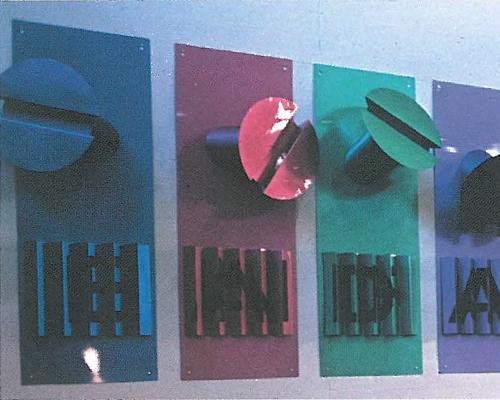

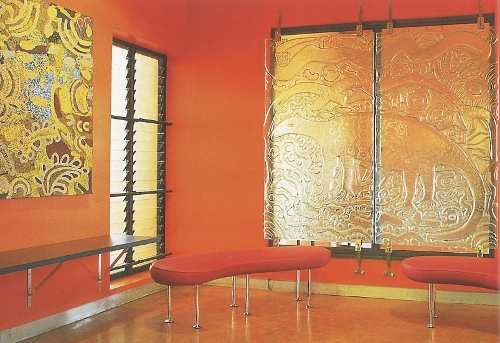

Immediately striking, on entering Perth and Singapore-based artist Matthew Ngui's site-specific installation at the Contemporary Art Centre, is a floor to ceiling feature panel, reminiscent of the interior/exterior feature walls that characterised architecture of the 1950s and '60s. Reiterating both the circle motif and bluish colouration of his 2002 Berlin exhibition, Ngui has covered the freestanding divider with an arrangement of blue slices of PVC pipe. The adjoining space is strewn with vertical, white-painted and black-daubed poles of PVC stormwater pipe, resembling a synthetic forest of simulated scribbly gums. Viewers - aware of the presence of two surveillance cameras - are nevertheless inclined to linger in this space, examining at close quarters the indecipherable black squiggles and fragments of letters and communicating with one another through the pipes' apertures. Far from an arbitrary distribution of upright poles, Ngui manipulates and directs the progress of the viewer, with his highly considered placement of these barriers.

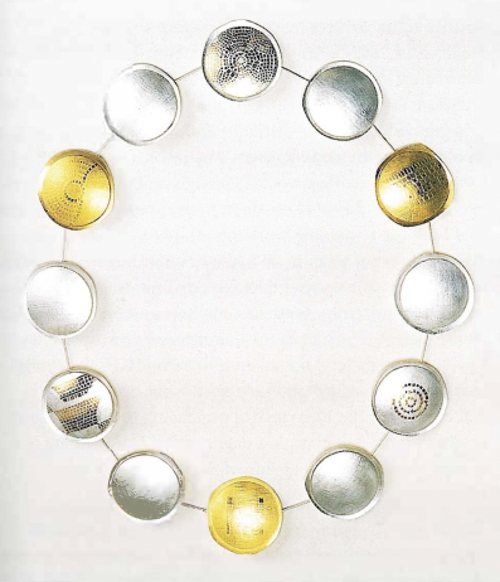

Nearby, a two-dimensional construction of pieces of plywood, taped onto the walls and floor and stretching the entire length of a room, provides further incentive to hover. When this apparently haphazard arrangement is viewed from a (helpfully) designated vantage point, the anamorphic image assumes three-dimensional form, becoming recognisable from the viewer's perspective, as a 'chair.'

Art historically speaking, anamorphic images have long been employed to amuse, bemuse and in the case of the distorted skull in Holbein's The Ambassadors, as a memento mori. Less well known is Jean Francois Nicèron's (1613-1646) anamorphic fresco, which covers an entire wall of the convent of SS. Trinity dei Monti in Rome. As the viewer traverses the length of the corridor, Nickron's extraordinary depictions of Saint John on Patmos and San Francesco di Paola as a hermit are miraculously revealed.

