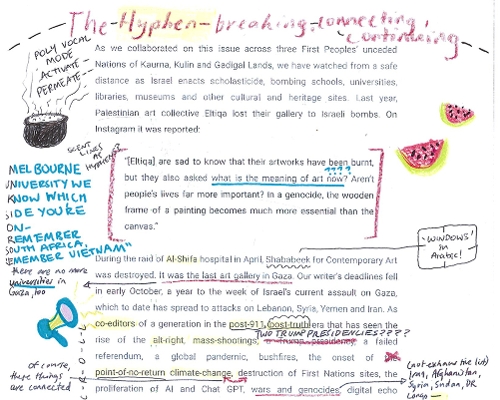

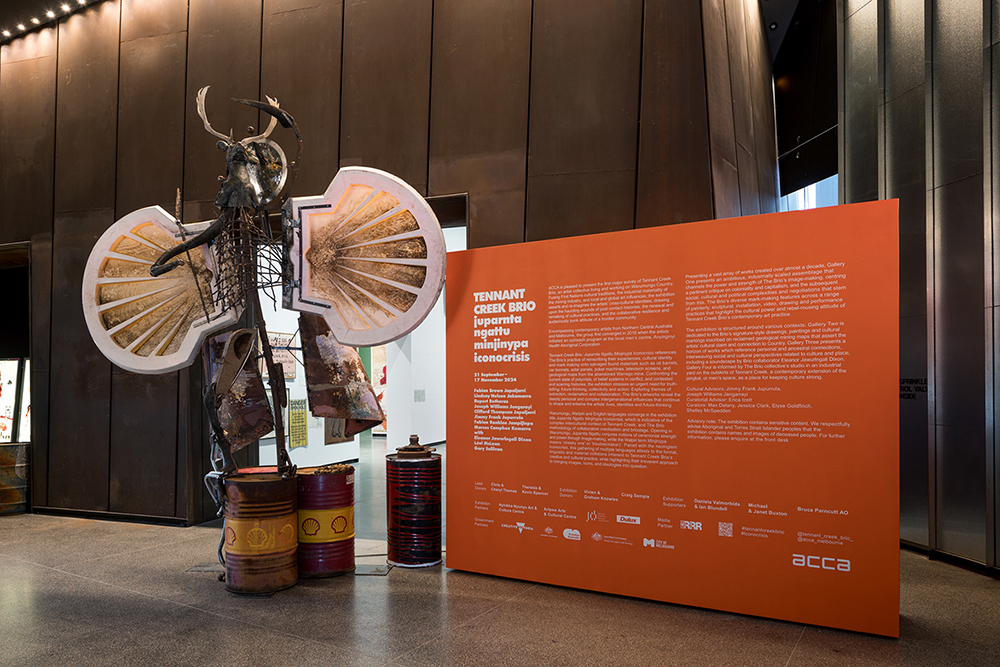

The visit of the Tennant Creek Brio to Naarm coincided with two major cultural events – the Pharaoh exhibition at the NGV and the AFL Grand Final. The Brio anecdotally and excitedly referenced both titan phenomena in the lead up to their first major survey Juparnta Ngattu Minjinypa Iconocrisis at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), in itself a leviathan spectacle.

Brio artist Jimmy Frank Juppurula described the survey as being ‘like the grand final for us’, while the Egyptian god Horus made an appearance in the 2020 titular work by Fabian Brown Japaltjari, long preceding the visit of the Pharaohs. One of a suite of works first presented in NIRIN, the 22nd Sydney Biennale (2020), Horus is both healing vector and, to quote Tristen Harwood, ‘monstrous energy’.[1] Part serpent, the one-eyed King watches over the theatre that unfolds across the industrial spaces of ACCA’s Gallery 1.

Fabian Brown’s Horus is rallied by Jimmy Frank’s freestanding sculpture that features the severed limb of the incredible hulk—salvaged from the roadside—holding a deftly crafted mulga spear. In his essay for Memo Harwood attributes the Brio’s power to an ‘antagonism between the polluted materiality of the present and the devotional renewal of the ancestral return.’[2] In other words, hulk arm versus mulga spear. The weathered materiality of the ACCA carapace—made from Corten Steel—combined with the industrial dimensions of its interior, only enhance this monstrous dance. A paean to industry is performed by the building itself and hence the Brio’s critique of the deleterious impacts of mining on Warumungu Country deliver, with stealth and surprising beauty, a new Trojan Horse.

