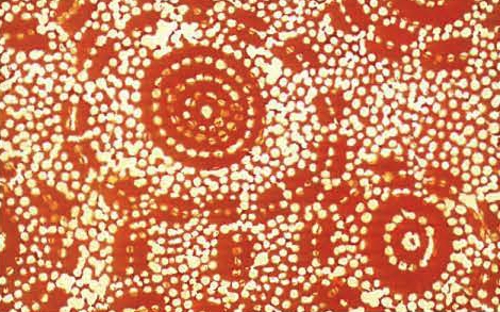

Devoted to the re-establishment of control over his Djinang land at Yathalamarra and the respect and care for its sacred places, the consistent inspiration for his artistic output never strayed far from the Djinang ancestor being Gurrumirringu and the Dhuwa moiety Djan'kawul Sisters. The intensity of detail in Malangi's Gurrumirringu paintings belies the relatively small dimensions of most of his output, but in the interplay of flora and fauna and figurative elements few Arnhemland painters match the deftness, complexity and emotive intensity that the artist achieved in his major compositions. Eschewing in most of his work the intensity of cross-hatched infill that provides a formal but essentially emblematic framework for much Arnhem Land art, Malangi's animated narrative depictions contain tightly packed detail set out on a plain background. His compositions engender a rich and continuous visual flow of sacred and secular information which, replete with keen seasonal and botanical observation, introduce the viewer to the depth and interplay of the Dhuwa moiety and Djinang sacred iconography. With the profusion of detail included in his best works, reading Malangi is somewhat like approaching the work of Giotto and other Pre-Renaissance painters where the lack of a clear hierarchy requires a more engaging interaction by the viewer.

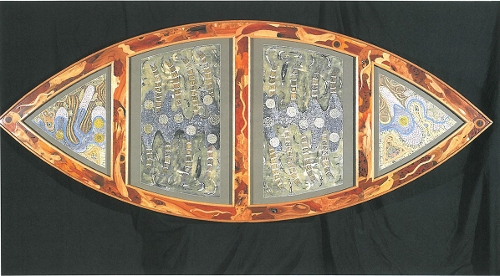

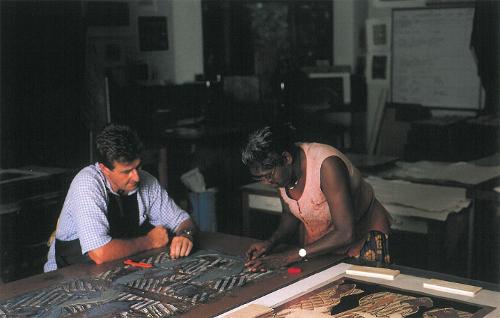

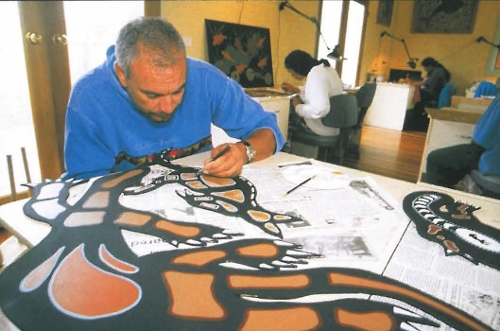

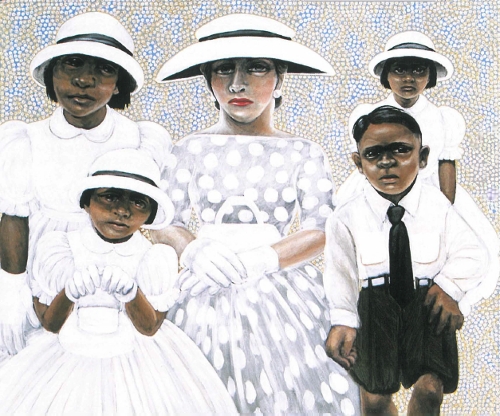

This engagement with the interplay of surfaces and outside and inside meanings was to become a major influence for the artist Lin Onus, who, in developing close artistic and personal friendships with several artists in central Arnhem Land, became inspired by the fusion of formal and psychological dimensions perfected by Malangi and other senior Arnhem Land artists. As a storyteller (as opposed to painter) the artist also had few rivals in his retelling of the great events surrounding the ancestral beings of his country and, in his social encounters with artists in other parts of Australia, despite language and cultural divergences, Malangi was an animated conversationalist. This was demonstrated in particular when he attended the 1979 Sydney Biennale where his work was included along with fellow countrymen George Milpurrurru and Bunguwuy by the Director Nick Waterlow after a proposal by the Ramingining Artists' Cooperative Co-ordinator Peter Yates.

From the perspective of the ensuing 20 years when Aboriginal artists have become such a central part of the Australian art scene and redefined core areas of Australian cultural identity and its diversity, Malangi's contribution and presence should be recognised as a major ground-breaking part of the subsequent changes.