A modern romance has grown up around the figure of the reporter, especially the foreign correspondent and the crusading political journalist. The journo is a freebooter who travels lighter than the rest of us, yet retains a magisterial conscience. His clear insight gets straight to the essentials of a situation and the worth of a person without prevarication. He goes to places that we ourselves are too frightened to go to and involves himself in problems that we are too complacent to face. The journo's role takes on a religious dimension in modern society when he redeems us from our homebound, consumerist, overdeveloped first world hypocrisy. Australia is certainly not immune from succumbing to this myth, witness the fictions of The Year of Living Dangerously and the second cast of Sea Change, however the messiah of this cult would surely be the British Bruce Chatwin, although Paul Theroux is a good transatlantic mimic and Bill Bryson presents a parodic take on the genre. Britishness was essential to Chatwin's performance.

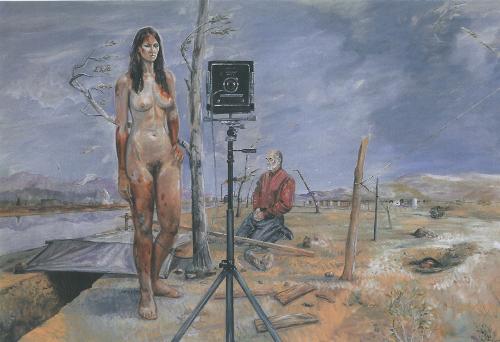

Michael Wood did it for television, exactly replicating Chatwin's twin British universes of art history and adventuring. Chatwin took the perennial myth of the good white man and updated it by adding a genuine sense of aesthetic insight and a new multi-culturalism. Whiteness was not to be measured by skin but by the intensity and purity of one's personal and cultural performance. The updated Boy's Own adventure involves searching exotic cultures and places not to kill the natives or plant the British flag, but to locate a colour and poetry missing in whitebread society. Afterwards one wrote The Book. Older Boys Own heroes such as T.E. Lawrence had already identified that "noble" examples of the Other were in fact the true soulmates of the British in a modern world where masculinity was bound in and debilitated. This continuity identifies the traditional basis of the modern cult of the foreign correspondent. Just as Virgil guided Dante around Hell, there are any number of white men with both conscience and real world authority, cultural and political, waiting for us at the gates of the Post Colonial adventure. John Pilger for example remains as Gilbert and Sullivan memorably said "an Englishman".

How strange, considering the strong Anglocentric basis of Chatwin's aesthetic, that its best aspects could be replicated flawlessly by an Australian writer also schooled in something of a Galliopolli-esque persona, no-nonsense, practical masculinity. I mean no insult in placing The Carpet Wars by Christopher Kremmer within Chatwin's genre. Kremmer's decade long textual journey through the Middle East, Islam and its conflicts is informed by the best aspects of this modern genre, leaving aside the problematics of undying heroic white males for the moment. Evocative turns of phrases make visible far away places for the couch-bound reader. Anecdotes flow freely, well paced in classical writing style, until the denouement, either humorous or tragic. People whom the reader will never meet take on real dimensions through the text. The references and bibliography act as a portal for further informed reading about ancient and modern history, culture, religion, ethnography. The Carpet Wars is no beachside or banana lounge mental masturbation. I generally find current fiction ultimately unsatisfactory, conversely the non-fictional Carpet Wars has a serious mission. Accessible and moving, poetic and engrossing, it speaks of cultures and events usually rendered fixed and one-dimensional by western media.

Current political events make reading The Carpet Wars an "ought" rather than a "should". In tracing Australian visions of Bush's "War Against Terrorism", The Carpet Wars is a moving, highly significant contribution to the debate. Wherever you stand, reading it is productive and provocative. This is not the story as told on Good Morning America and gains in value especially when the scripts and stereotypes have hardened so rapidly. I am no expert, but Kremmer's meandering pattern makes plausible the multiple interaction of national history, colonial expansion, social dislocation, capitalism, religion, prejudice, ignorance, ambition, both individual and collective, that has shaped modern Afghanistan and the web of nations drawn into the modern 'crusades'. The misery of those on ground zero is effectively drawn, especially the sense of hopelessness when the war of liberation against the Russians rapidly transformed into a local civil war. In these circumstances the Taliban would become a viable alternative as the last men left standing amid the nihilistic desperation of a people for whom the frontline has been a lifestyle (not of choice) as long as they can remember. Their reality and the decisions they make under such pressures are thankfully not yet ours, but Kremmer also indicates how the West is clearly implicated. Russia and the United States are not adversarial players in a stake for truth, but alike shadowy, opportunistic interventionists on the sideline, moving to assist when it suits them, and at other times leaving the Afghanistan nation and the peoples oppressed by Islamic tyrants to their own devices, picking up and taking down allies seemingly at conscienceless whim to those in the firing line.

As in a folk tale retribution will surely follow and the chickens will come home firmly to roost and one reaps from the whirlwind that one sows. The West has provided tuition and goals for those warlords and local politicians, who have grafted consumer goods, effective weaponry and an expanded sense of scale and possibility onto traditional patterns of corruption. There is a real sense of karma and payback in the 1998 United States flying cruise missile attack on a Bin Ladin funded training camp, that renders some of the Australian reactions to September 11th from the "I told you so" letters to the editor and the "refugees welcome here" signs appearing on office doors in multistoried office buildings (as if they could even get past the receptionist ... "Where did you say you come from again? Just wait here and I'll get someone to see you") as the facile, easy, knee jerk gestures that they were in reality.

