Australian Print Symposiums are held irregularly, the first was in 1989, the second in 1992, the third in 1997, the fourth in 2001.

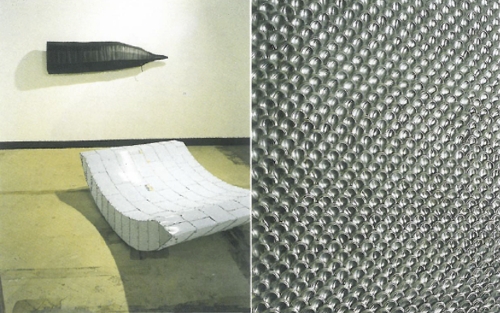

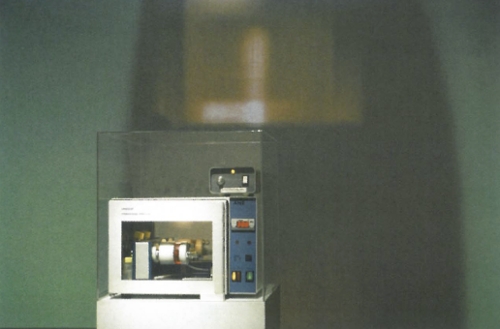

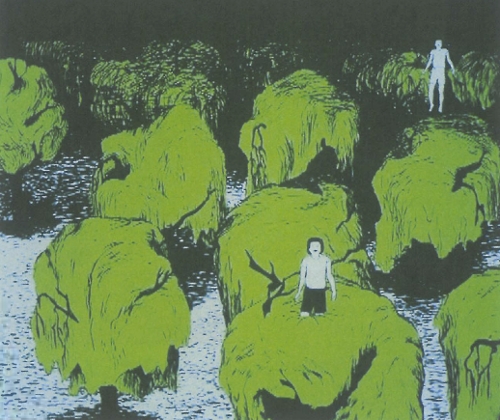

The Fifth Australian Print Symposium was accompanied by a series of exhibitions throughout Canberra which celebrated printmaking in all its forms from place original face down to copy at the Canberra School of Art, an exhibition revolving around the use of photocopy technology, that included something curiously wonderful – Nick Strank's B.A.T. - a photocopier cast in bronze, to Robin White's tapa-inspired relief prints bringing together Pakeha and Maori imagery at Helen Maxwell Gallery.

Megalo Access Arts, in extensive new premises, showed an exhibition of six artists, Penny Cain, Christine James, Garry Jolley, Suzanne Knight, Erica Seccombe and David Sequeira who had undertaken residencies there in 2002, while the now defunct print workshop Studio One (1983-2000) was represented by a historical survey show of prints acquired by the Canberra Museum and Art Gallery and shown there alongside Breaking the Ice a major exhibition by Jörg Schmeisser of etchings, paintings and drawing of Antarctica.

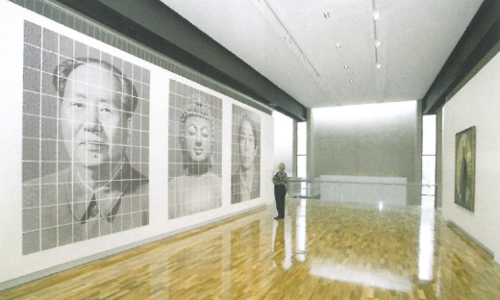

The ability of the print to be in several places at once, and thus to be collected in large quantities by institutions which are thus able to show complete slices of art history was also visible at the National Gallery of Australia where a selection from over 3000 prints acquired in 2002 from the Australian Print Workshop were on show.

Printmaking has the reputation of being an art practice overly concerned with technique. The question of how it was done can dominate over what is done. Also the more traditional and exacting techniques are sometimes considered archaic as the labour involved can today so easily be digitally imitated or bypassed.

Yet the turnout at the Symposium, full house for most sessions, suggests there is life in printmaking.

