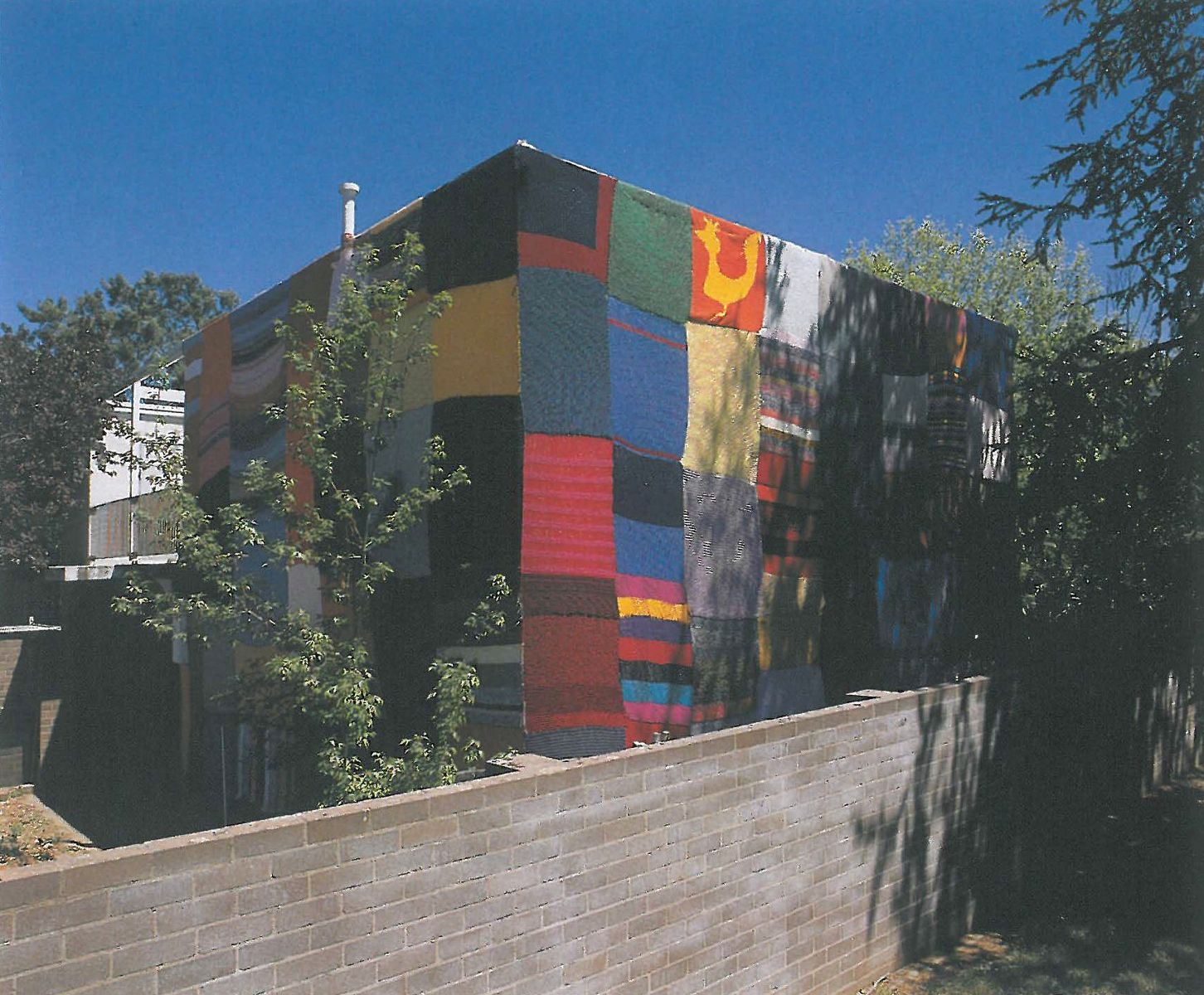

For a brief three-week period a two-storey modernist maisonette, which backs on to Canberra's main arterial road, was transformed by a knitted cover. Occupant/artist Bronwen Sandland is known for her knitted objects. For the past ten years she has conjured knitted personal column advertisements, covers for long-forgotten objects that have inhabited deserted shopfronts, and strangely evocative forms for installations in sex shops and other non-traditional spaces. For housecosy she needed help, and over 100 volunteers responded to her call. Armed with 10mm needles and wool in many colours, we knitted. Yes, I was one of them, and I can tell you that wielding such large needles was a strenuous activity. The resulting 1-metre squares varied unaccountably in size and flexibility, the tension inconsistent from one knitter to the next. Rather than being an obstacle the variety only added to the final result - this was emphatically not an industrially produced fabric (tarpaulin, drop sheet or sail) but the product of individual labour.

The distinction set up a crucial counterpoint to the spare, purist lines of the house, designed in keeping with utopian Bauhaus principles by architect Sydney Ancher, whose 1959 complex is listed by the RAIA as 'significant'. The perfect white box (an inverted white cube, as one commentator noted) took on the appearance (and smell) of an Op Shop, that repository of discarded, unfashionable objects, ersatz museum of failed modernist trends. If it had not been so well done it would have remained an ambitious, shambolic gesture. But the final covering was impeccably realised, mimicking the sharp lines with the precision of fit, mocking them in the joyous DIY jumble of colours. This was an intelligent commentary on the tension in the Bauhaus ethos itself between the hand-crafted and the industrially produced, a tension which remains largely unresolved. Hand-made, when not done by an unpaid, usually female, workforce – in the spirit of 'knit for peace' campaigns – is prohibitively expensive: an obstacle neither William Morris et al, the Omega Workshop, the Wiener Werkstätte nor the Bauhaus could overcome. It paradoxically inhabits the worlds of the poor and the rich, product of both necessity and luxury.

Knitting, like other time-consuming crafts, is often driven by an urge to protect, to personalise and to give: the jumper for one's family, the ritual tea cosy, the booties for a neighbour's baby. For those with only time to give, the value is in the making (perhaps this is what gives the Op Shop its particular air of sadness?). Thus, a certain brave melancholy imbued housecosy. This is a most unloved neighbourhood. The public housing project is now less than utopian, plagued by petty crime, victim of random acts of arson, traffic noise and unemployment. The artist has claimed 'I do not always feel safe here'. For the duration, housecosy became a vehicle for communication; neighbours were consulted and included, passers-by stopped to chat, commuters enjoyed this quirky visual treat, and visitors could satisfy their curiosity about one of Canberra's minor landmarks.

I am not one who believes that public art can solve the ills of bad civic design. If one could ever hope that public art projects contribute to our urban environment, then housecosy is a success story. It encouraged us to pay attention to the regions of our city forgotten between new developments and heritage precincts, and to reflect on the socio-political forces that have made knitting an exotic occupation. housecosy made visible the relationship between personal action and public space.

The enormity of the task gave housecosy a certain David and Goliath quality. The incongruity of the fabrication set it in the realm of parable. Its rupture to the suburban landscape made it the stuff of dreams. For a brief three weeks Lyneham was a satellite town of Lilliput.