Photography has been part of the collections of our galleries and museums for so long that it takes a substantial effort to imagination ourselves in an age when such recognition was far from universal. A retrospective of the work of Bill Brandt at the Monash Gallery of Art serves to remind us just how recent are some of the works that give photography its present status.

The bulk of Brandt's published work was photo-journalism or reportage- more or less, as standards for captioning and titling in the days when Brandt worked for Picture Post and Weekly Illustrated were somewhat lax, to say the least. The show at the MGA covers a range of this work, and it's worth a look, even if it were only for the historical value. Brandt himself noted later in life that English society had altered so much in the period after the second world war that the era between the wars seemed to belong almost to another century. Besides, Brandt is never less than a fine craftsman, and his shots of all strata of society busy at work and play rival Barassi or Evans.

This is not, however, the work that makes the show worth the trouble to see. The things that are, are Brandt's nudes and landscapes. Quite a bit has been made of Brandt's brief (three month) stint in Man Ray's studio in Paris in the late twenties. And you can see the influence there, sort of. But Brandt had remarkably little use for Ray's techniques of shadowgrams and solarization. Instead, what we see is the slow absorption of the processes and aesthetics of surrealism, to the point where Brandt achieves a kind of symbolic double-take in his photographs of the nude in the fifties. It is this work that pushes the boundaries of how we see the human body, and how we can place it in context to nature, and it was developed slowly.

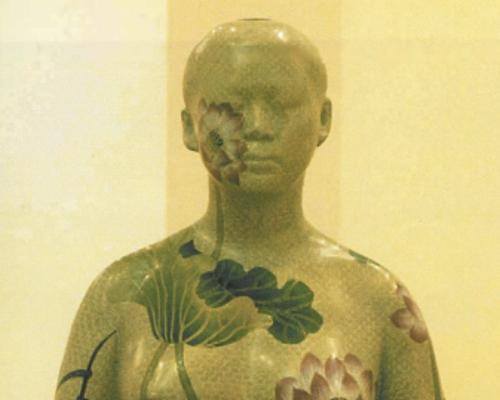

There are sufficient key works in this show to show how carefully Brandt felt his way toward this new vision. What he ends up with are fragments of the body -perhaps the feet, or interlaced fingers, or an elbow crooked over a breast, distorted with wide angle lens, bleached out on high-contrast paper, and often fiercely cropped. In works such as Nude, Baie des Anges and Nude, East Sussex Coast, dating from 1959 and 1960, the results are often difficult to recognize as the human form at all: they have the appearance of boulders precariously balanced, or that of fungi or sponges cast onto stony beaches - but rocks that give off an erotic charge, that might be crevices, folds, swellings of the body... and so they are.

These images are now half a century old, and Brandt's aesthetic has been strip-mined by a legion of lesser talents, so we are in danger of retrospective cliché - after all that plagiarism, it could look pretty cheesy. The surprise is that it's not. The other works in the show to stand out are the cityscapes and landscapes. The most impressive belong to three bodies of work: a series taken during the depression in the north of England, London during the blitz, and images of the countryside taken in the immediate post-war years. Brandt's images of a blacked-out London, lit by a moon strong enough to make unlit streetlamps cast shadows, border on dreamscapes, as does a shot of Stonehenge in the snow.

Brandt achieved considerable fame as a portraitist and it is these works that take the show to Canberra. For the greater part these are solid, workmanlike efforts but a few, such as the images of Henry Moore gazing at the lens over his work and a solitary Francis Bacon on Primrose Hill capture their subjects with real force. There is a remarkable series of ultra-cropped images of artists, all old men, each represented by a single weathered eye. The effect is that of staring at an elephant at a range much too close for comfort, but each retains something of the character of the sitter. They seem to sum up Brandt's view of his own career: an intelligent lens on life.