A well-constructed retrospective must bring together an artist's most recognisable works but should also reveal some surprises. Vivien Johnson has assembled Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri's most ambitious and previously published works, as well as uncovering remarkable early carvings and several of his last compelling canvases. The former confirms the artist's extraordinary spatial intelligence while the latter offers a frightening and uncharacteristically introspective gaze into his mortality.

A sustained and masterly focus on spatial representation of land and ceremony makes Clifford Possum the right choice for this the first retrospective of a Papunya Tula artist at a state gallery. The clarity of construction of this chronological show reinforces the defined phases of Clifford Possum's practice and draws focus on his crucial and singular relationship to the burgeoning market for Aboriginal art. Curiously, descriptions of the paintings were not included as wall texts at AGSA, truncating the artist's clear intention that the works communicate detailed information about country and ceremony to a non-Aboriginal audience.

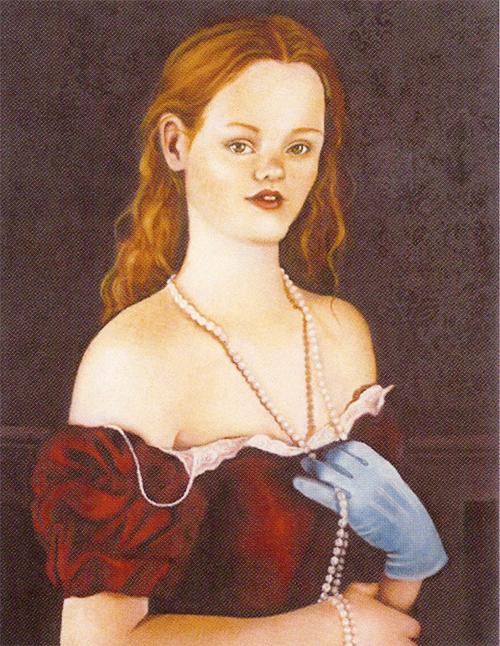

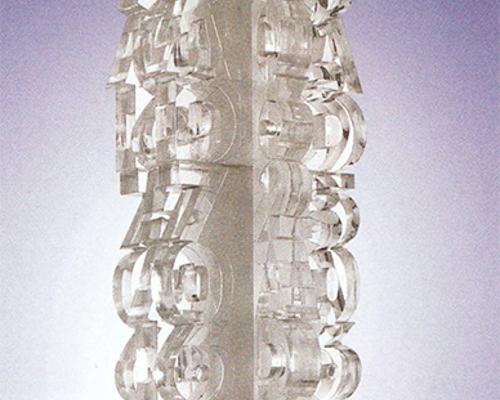

The introduction to the exhibition includes two carvings; in each a snake is released from the forked limbs of a bean wood tree. Just as a fine carver works to the exact dimensions of a block of marble, the young stockman reveals the tensile relationship between the limb and the snake. The conceptual purity of these works is a precursor to Clifford Possum's unparalleled skill in conjuring objects in space, describing the physical relationships below, above and beyond objects.

In 1972 Clifford Possum was introduced to the emergent painting movement at Papunya by his cousin Kaapa Tjapitjinpa and brother Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri. As an occasional visitor from Narwietooma (cattle station) to Papunya, Clifford Possum made his pictorial ambitions apparent in his initial and extraordinarily ambitious works - Emu Corroboree Man and Honey Ant Ceremony. During the first few years as a painter he leapt from one spatial essay to the next. Often inspired by other artists, Clifford Possum brought a new visual rigour to the work of the Papunya artists, gradually building a lexicon of signs and developing methods that came together in the great cartographic series of the late 1970s.

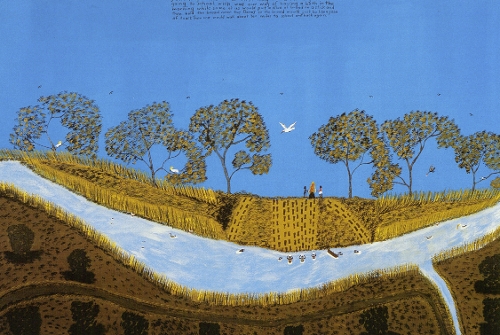

Beginning with Warlugulong - a delicate and infinitely detailed collaboration with Tim Leura - Tjapaltjarri's project to map his country continued for three years, culminating with his production of Yuutjtutiyungu, the most complex and ambitious work attempted in the Western Desert idiom.

