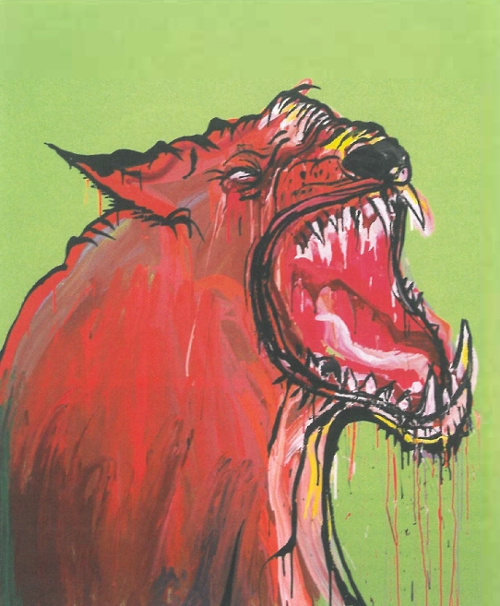

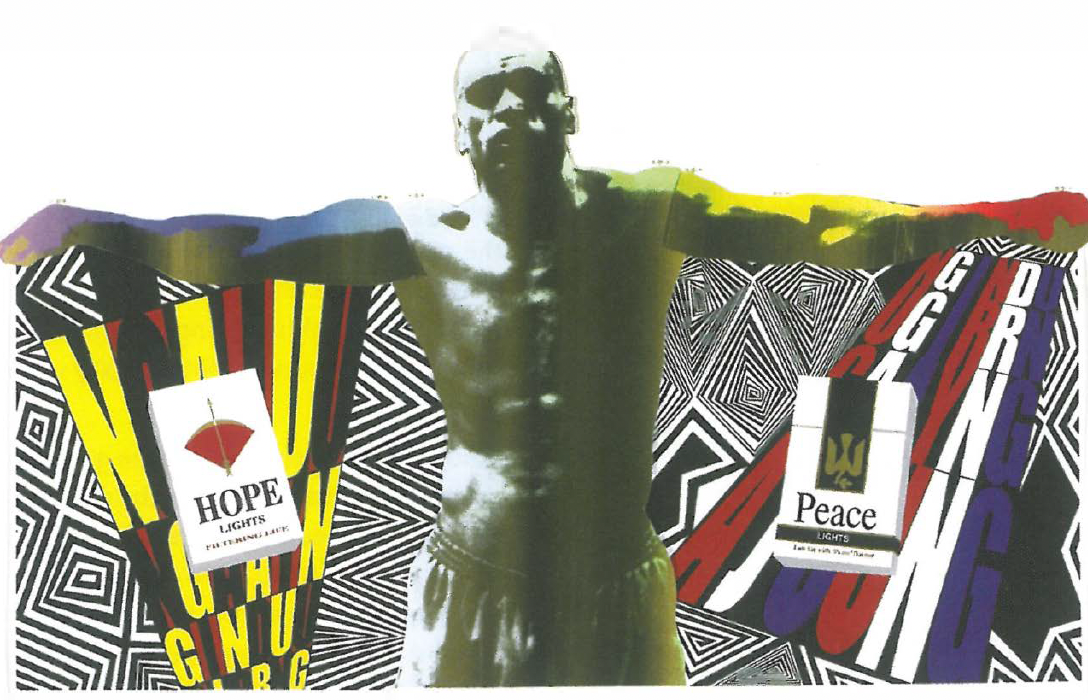

Brook Andrew has always been uncomfortable about being labelled an 'Aboriginal artist'. His latest work, nevertheless, centres on the politics of Aboriginal Australia within an international context. The pivotal work in Hope & Peace is a collage/screenprint of Indigenous footballer-turned-boxer Anthony Mundine, arms raised, Christ-like. Under each arm, cigarette boxes with the twin messages 'hope' and 'peace' float on towers of block capital letters, with psychedelic patterns of black and white behind. The colours are almost neon in their flat loudness – the rainbow of Mundine's arms, the billboard-style lettering and the inclusion of that emblem of commercialism, cigarettes – scream a pop-art aesthetic.

At first, the meaning of Peace, the Man and Hope is not clear. Other works show similar colours and themes – chewing gum packets, tins of rubbing tobacco, words shot from twin guns, all on a background of angular, geometric designs where black and white or black and brown lines form sharp points in a repeating pattern. The words themselves are in big, advertising capitals, with false perspective showing them towering upwards or shooting diagonally across the work.

What becomes increasingly clear as you explore the work is the reference to war. Cigarettes, rubbing tobacco and chewing gum are all cliches that form part of the iconography of the American soldier as seen on film and television. Words start to make themselves clear; 'hope' and 'peace' are joined by war-related terms like 'friendly fire' and 'against all odds'. Then, obviously, there is the imagery of guns themselves. Delving into the catalogue essay, it becomes clear that war is indeed the theme, and in particular, the current war in Iraq and the war on terror.

The rainbow colours of Anthony Mundine in Peace, the Man and Hope reflect the rainbow-coloured flags that Europeans flew outside their windows to show that they advocated peace in the lead-up to the war in Iraq. Andrew used the brand names of cigarettes (Frontier Lights, Peace, and Hope) and of chewing gum (BlackBlack – high technical excellent flavour) taken from real brand names in Japan. He is highlighting the irony of using the terms 'peace' and 'hope' to sell the ultimate in American consumer goods, cigarettes and chewing gum, to the post-Hiroshima Japanese.

References are also made to Andrew's Wiradjuri heritage, including the patterns in the background, which are derived from traditional Wiradjuri designs. Some of the words, too, are Wiradjuri – 'Ngajuu ngaay Nginduugirr' means 'I see you' and 'Nginduugirr ngaay ngajuu' means 'You see me'.

But the main symbol in Hope and Peace is Anthony Mundine himself. Obviously there is a tie-in to the pop-art influences that are so striking in this work – screenprints of celebrities are an important part of the pop-art aesthetic. Mundine is also a hero for Indigenous men, including Andrew, who hopes to give Mundine one of the prints to hang in his gym. According to the catalogue: 'It is impossible to ignore the masculinity of the images. Anthony Mundine is a consummate athlete. He is also a Muslim, and the rigours of his religious conviction, such as total refrain [sic] from alcohol and other harmful substances, are qualities that are just some of the parts that go to make this man a hero among Aboriginal people' (Marcia Langton, catalogue essay, Hope & Peace).

We all need our heroes and Andrew gives us one – a hero to stand alongside screen icons from the 1960s – Marilyn, Elvis, Jackie O. And in presenting a hero who is an Aboriginal man, strong, powerful and principled, Andrew is contributing to the task of recognising those Indigenous men and women who serve as role models, not only to the Indigenous population, but to the rest of Australia as well. Mundine, whose image as a black man (and even his conversion to Islam?) has been influenced by African American culture, and by Andrew, who cites influences for this work from Japan, Barcelona, and Germany and Poland, from the wars in the Middle East, as well as reflecting Australian concerns, give this work a national and international significance.

In the catalogue essay, Marcia Langton relates the story of Wiradjuri hero Windradyne, who fought a fierce resistance to Governor Macquarie in the Bathurst area in the early 19th Century. He was a hero whose story parallels that other great hero of the underdog, Braveheart. Yet, I wonder to myself, everyone knows about Braveheart, why have I never heard of Windradyne? Clearly more work needs doing.