What does the onset of climate change mean to an artist today? We have known about species extinction for decades, and the death of ecosystems; artists whose work evolved around these issues first emerged during the sixties. Newton and Helen Harrison in the USA were some of the first to zero in on ecology as the central issue of our time[1] while the work of US-based pioneer biological artist Eduardo Kac[2] in the area of genetic code (remember his infamous green-glowing rabbit?) took us to the very edges of creation. The long-running SuperWeed projects of British artist Heath Bunting[3] are now moving him and his activist colleagues into the front line of environmental battle in Europe's agricultural border zones.

Getting to grips with the idea of ecological systems as art, not in the traditional beaux-arts tradition of metaphors or parallels but as the substance of art practice itself, has started to become the daily business of more and more artists around the globe (see www.greenmuseum.org). There is a great variety of ways of approaching this, from 'land art' to working with natural forces like weather to ephemeral 'art in nature' installations[4] or even remediation and waste management as art. As the global ecological crisis shows signs of approaching a catastrophic tipping point, artists around the world are increasingly becoming passionate and effective campaigners for change through their ability to graphically illustrate the disaster that is unfolding around us.

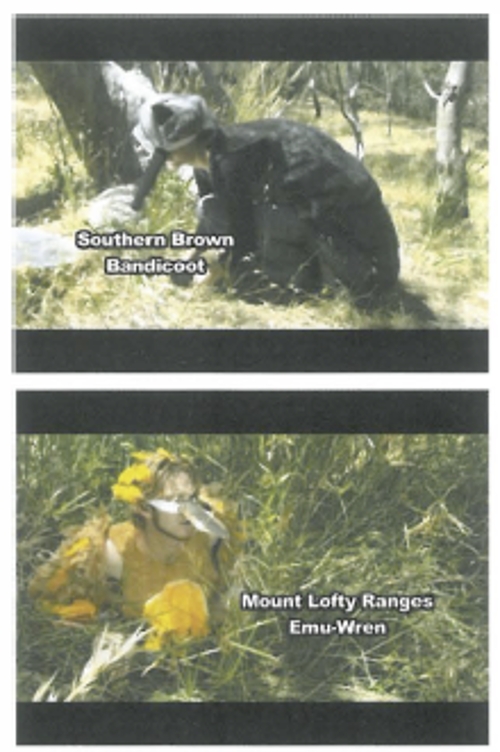

Zooming in on Australia, it is clear that whereas in the 1890s the landscape painter Eugene Von Guérard perceived sublime mountains and vistas of wilderness forests, his counterparts today see salinity, drought, wild storms, loss of habitat, the extinction of untold thousands of species and the death of rivers. How they choose to 'write' this in the form of art is the stuff of this issue of Artlink.[5]

In their efforts to understand why nature has moved from divine inspiration to basket case, artists realise that though they may play some part in helping to turn things around, they may also be part of the problem. For every artist who works in Andy Goldsworthy fashion to avoid negative impact on the planet, there are millions who are part of the sizeable growth industry which is the commercial art market. But in this liminal time there are arguments to support short-term impact for long-term goals so that it is possible to explain why a well-known 'ecological' painter like John Wolseley[6] might credibly justify ending up at the expensive end of the commodity cycle because of the positive effect his work has in educating people at many levels of society.[7]

Our global ecological footprint is a rough measure of personal impact on the world ecosystem. We know that the footprint of the average citizen of India is a tiny fraction of that of the average Australian. This is simply because relative poverty prevents participation in the destructive cycle of production, consumption and waste which is the normal condition in 'advanced' economies. How the artworld stacks up compared with other sectors is something that is rarely discussed. Figures proving that most artists earn very little from their art might make us feel less culpable, and certainly the vast majority of artists live very simply compared with the obscene self-indulgence of the real 'spending classes'. Scratch the surface of the figures and you find that some 'poor' artists have another job which funds their consumption of air-conditioning, plasma screens, dishwashers, overseas trips, new computers and petrol. How many artists take one of the ecological footprint tests?[8] Even the more frugal and responsible recyclers, cyclists or vegetarians will be shocked to find how many planets we would need if everyone on earth lived like we do.

Turning to the high end of the sector and the art fairs, conferences, biennials, art museums and galleries, art prizes and glitzy events held and paid for with private and public money in the name of culture, we are moving up there with the baddies of the corporate world.[9] Larger salary packages tend to mean more consumption, more disposable income, more depletion of scarce resources, more waste and of course more greenhouse gas emissions.

Artlink itself has been navel-gazing and with our printer Finsbury Green (see article p73 this issue) we have found that there are ways to balance out the negative impact of the resources used in printing.[10]

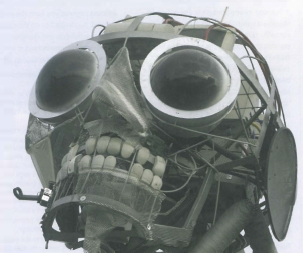

In London the venerable RSA[11] has invited artists to address ecological debates in public with its current Art & Ecology project. Recently two of their members[12] devised the WEEE Man, a seven metre tall sculpture of an incomplete body which stood on the South Bank for a month. The Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Man, weighing in at 3.3 tonnes, equals the quantity of whitegoods, computers, TVs, small appliances, home power tools, telephones, sewing machines, lawnmowers etc the average Briton consumes during his or her lifetime. Consumption of these items in the EU is on the increase with 90% still going to landfill. An analysis of typical patterns in Australia today would show that the vital statistics of an Aussie WEEE Man would be possibly twice as large.

The art and architecture we produce as a society has always been a barometer of the health of the society. In the face of ecological collapse, art is being pressed into helping populations turn their attitudes around. Australia has no shortage of artists, architects and designers who are environmental warriors. It is up to us to listen to what they are saying.

Footnotes

- ^ www.greenmuseum.org/content/artist index/artist_id-81.html

- ^ Kac visited Adelaide recently to show work and run workshops on live/biological art. See Niki Sperou in Art/ink Vol 25 no 3 p87) and www.ekac.org

- ^ Ongoing projects by Heath Bunting and Kayle Brandon include N atural Reality Superweed, which threaten to unleash a breed of 'superweeds'. Their Borderxing project entailed hiking across the 'green border' between dozensof European states, an often high risk form of practical resistance to the growing power of police and border guards over our personal freedom of movement. {from www.thersa.org/arts/conferences/conference1/ecoConference.asp)

- ^ See the Artists in Nature International Network: www.artinnature.org/

- ^ I am extremely grateful to the many scientists, environmentalists, architects, ecologists, educators and m embers of governmentdepartments of sustainabil ity, zero waste and greenhouse as well as all the artists and curators who have advised in the research phase of this issue of Artlink

- ^ see www.johnwolseley.net

- ^ other examples of this debit-credit equation are eco-architects who travel to international conferences and bring back knowledge to local communities which result in net environmental gains

- ^ eg www.myfootprint.org

- ^ Very few studies have been done on theenvironmental impact of various industrialsectors in Australia

- ^ To complement this, Artlink's newly redeveloped website will move the magazine gradually towards more on line content

- ^ see www.thersa.org/rsa/arts/programme.htm. The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce - commonly known as the RSA - was founded in 1754

- ^ The idea behind the WEEE man was conceived by Hugh Knowles and developed in partnership with Mark Fremantle, both Fellows of the RSA. It was designed by Paul Bonomini, unveiled atLondon City H all Concourse, 29th April 2005, and is now touring the U K. It is an environmental awareness initiative from the RSA, Canon Europe and Reco-Vie Recycling