White Noise explored 'abstraction in a digital age' – specifically, how contemporary artists are using the language of abstraction – as developed in the twentieth century – within the context of the digital moving image. Located downstairs in the 'black box' screening gallery, eight international and Australian artists were showcased, accompanied by an online component, screenings from ACMI's collection, and a large catalogue.

The catalogue and screenings linked the exhibited work to early abstract film experiments, the history of the monochrome and concepts of interactivity and complexity. But there was one 'missing link' to the exhibition, one much more banal, mainstream and closer to home: namely, the paradigm of the screensaver (the Mac OSX comet swirls is a recent classic). This clearly wasn't a screensaver show, but each work in White Noise behaved like a screensaver with a twist, and it was the twists that made the exhibition captivating.

In the main exhibition component, the twists were a question of the installation rather than the screen content. The first room gave a subtle clue to this. In Black on Black, White on White by Jonathan Duckworth (from Metraform, Melbourne), three small, horizontal screens displayed a simple vector graphics pattern, but only the middle one was obvious. The pattern could only be seen on the other two screens by squinting from certain angles. This was due to Polaroid shields covering the screens, thus foregrounding the spatial and material qualities of the screen.

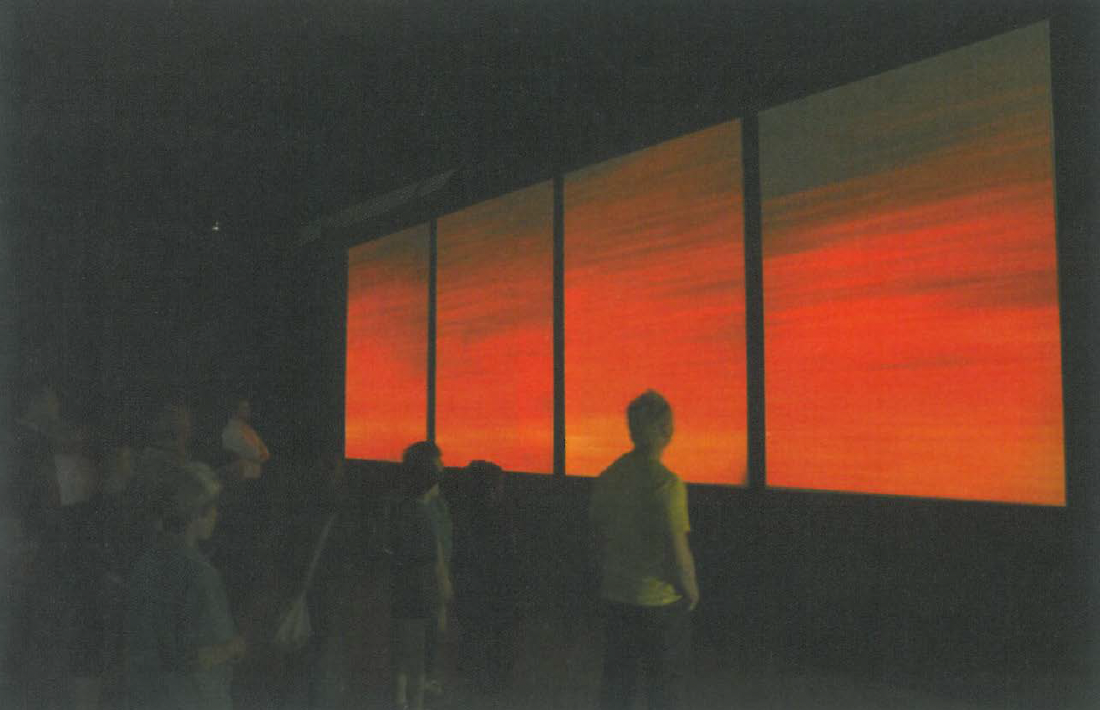

In contrast, Ulf Langheinrich (Austria) presented two cinematic essays. Waveform was a large four-panel work that confronted the viewer with glowing red bands that looked like an ambiguous land- or sea-scape. Drift, commissioned by ACMI, was an even larger two-panel work that hurtled the viewer across a sea floor that slowly morphed into film grains and then into hypnotic white bands, with a puzzling cut to an octopus.

