Margaret Wertheim, the noted science writer, gave a talk about James Carter, a DIY Californian cosmologist, on the first day of the 2002 Biennale of Sydney. Sample Carterism: gravity does not pull an apple to the earth, rather, the earth and everything in the universe is expanding, so the earth jumps up to meet the apple. The collision of respect and reason in Wertheim's head lent her lecture considerable fascination. She was clearly sincere in admiring Carter's unschooled intellect, without allowing his ideas credence. The harder she attempted to work against an insider/outsider dichotomy, the more patronising she seemed.

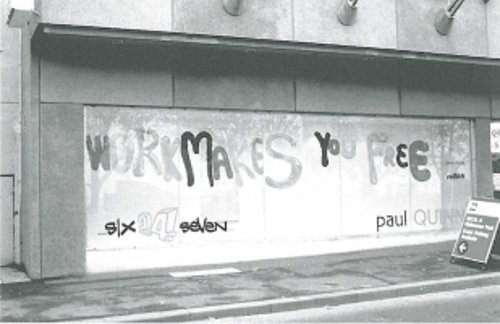

Wertheim's dilemma encapsulates that of the Biennale's Artistic Director, Richard Grayson. The parentheses in the Biennale's title, (The World May Be) Fantastic, form a fox-hole of ambiguity. Grayson's catalogue essay, 'Grasshopper Worlds', (the source of otherwise unattributed quotes below) is ingenious and ingenuous: in the absence of opposition to capitalism after communism's collapse we can dream with Susan Hiller of UFOs, or, disturbingly, join Susan Treister's avatar Rosalind Brodsky in confusing the real with the filmic holocaust. (Aside: naughty Director, including the work of Treister, his partner! But it fits the theme so well&). Shall we do the unthinkable - take a Biennale theme at its word - and ask: how serious is Grayson in proposing his thesis, and is it valid?

We tell stories to describe the world, for survival purposes, and form them to express our wishes, as waking dreams. If Grayson has tripped over a Zeitgeist, as he has happily suggested to the press, surely it is more shaped by escapism than the end of the cold war or a true absence of values. An urgent impulse to bail out explains this exhibition's triumph better than a lack of anti-capitalist rallying points.

Yet at a some level most Australians must be registering the damage being done in this country alone to the poor, Indigenous people and refugee children. The Biennale inadvertently reflects a country and world more self-harmed than happily at play: a comedic counsel of despair, it offers much diversion but if we reflect on Grayson's words we wind up laughing on the wrong side of our faces. The collapse of a bi-polar world 'in which all alternatives to Marxism are equally meaningless' does not justify idiocy. Those terror attacks did not so much change the world as reveal its reality to the West, like a flash gun popped in a slum alley: a place of roiling tensions born of tearing inequalities, propped up by expanding military budgets and reactionary policies. The world, sadly, is still rather serious.

But politics here, as usual, comprise untrue parallels to art. A deeper nub of Grayson's essay - the point which comes closest to matching words to art - occurs in his invocation of that state of radical otherness which occasionally comes over people, for example a child wondering 'what would have happened had its parents never met &This, as every child knows, is tremendously scary and tremendously exciting.' Such inklings of the ultimate, unknowable contingency of the universe challenges the boundaries of one's subjectivity, intimating the unknowable beyond.

