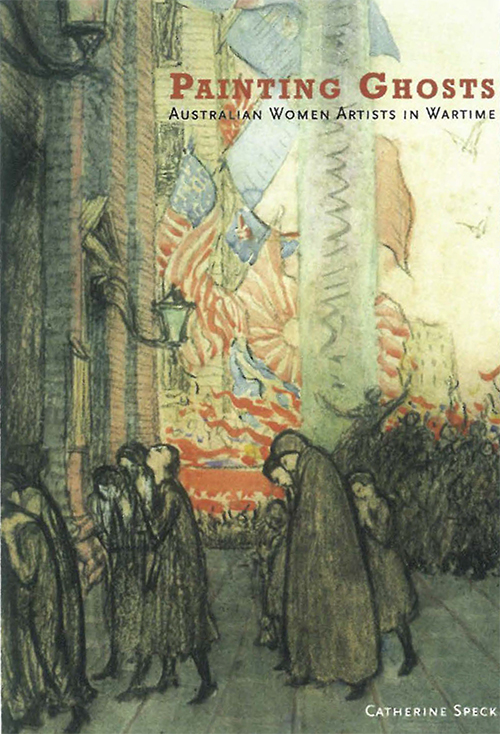

It has been argued that war is 'the quintessentially gendering activity'. Men take up arms, while women provide support from the home front. Thus war is not only gendered, but spatially ordered. Catherine Speck's Painting Ghosts argues that, while not called upon to kill, Australian women's experience of war, and its reflection in art, is no less worthy of consideration than men's. Moreover, the breadth and quality of the art reproduced here proves incontrovertibly that their contribution must not be elided from serious study.

Painting Ghosts also extends recent arguments over the shaping of Australian national identity through war. The leading scholars in the identity debate (Richard White, Miriam Dixson, Neville Meany, John Williams et.al.) though differing in the breach have each decried 'single strand narratives' of nation formation. Speck's method is relevant and up to date, and in her account we find a nuanced argument about women's contribution that doesn't just slot them back into the mainstream but reveals both structural and ideological reasons for their exclusion and emphasises their agency in overcoming these barriers.

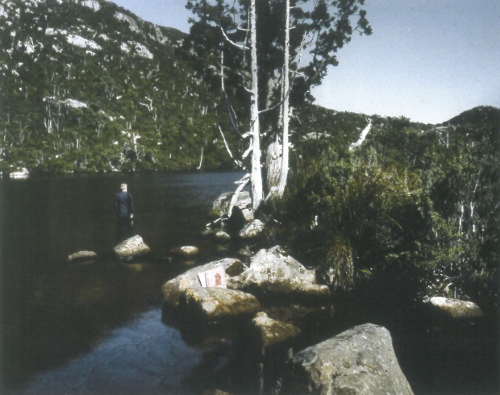

In her introduction Speck argues that war called women into public life and placed sudden demands on them to master new medical, agricultural and industrial skills. Thus their move from private to public life – from 'maternal' to full citizen – was sealed, despite later backlashes. But how was this historic shift recorded? In the First World War no Australian women were 'officially' employed as war artists. Nonetheless, a handful were already at the French front, like Iso Rae in Etaples, and Evelyn Chapman in Normandy (just after Armistice). Here Speck pays particular attention to their representations of the 'devastated landscape'.

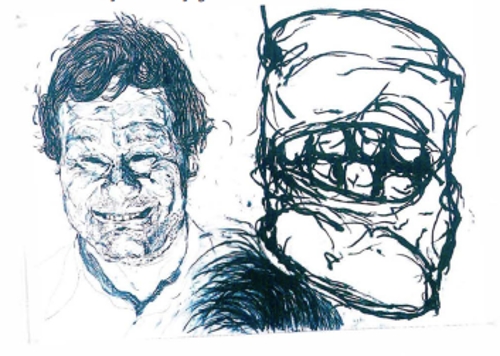

In the section on the Second World War, Speck gives us not only fascinating readings of the art produced by the three official women artists, Nora Heysen, Sybil Craig and Stella Bowen (in England), but she also gives account of the struggles they had working in the unfamiliar culture of the military. It seems that even when the military finally commissioned women as official war artists, they laboured under different expectations than their male counterparts, and their projects were more tightly stage-managed, by 'minders' like John Treloar, director of the Australian War Memorial.

The book's value to scholarship is that Speck's analysis brings together art by Australians and women of Allied nations, it covers both 'official' and un-official representations of war, and it incorporates images from all registers, from oil paintings, to Australian Women's Weekly magazine covers. Thus we have a valuable, comprehensive and 'multi-voiced' view of how women artists reflected on seismic re-orderings of gender relations that war has wrought over the last century.