Ryoji Ikeda's data.spectra was also a room-sized work, but with a screen only twoinches high – a strip of white light that was, on closer inspection, rows of scrolling Matrix-like digits. Ikeda's other work, spectra II, wasn't concerned with the moving image, which made it an odd, though startling, addition. A long corridor with alternating bright light, strobe light and black outs made it the most extreme sensory experiment of the exhibition.

Aguas Vivas by Peter Bosch and Simone Simons (Holland/Spain) appeared to be the most sophisticated digital screen work – a dazzling set of organic forms that danced on screen chaos-theory style. But a hole in a nearby wall revealed a simple analogue set up: a real-time video of reflections of a fluorescent light on a vibrating tub of oil. An object lesson that generative software coding still lags behind the nuance and variation possible with clever analogue processes.

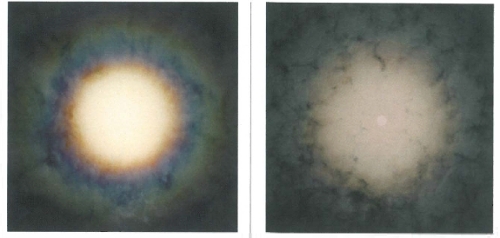

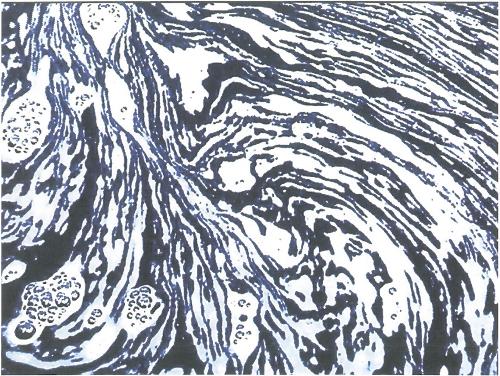

Keiko Kimoto (Japan) also (perhaps unwittingly), showed the gap between digital and analogue technologies. Imaginary Numbers was a series of galaxy-like patterns displayed on luminescent plates and a plasma screen. The plates had a far greater black/white contrast and a far finer resolution, so much so that the plasma screen seemed the older, weaker technology.

Less convincing was Absolute 5 by Ernest Edmunds (Sydney) and Mark Fell (UK). A screen of coloured stripes, positioned above head height with surround-sound glitch-music, it promised an 'interactive system' that was difficult to discern. Electronica sound was part of most of the works, acting like a general immersive glue, rather than carrying any specific symbolic or structural content.

Accompanying the installed works was an online section from the Abstraction Now exhibition held in Vienna in 2003. Experienced via PC, these digital vignettes functioned like interactive screensavers that changed shape, sound, size, colour, density, etc. on the click or drag of a mouse.

Finally, one of the strongest works was the exhibition layout itself (by Studio 505 and The Flaming Beacon), a play on digital screens and abstract space. In the darkness, square doorways of blue light separated each room and framed LCD info screens, and from either end this created the optical illusion that one was in a mirror hall. The layout also solved the issue of audio and light spill between works.

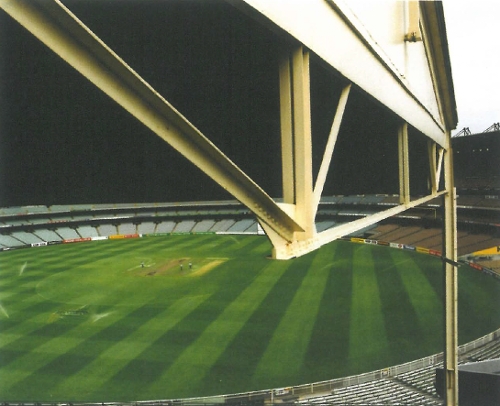

However, there were some problems with the framing and layout– the locations of both catalogue and screening room, which together bore much of the weight of the curatorial narrative, were poorly signed. There was some sunlight spill during the day, and Langheinrich's circular work Light was awkwardly spotted next to escalators.

White Noise achieved impressive production values in the presentation of immersive digital works, setting a benchmark that befits a national centre. It showed the digital screen saved from a life of image only, entering via abstraction, into installation.