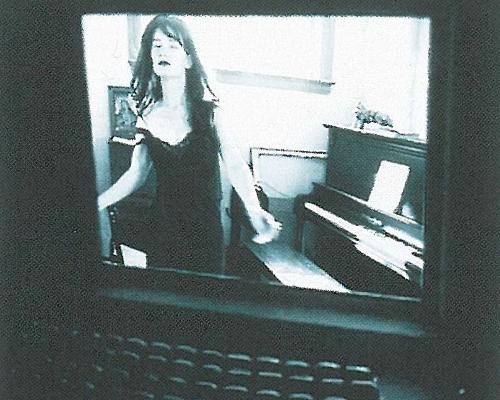

Ngui seamlessly draws together these disparate threads in the rear gallery, where the cold rigidity of the pipes is transformed into a wall projection of readable black text on a seemingly soft white background, through which people continually and remarkably weave. It is a moment of surprise and revelation, as viewers accustomed to the habitual passivity of their role, become aware of the extent of their own inadvertent complicity in an artistic dialogue. An adjacent video monitor shows Ngui, seated on a chair. Rising, he leans against and then places his foot through the deceptive solidity of the seat. Not just metamorphosis then, but anamorphosis as well.

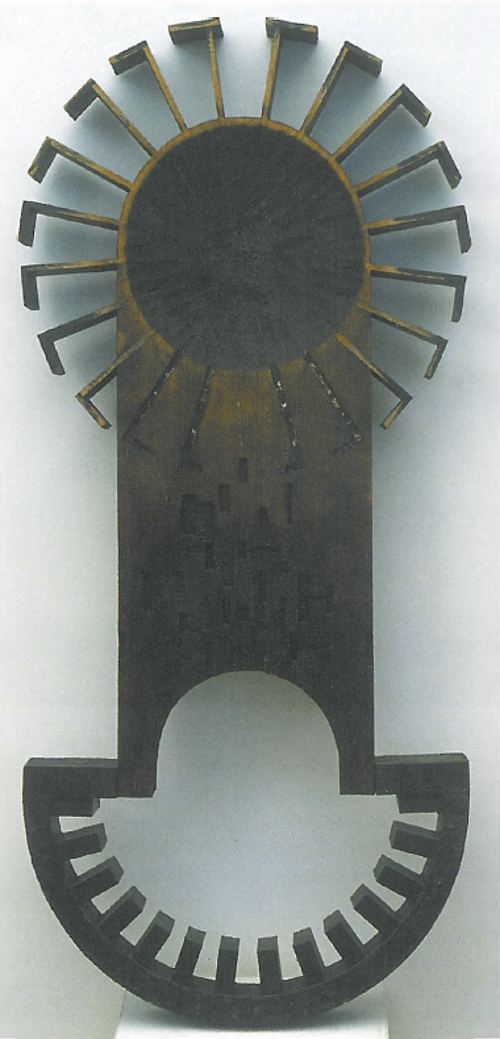

Three hundred metres of grey tubular pipes snake their way along the walls of the gallery, erupting into pipe organ-like forms in the rear gallery space. From these, the steely sound of chimes - one of three separate audio components developed in conjunction with sound artist Rob Muir - intermittently emanates.

'A chair is an implement upon which one can rest one's body, by placing the buttocks upon the seat and the back against the back support&' reads the opening line of Ngui's wall text. The statement appears unequivocal, incontrovertible, yet as Ngui so eloquently demonstrates a 'chair' may not be a chair at all. When is a chair a chair? In his text for Ngui's Berlin exhibition, Brazilian writer Ricardo Muniz Fernendes asserts: '&the main function of this space is to move us to think. It is not a place for certainties but one of illusions, questions and possibilities.' Similarly Ngui, in this thoughtful and thought provoking installation at CACSA seems to consider, that not only are there limits to perceived knowledge but that there are many ways of seeing. 'Truth' or 'reality' can be manipulated with frightening ease and the implications for the wider technological world are unmistakable and manifold.