Sex, scandal, murder and mayhem; painter Adam Cullen's solo show Maintaining the Rage is like channel surfing through the best of bad TV. Cullen dishes out a wild combo of scandalous news, B-grade horror and tabloid telly, all painted in his manic signature style of vivid colours and furious brushstrokes. His paintings are saturated with the international language of pop culture in a parochial Australian context; a brief moment before the free trade agreement with the US really kicks in and all the bad Aussie soaps and insipid dramas become just nostalgia-tainted relics of the past. In Maintaining the Rage we still get some local content.

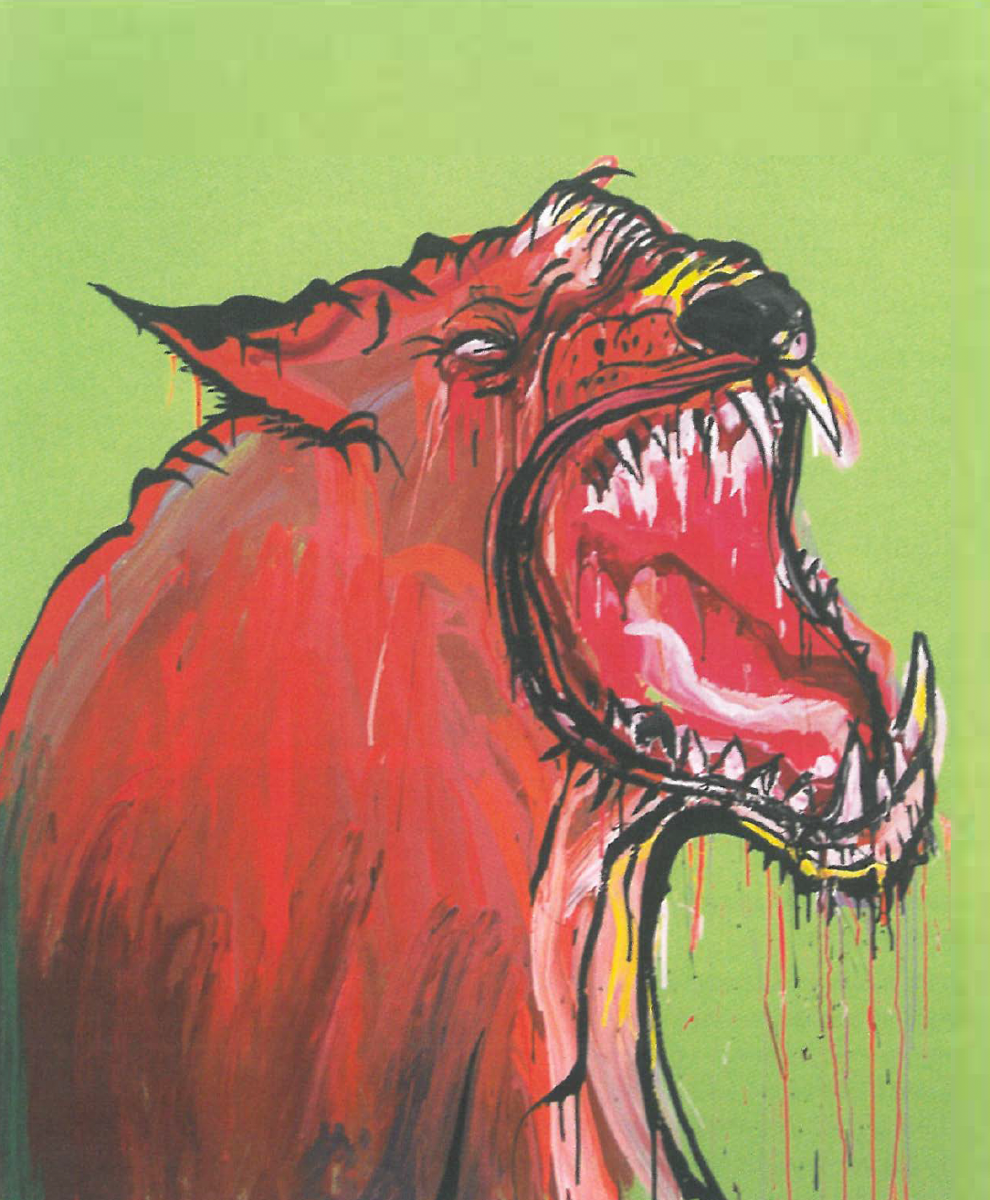

In Cullen's wild paintings, Indigenous road kill casualties are reanimated for bit parts in a hypothetical Aussie remake of Night of the Living Dead. In God Joined the Mob and Left his Cat Behind, a mutant beast (part Tasmanian devil, part cat, part dingo) howls with rage and frustration against a lime-green background, while dripping fluorescent paint from his pointy fangs. In Nothing's Ever Yours to Keep, a deformed kangaroo stumbles across the canvas like a stunned zombie critter. Judging by the grim fatalism of the title, it seems that this battered kangaroo is suffering not from a collision with a car, but from a more devastating emotional crash. In lines scrawled across the painting's bright red surface Cullen writes, 'Every night she comes to take me out to dreamland and when I'm with her, I'm the richest man in town&'. It is not clear who 'she' is. An ideal? An intoxicant? A flesh-and-blood woman? The mythical 'she' of she'll be right? But like a palimpsest, further stanzas of the poem are barely visible, wiped out with streaks of yellow paint and fading into the red background. This painting fairly oozes trauma; it seems that Cullen left things unsaid – or maybe said too much.