This series of five monumental canvases make manifest the conceptual maps that underpin the Aboriginal understanding of land in central Australia. They are synoptic works in which the artist displaces the iconographs associated with many individual Dreamings in exact geographical relationship to each other. Sites are joined along criss-crossing ancestral songlines with precise representations of the tracks and traces left by ancestral beings. Across these vast canvases, each representing hundreds of square kilometres of country, the principal soil and vegetation types are mimicked with patches of dots representing the country as understood from above. The production of these works required an extraordinary knowledge of country, the activities of ancestral heroes as well as sheer technical virtuosity. As a group they stand as one of the most remarkable achievements of the Aboriginal cultural renaissance of the last thirty years.

Having presented such an encyclopaedic depiction of his country Clifford Possum narrowed the geographic scale of his works to create paintings in which the signs and traces associated with one or two Dreamings were elaborated to configure compelling and astonishingly tight representations. Over the next decade the artist created numerous perfect works, including Yuelamu (Honey Ant Dreaming), Hare Wallaby and Possum Dreaming in which spatial clarity, pattern, a heightened palette and story come together in dazzling compositions. The technical virtuosity of the series tends to seduce the eye to the extent that the underlying conceptual power of the paintings is almost masked by the scintillating beauty of the surface. These are the works that brought the artist to national and international prominence; they were a tour de force that could no longer be ignored by a contemporary art market eager for the next new wave.

The late 1980s saw Tjapaltjarri move from his outstation at Mbunghara to Alice Springs and beyond, and he began to work independently of the Papunya Tula Artists cooperative. While this phase of the his life had its moments artistically, it unfortunately reveals more about the rapacious nature of the art market expanding across a rich new cultural frontier than it does about Possum's unique artistic vision. For over a decade the artist was feted by a series of entrepreneurs as he tried to satisfy the social obligations that came of being a highly paid star in a poor community fuelled by grog and chaos.

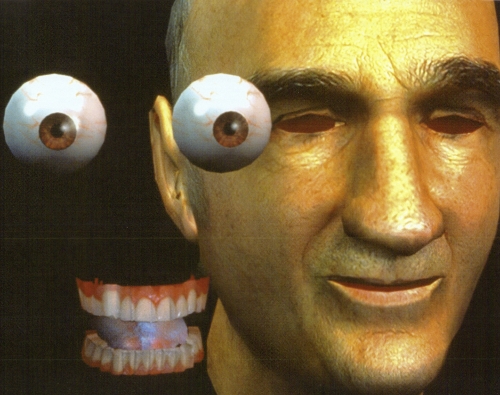

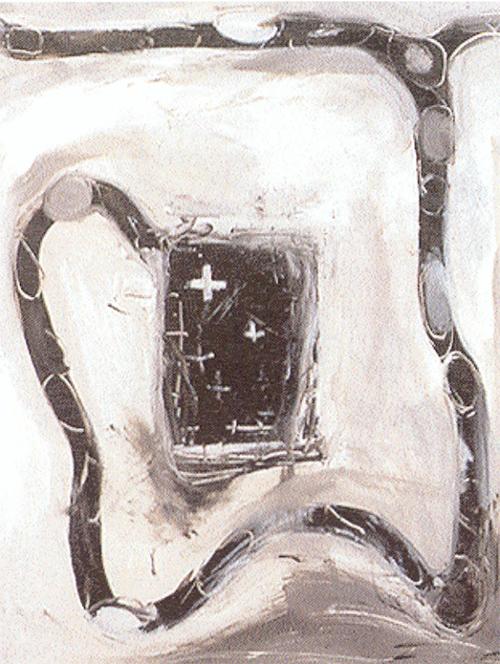

His last stark canvases feature skeletons talking to each other on ground stained with paines grey. These are prophetic and uncharacteristically psychological works. They pose disturbing questions about the deeper meaning of the cross-cultural experiment that had Clifford Possum, his family and the Aboriginal art market at its epicentre.