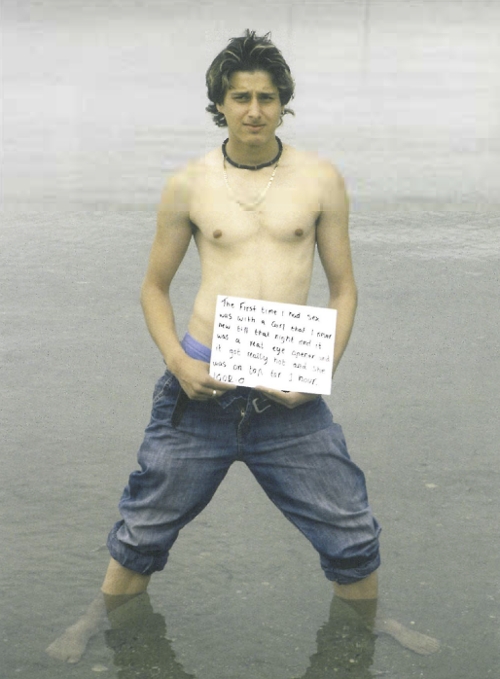

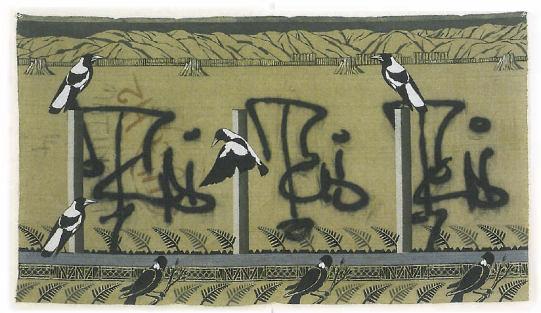

The traditional areas of printmaking are as full as the experimental edges of the field such as stencilling on the street. Stencilling on the street, a form of graffiti, is of course not new but dates back at least to Pompeii yet it is made or becomes new each time it is embraced by a new and young set of people who utilise its spontaneity and graphic strength to make political statements. Stencil artist James Dodd cut a stencil about John Howard while on a panel to show how quickly it could be done while Din Heagney showed images of agitprop stencil activity in Melbourne.

The creation of a multiple is the most consistent recurring feature of a print and it is this feature which enables prints to be easily circulated. Somehow a dignity and special quality inheres in the process which creates a print matrix, however crudely or finely it is done. A quality which you can be sure is as old as art. The engraved line, whether onto stone or sand, bone or shell, skin or wood, is contemporaneous with both hand stencils and ancient rock art whether in Europe, Africa, Asia or Australia.

Two current buzz areas in art – collaboration and the regional statement are well represented in printmaking in collaborations between Indigenous artists and printmakers. For the last twenty years the feel for materials and the graphic brilliance of Indigenous artists has found outstanding expression in printmaking and Basil Hall, once of Studio One, then Northern Editions and now Basil Hall Editions in Darwin, is an exemplar of managing and executing such collaborations. Speaker at the Symposium Alison Alder, a Megalo ancestor, who co-coordinated the Puntuu portrait project for the Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre in Tennant Creek, is another example.

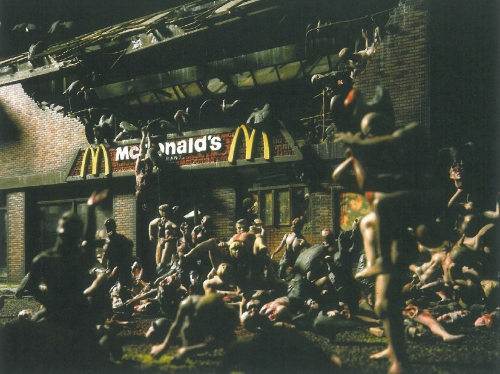

Printmaking in the wider region, i.e. Asia Pacific was also part of the Symposium brief and Chaitanya Sambrani spoke about the importance of a poster project in Pakistan and India (see www.members.tripod.com/aarpaar2) in which unauthorized statements dealing with the violence that underpins rampant consumerism could be made and remain under the radar of both the state and the art market. Sambrani emphasised that in the Third World art is on the frontline and printmaking, whether digital or handcut, is hard in there.