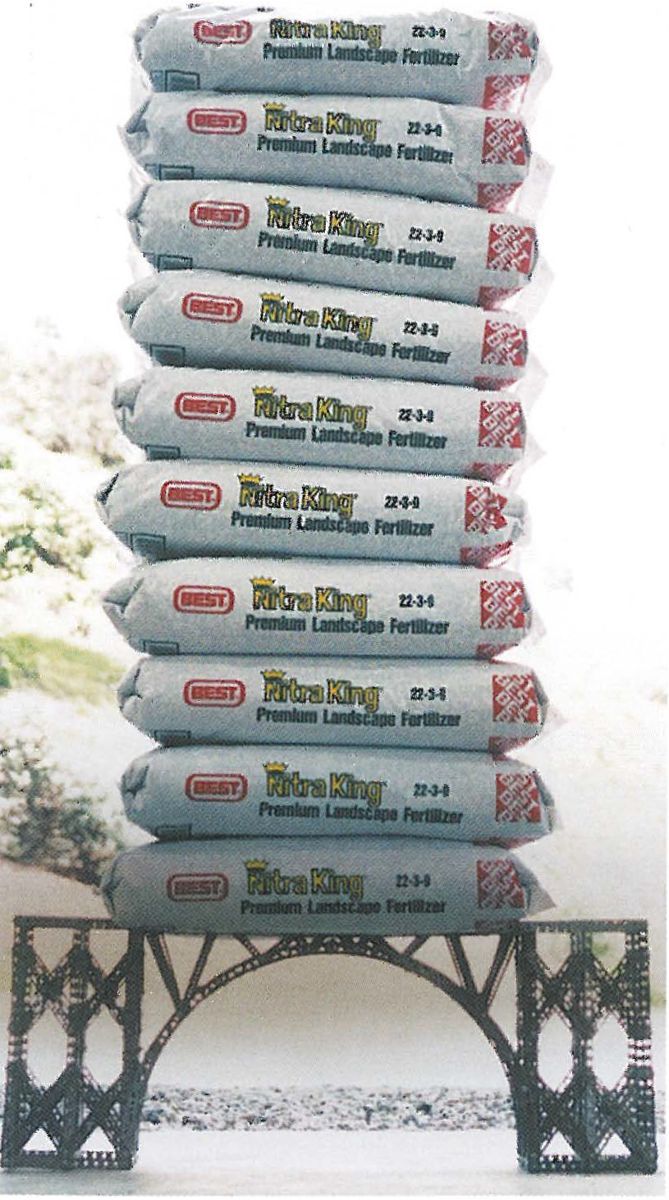

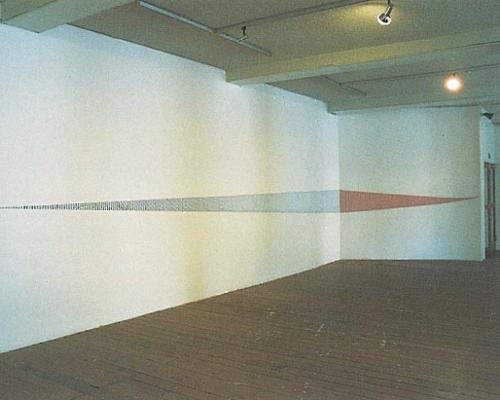

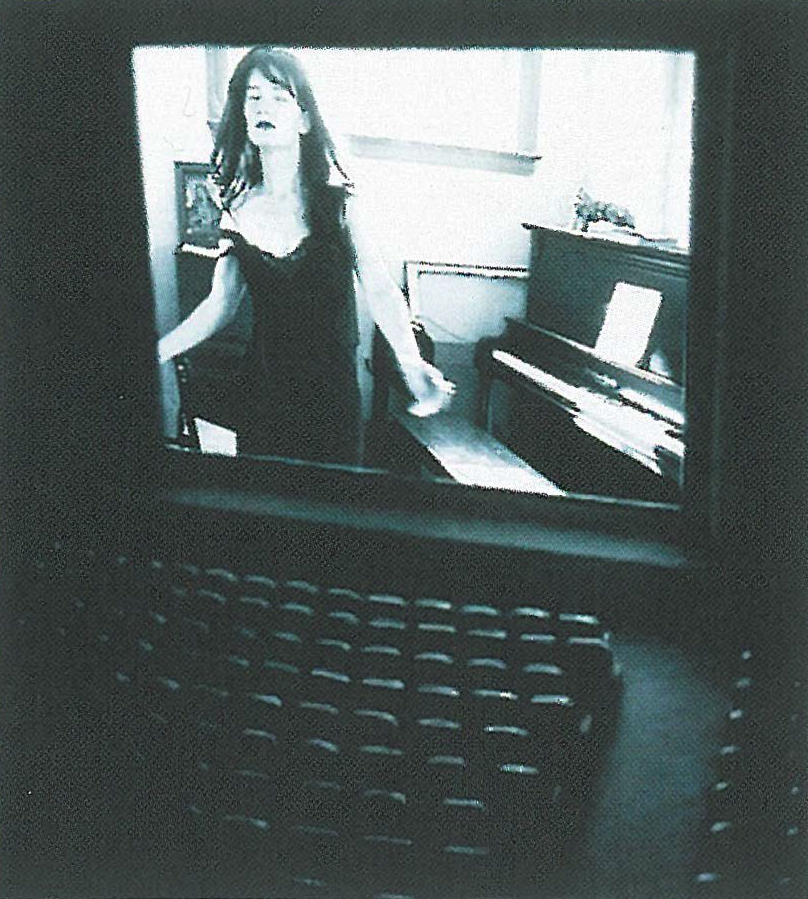

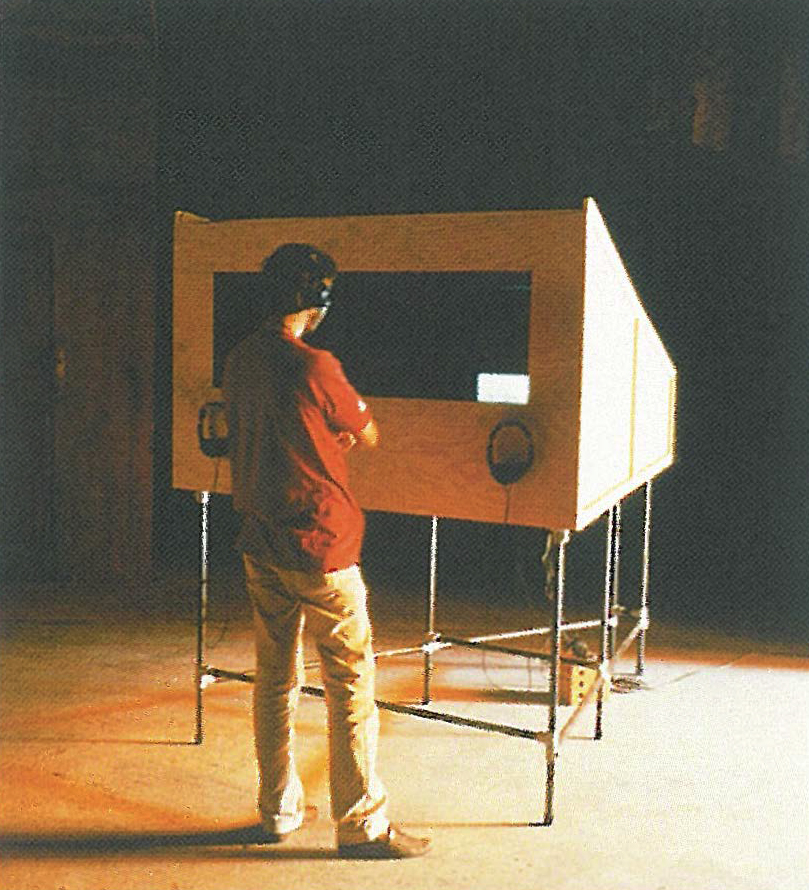

Does Fantastic conjure up this condition? There is genuine strangeness in the gender-confused fixations of Henry Darger, who died in 1972: his work is an anomaly in an exhibition otherwise devoted to living artists, all of whom he exceeds in oddity, and who range widely in the fantastic stakes. Something of Darger's isolated, obsessive, made in a shed/ basement/bedroom quality is to be found in the armature of Chris Burden's Indo-China Bridge, which speaks of impotent mastery and personalised imperial guilt. A comparably dinky, delicious quality is viewable in the miniature cinema of Janet Cardiff: it evokes the delight model-making can induce in the eternal child. Veli Gran might shake hands with Darger in imparting private worlds, though as a distanced narrator rather than subject. Eija-Liisa Ahtila's Lahja/The Present comprises TV spots and short films offering self-forgiveness even from the hard place of (represented) psychosis. Katarzyna Jzefowicz's carpet of cut-out celebrities is in the zone of the wonderfully aesthetic rather than fantastic, until one factors in the sheer slavery of its labour of its production. If Miwa Yanagi's brilliantly staged photo/text evocations of ideal grandmotherhood excel, they are too knowingly clever, like most of the works in this show, to convey existential uncanniness. In perhaps the most profound work of all, pun intended - an outstanding work in a strong field of video pieces - the underwater cyclos of Jun Nguyen-Hatushiba function more as a metaphor than a sea-change for events in this world.