The exhibition takes over all ACCA’s galleries, spilling out into the foyer and airlock like a metallurgical tide. While some of the work made the 2,700km journey from Tennant Creek to Naarm in a shipping container to be assembled, disassembled and reassembled at ACCA by the artists, a dedicated Melbourne studio, for the months preceding the opening, wrought new commissions. The curatorial process, led by the collective, involved all of the ACCA team with outgoing Artistic Director and Chief Executive Officer Max Delany joining the visits on Country – including to the decommissioned Warrego mine site where much of the exhibition’s material was found. The after-effects of this culturally informed approach will enrich the institution long after Delany departs (one can’t help but envision him departing on a chariot from Mad Max’s Furiosa).

At the entrance of Gallery 1 rises one of the new commissions, bellowing sound and steam punk personality. Recalling the Futurist’s conviction that ‘a racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath—a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace’,[3] this four and a half metre tall Nike, comprised of salvaged mine matter, wears wings of victory made from Shell service station insignia. Titled UAP: Unidentified (Ab)original Phenomenon (2024), here is an act of reverse futurism, or as Harwood proposes, an ancestral return.

Elsewhere in Gallery 1 battered and painted car bonnets are pinned to the wall like oversized butterfly wings in a collector’s cabinet. One is a Ulysses blue. Recalling the painted car doors of desert doyenne Emily Kam Kngwarray, the bonnets also point to the automotive debris dumped on Country whereby local tips are referred to as ‘Repco’. The spirit of salvaging, saving and transforming—a form of trench art (a term reserved for objects made from the waste of warfare by the embattled)—runs through this entire exhibition. Gallery 2 includes geological mining maps inscribed with cultural iconography and with warnings to care for Country. At the western end, Lindsay Nelson Jakamara asserts his cultural authority by working over mining maps with a series of ceremonial marks.

A nostalgic spearmint green covers the walls of Gallery 3 – a nod to the palette of institutional control strewn across the central desert. Presented here are a selection of the early boards and some more recent, including the bold toxic green Masonite squares of Marcus Camphoo Kemarre who exhibits as Double 00. It’s on this type of discarded board that the vanguard statements of the collective first emerged in 2016, from a dialogue between Joseph Williams Jangarayi, Fabian Brown Japaljarri and Melbourne-born Rupert Betheras as part of an art therapy program run through the Anyinginyi Health Aboriginal Corporation.

The temptation to compare the Brio with the early work of Papunya Tula has been irresistible for most, and here in the use of Masonite—a manufactured, colonised wood—a new connection is made. Like the makers of the first wave of works painted on board in Papunya more than half a century ago, the Brio emerges anew from the whole colonial catastrophe with a collective of linguistically diverse (Warumungu, Warlmunpa, Warlpiri, Kaytetye and Alyawarr) cultural men, including Joseph Williams Jungarayi, Clifford Thompson Japaljarri, Jimmy Frank Jupurrula, Lindsay Nelson Jakamarra, Marcus Camphoo Kemarre and Fabian Rankine Jampijinpa. Working with them is artist Rupert Betheras and collaborators Eleanor Jawurlngali Dixon, Lévi McLean, Gary Sullibhaine and Dr Erica Izett as curatorial adviser.

In the final ACCA gallery, the Brio’s signature bricolage is the hero. Darkened walls recall the endless sticky carpeted gaming rooms found all over the nation, across the road at Crown Casino, and the intermittent clamour of failure. These anthropomorphic pokies carry protrusions – found metal body parts that render them as kin to the UAP. Carrying names like 5 Fortunes and Jackpot they also connect specifically to the history of mineral/wealth extraction in Tennant Creek where Jimmy Frank’s grandfather, Frank Juppurula, found gold in 1932, triggering what is described as the last gold rush.[4] At this time Tennant Creek had become a place of refuge for mob impacted by the 1928 Coniston Massacres on Warlpiri/Anmatyerr/Kaytetye lands, south of Warumungu country. Fabian Brown Japaltjari, and no doubt other members of the collective, can trace their family histories to these genocidal events.

Prior to the Coniston Massacres colonists described Aboriginal people in the area as ‘cheeky’ for their attempts to drive colonists away.[5] In a genius strike of return fire, ‘minjinypa’, a Walpiri word that translates as ‘cheeky one’ or ‘troublemaker’, is part of this exhibition’s title. Minjinypa also describes the abiding verve and creativity of this new desert wellspring. As Jimmy Frank Jupurrula summed up at the media preview,

We’ve been massacred

We’ve been put in missions

They took away our land and language

But the resilience is still there and this work represents that.

Footnotes

- ^ Tristen Harwood, "Monsters of Energy", Memo, Issue no. 2, 60-75.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “The Futurist Manifesto”, 1909, Obelisk Art History, accessed 14 October 2024.

- ^ Erica Izett, Shock & Ore: Tennant Creek Brio, exh.cat., (Darwin: Charles Darwin University Art Gallery and Coconut Studios, 2022), 3.

- ^ “Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788-1930”, The University of Newcastle, accessed 14 October 2024.