Gordon Bennett: Illuminations or a season in hell

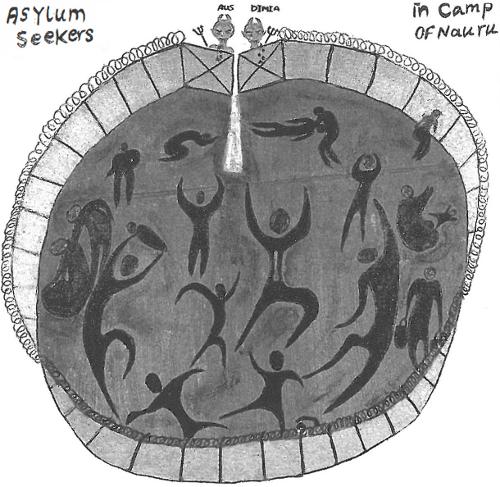

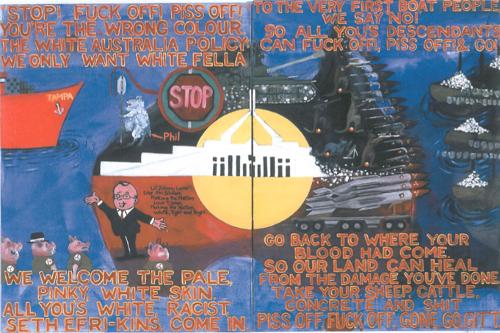

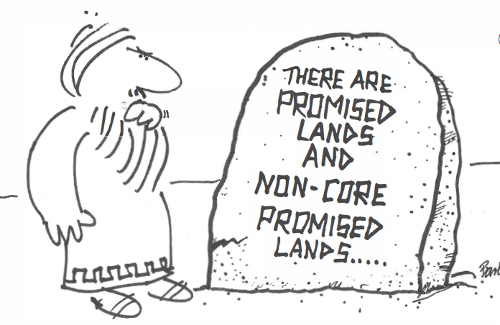

Responding to 9/11

The Carpet Wars by Christopher Kremmer by Harper Collins Sydney 2002