But art is bigger, dumber, better than words. Grayson's essay and press statements are so disarmingly provisional, witty and charming that the crude analysis above may seem misplaced, a spectre at the feast. Further, the fact that Grayson's dance has Sydney mesmerised might have something to do the character of the Biennales since the mid-1990s. Lynne Cook's, of 1996, elegantly trailed the coat-tails of the 1980s theory. It also presented the greatest quotient of memorable art (Ann Hamilton, Yinka Shonibare, Philip Taffe), even if its title, Jurassic Technologies Revenant, was too literate for the art world's tabloid brow. The politics around that Biennale were poisonous, the air having grown foul since the previous one in 1992/93. Jonathan Watkins's flirtation with the quotidian, Everyday, 1998, was a diverting, hit and miss affair which partly prefigured the entertainment level of the current event. Nick Waterlow's golden hit parade in 2000 offered an oasis to the labile empire of Sydney Biennaledom. Grayson, in contradistinction to all these exercises, neither proclaims high seriousness nor asserts a blurring of art and life, so much as an alternative lives and realities.

If this show contains a mix of genuine, strategic and zero outsiderhood, it richly vindicates the employment of a Director himself somewhat beyond the established curatorial pale. Fantastic's weirdest reaches, incidentally, are matched at the Museum of Jurassic Technology, Los Angeles, an institution devoted to unnatural history. Its motto: to guide the learner 'along, as it were, a chain of flowers, into the mysteries of life.' The museum was created by an artist, David Wilson, just like the Biennale in question. A trend to applaud.