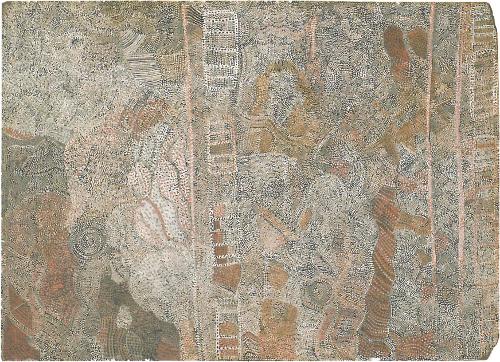

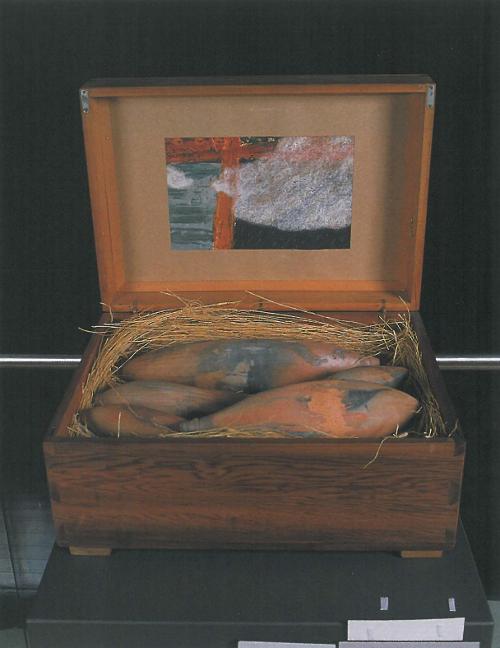

The Carpet Wars is an art book, in so far that it also tells the story of carpet as an artform, its production, dealing and collecting, as a conscious alternative to stereotypes of Middle Eastern and Islamic culture as militant, aggressive and inhumane. The decline of a traditional skill that enthralled other cultures across the world, the rapid development of a western driven trade as decorator showpieces, complete with endentured child labour and fake aging techniques that ironically shorten the lives of expensive rugs becomes for Kremmer an effective metaphor of the destruction of the integrity of the fabric of Afghanistan society. Wherever Kremmer travels, seeking and buying carpets provides a means of bypassing an adversarial vision of evil Islamic nations. Through carpets he brings the war home underfoot in Australia, reminding us that those evening news dervishes in keffiyas, dancing with machine guns are of the same culture that made the carpets so admired for centuries in the West giving a sense of the interconnectedness of things and people, that wartime propaganda seeks to negate. Kremmer frequently deprecates his own lack of eloquence in comparison to Persian poetics and rhetorics and the languid generous formats of traditional hospitality, but the gentle carpet narrative is worthy of his desire to awake readers to unfamiliar cultural patterns and rhythms, by presenting a story in a different manner than the dialectics of fact and argument. Explicating alternative cultural habits and values awakens the reader to the normality and reasonableness of the people whom Kremmer meets in seeking out carpets, human faces in the battle zones.

The Carpet Wars does not entirely escape the shadow of Chatwin. The nobility of those Others now accepted as brothers was increased by their sharing with Chatwin an unease around female culture. This book is, like many of the nations it visits, strongly divided by gender. Women generally hover at the sidelines, although the protection of their honour and that of the family is a constant and potent motivation to masculine defensive actions throughout the narrative. For practical purposes the values of both culture and religion are accepted in the narrative, although Kremmer unpicks the religious complexities of the fraternal elements of intra-Muslim and ethnic conflicts. He notes how women who were university students one day were banned from classes the next and wherever he goes in Afghanistan the pavements are filled with begging war widows, whom the Taliban banned from working to support themselves. For Kremmer feminism is yet another brand of ill-informed, spasmodic Western intervention that causes as many problems as it solves.

The veil as female protection is seen as an answer to generations and centuries of opportunistic social lawlessness. Yet whenever I think of the Taliban I also think of the Handmaid's Tale. Kremmer likewise indicates that the true, universal enemy is fundamentalism. To understand the Taliban he advises we must imagine a world where the rigid, ill-informed values of an American tele-evangelist becomes law. Much of the regional social and political volatility is caused by men schooled only in repeating Koranic verses trying to run a modern nation state with its associated infrastructure and a once advanced economy. How can individuals defend themselves against sectarian fervour and the inflexible, unforgiving beliefs of the ignorant, if not by optimism and the milk of human kindness?

On Australian pay television World War Two reigns, especially if a war veteran keeps hold of the controls. After seeing the war replayed in every possible permutation almost nightly, the idea occurs that war is itself dependent upon a deadly version of genre fiction's use of fixed, predictable stereotypes, comforting also to fundamentalists. Pentatonic soundtrack music means that the Japanese are coming and we can be certain that some will wear glasses and some will be smart and sarcastic and others cruel, unthinking dogs, just as Germans will be either fat or thin and, if officers, may do decadent things out of hours if the director has budget and imagination. Of course they will all lose after a reasonably entertaining interval of treachery and tension. World War Two, like an Agatha Christie novel, indicates that the wrongdoer will be located and punished.

The Carpet Wars – as a true war of the post modern era offers no such comfort, just a cycle of incidents punctured by the baroque light and shade of action and violence, the galgenhumor of the grotesque or regret for friends lost violently and needlessly. I personally begin to doubt even the rightness of those old stories of World War Two as being no less substantial than the folk heroes woven on the new war carpets. Against this meaninglessness, the human spirit just perseveres for want of any alternatives, sets down a glass of warm green tea, seeks out the treasure cannily buried by centuries of accepted practice at the very bottom of the pile of carpets and discusses the merits of its design and handwork.