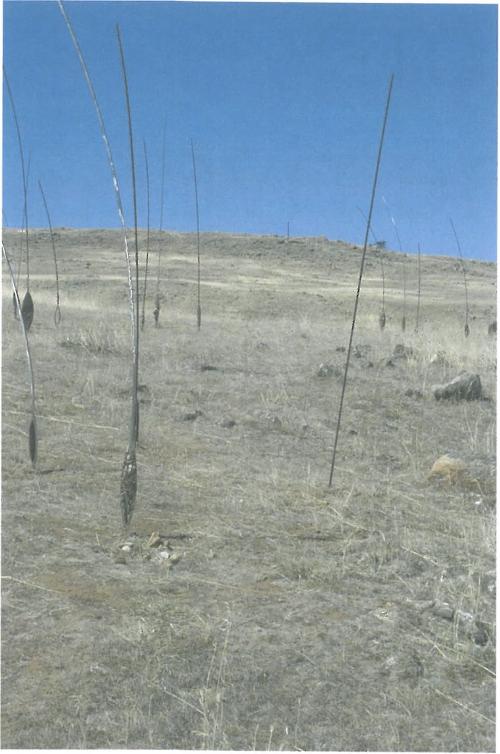

Installations that involve subtle interventions in an outdoor space must surely be one of the bravest of art forms. The artist's work may be totally overlooked by a significant proportion of its potential audience. Even the more observant viewer may be seriously challenged by the nature of such a minimalist approach.

Trudi Brinckman's White Plastic Cup doesn't intrude into the great block of air hemmed in by the towering historic sandstone walls of Kelly's Garden. On first glance through the entry gates, the pebbled courtyard appears empty. It takes a degree of curiosity to venture inside and discover the scattering of water-filled disposable white plastic cups embedded in the courtyard, their rims flush with its surface. Confronted by this seeming lack of substance, it's hard to resist the urge to turn on the spot, to search for more.

Here is the crucial moment when experiencing conceptual installation work of this kind. A split-second decision by the viewer will determine whether they take on the challenge of engaging further (and only by doing so can they hope to gain some insight into the nature and meaning of the work) or to dismiss it as 'too hard', and to walk away. In a time-pressed world it is so easy to walk away from something that doesn't offer a quick hit. Yet the secret to reaping the rewards of White Plastic Cup lies in allowing it to seep into the subconscious as you explore and savour its presence.

A tour of discovery reveals a multitude of miniature watery worlds. Their small size and lowly location seduce the viewer into a crouching intimacy to better view the contents of each cup. They have leaves, wattle blossoms, a sediment of dust, feathers, scraps of paper, or captured and drowned insects. Each cup has uniquely sampled the world, gathering the offerings of the wind. Like mortuary vessels they serve as final resting places.

Brinckman has clearly embraced this weather-activated process, but may not have anticipated the level of human interaction. Some of the cups have been trampled over and lie uncomfortably crushed and twisted. Is this accidental, a consequence of such a disposable piece of 'rubbish' not being recognised as part of an artwork, or is it a pointed statement by a passer-by on the audacity of offering plastic cups as art?

Some are totally or partially filled with the surrounding pebbles, perhaps evidence of someone's playfulness – a game of tiddlywinks? The appearance of the work, and the way it entices you down to ground level to explore small things, evokes long-forgotten childhood experiences.

Re-viewing the installation as a whole, my attention settles on the surfaces of the cups' water. The way the wind and (to my surprise) the passing traffic cause them to vibrate, the way they reflect the light. These meditations lead to thoughts on the value of water – the source of all life. These thin plastic cups, so vulnerable in the surface of the earth, tremulously holding a few mouthfuls of water, seem suddenly emblematic of the perilous position humanity currently finds itself in.

Brinckman has a self-confessed fascination with water – with its materiality and meanings. A visit to West Africa some years ago was pivotal in developing this interest, where she witnessed the preciousness of its substance and the importance of its containment. White Plastic Cup seems to synthesise these concerns.

Brinckman offers the most fragile and humble of containers filled with the most fundamental of substances. This union of cup and water creates an almost spiritual dimension to an installation that has transformed Kelly's Garden into a quietly reflective space. It's an experiment in pared-back simplicity and a courageous one at that.