What can one expect from an exhibition of recently graduated students? New talent, new trends, a comparison of different teaching strategies? And against which criteria should such a show be assessed? Is it a launching pad for the young and hopeful, a showcase for art academia? These questions inevitably present themselves when one wanders through the smorgasbord of techniques and approaches that constitute the exhibition.

Despite the catchy title and its youthful image (even though the participants are representative of a wide demographic spectrum), there is something faintly bureaucratic about a show aimed at providing institutions with a routine opportunity to strut their stuff. This is the kind of exhibition that in other, more centralised and heavily governed countries – say France or Germany – would probably be run under the aegis of some government department.

Here in Australia, however, we enjoy small government and arm's length funding, conditions which should secure a measure of independence to the art world. It is therefore not surprising that a contemporary art space like PICA has been running this annual project for the past eleven years. So that what could easily have become a dreary mini art fair for the tertiary sector is in fact a reasonably festive occasion, warmly welcomed by local emerging artists. Bec Dean, PICA's newly appointed exhibition co-ordinator, should be credited for pulling off what must have been a very demanding organisational feat, especially considering the financial penury that contemporary art spaces and university departments have to endure in this country (small government goes hand in hand with small government funding, a situation that guarantees relative independence and absolutely poverty to our art institutions).

Perhaps the right criterion to assess Hatched is one that measures what art schools have been able to achieve despite the unconscionable funding cuts successive governments have inflicted on them. Approached from this angle, the results are mixed but not discouraging. Walking through the rather overcrowded rooms of the exhibition space one senses a degree of energy. On closer inspection, however, this first impression is partially corrected, as many a work, and some of the most successful ones at that, cast a reflective, almost introspective, eye on the more elusive aspects of everyday experiences, for example, David Lawrey's photographs of cardboard and plastic models of imaginary interior spaces. These illusory environments are both ordinary and mysteriously evocative, effects which are mainly due to a lyrical, almost other-worldly play of light and shadow that imbue their seductive emptiness.

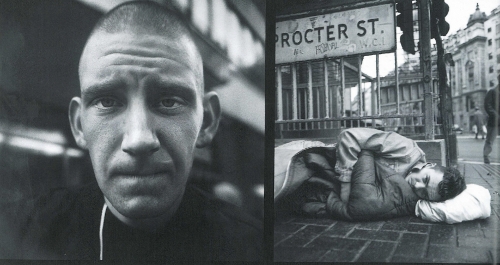

A different kind of everyday is at stake in Joachim Froese's large black and white photographs, a series of greatly magnified images of bees on a ground covered in ordinary detritus (apple peels, scraps, lumps of dirt). These bees are intriguing fellows, engaged as they are in some unfathomable yet somewhat sinister ritualistic pursuit. They resemble a cross between Samuel Beckett's characters and alien creatures from a sci-fi movie – silent actors in a cryptic scene which is both sombre and monumental. Quotidian images are also the focus of Ros June's sensitive reworking of family snapshots. The photographs are cut up and rearranged in a process that echoes the cognitive processes through which we reprocess our memories to discover, or create, new meaning for the past. The reworking of the everyday is also apparent in Brendan Van Hek's hinge: a joint that functions in only one place. The artist has 'deconstructed' a door, dismantling, photographing and rearranging it in order to reinvent its material and conceptual features (an idea that must owe something to Duchamp's Door, 11, Rue Larrey.)

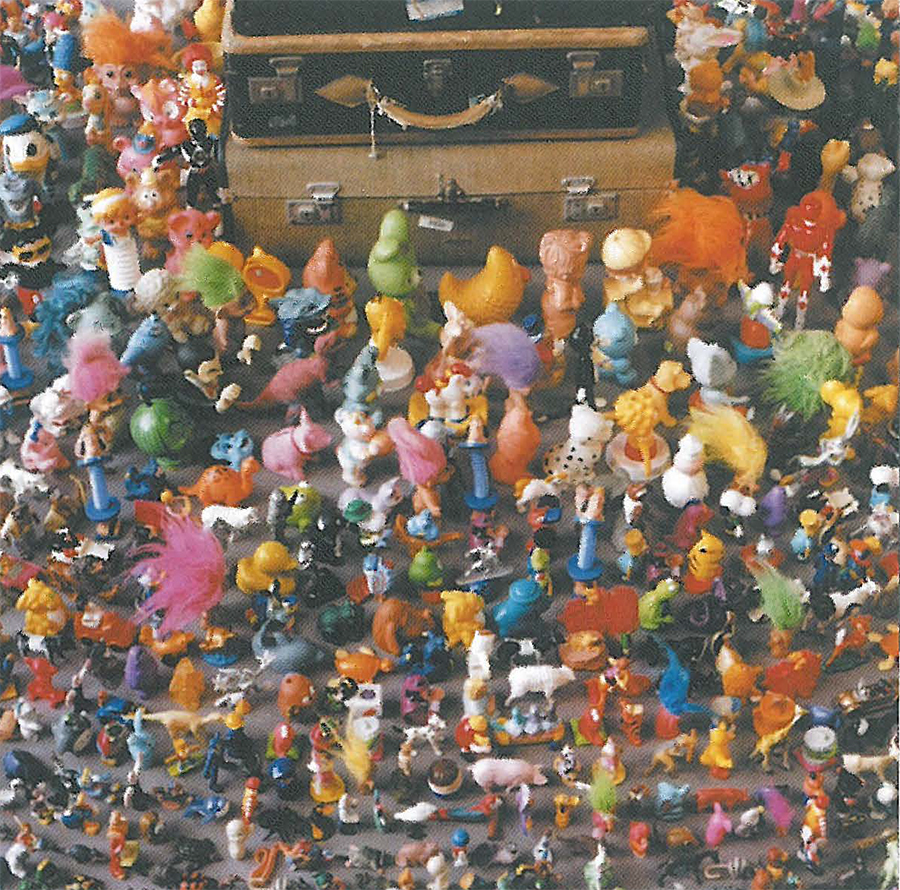

Of course not all the works in the show evidence the same level of sophistication or theoretical ambition. As is to be expected deja vu abounds in an exhibition in which most artists are still striving to find their distinctive voices, but some succeed despite a certain degree of naivety. This is the case with Shaun McGowan whose Travelling to Mega is a kind of ziggurat made of old suitcases surrounded by a circular procession of toy characters. The work is both solemn and playful providing a touchingly poetical commentary on Australia's response to the refugee 'crisis'. Many other artists in the show have made references to topical political and social issues, but too often the content of the work has not been translated into an appropriate artistic form.

Finally one must comment on the display, which looks a bit crammed, especially on the first floor. The exhibition fills every nook and cranny of the building and, in fairness to the very dedicated and capable PICA staff, considering the diversity of mediums and formats involved must have been a nightmare to hang. But perhaps size is just one of the many aspects of this exhibition that need to be reviewed and revised.