Cullen's show takes us on a tour of Aussie angst, a kind of late-capitalist, post-feminist, post-postmodern ennui. In Bongos, Cullen depicts a reclining bodacious babe and his dribbling text announces: 'I was thinking of becoming a wino and playing bongos full time'. This painting conjures up the ghost of Charles Bukowski (or his Hollywood incarnation Mickey Rourke) as a role model for creative self destruction. But you sense that Cullen is just kidding – dropping out has ceased to be an option. When counter culture is absorbed and relentlessly marketed by the mainstream, and 'alternative' is a pop genre that sells millions, where is there to go?

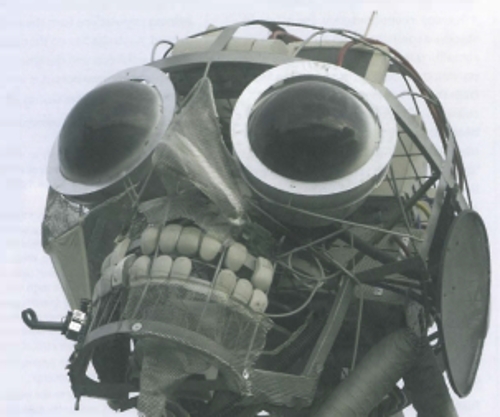

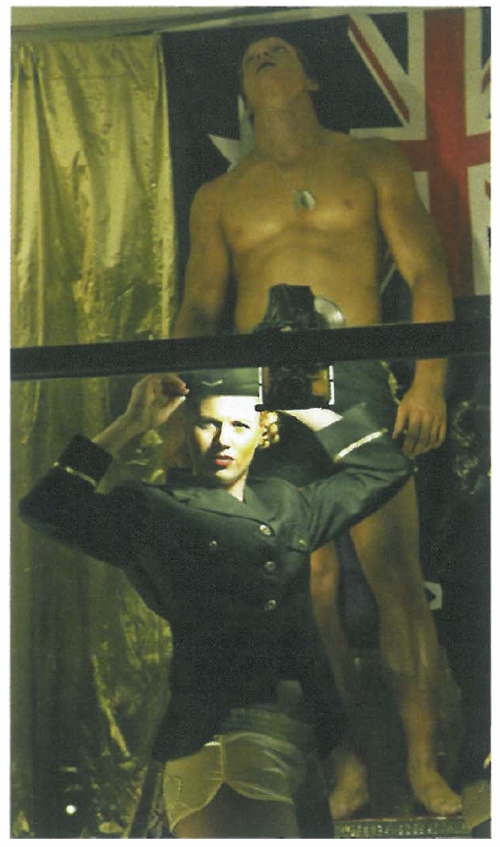

The post-post parallel universe of Cullen's paintings is mired in a pop culture where political correctness is well and truly dead. His women are all bikini clad and seem to be modelled on stills from old Bond movies. In these paintings, there's no middle ground between being a machete-wielding harpy or a helpless buxom wench, bound and gagged. In The Horror She was Unleashing, a testosterone-fuelled babe wrestles with a shark; Cullen's women oscillate wildly between having too much agency or none at all. And the men don't fare much better. In fact, Cullen's men are behaving very badly. Like sound bites lifted from CNN, they are all up to no good. One is a home-grown thug in a flannelette shirt, desperately clutching the classic smoking gun; the other is a diabolical pontiff with glaring red eyes. Cullen's demented cleric looks like a cross between the wrinkle-headed alien in ET and one of Francis Bacon's smeared popes caught in a perpetual scream, his mouth forms an O of glee as he approaches his helpless female victim.

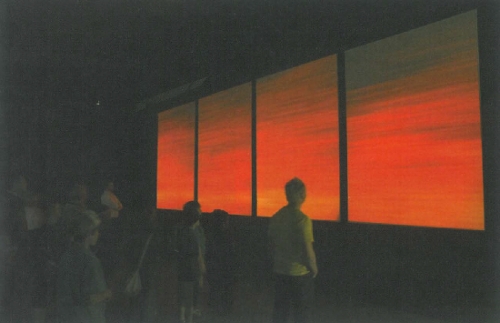

While many of Cullen's previous works have had an overtly political edge, the paintings in Maintaining the Rage present a tragic-comic vision saturated by pop culture. They reflect a society that has been mainlining TV; its eyes dilated into blank squares, teetering on the verge of overdose.