This is a disconcerting exhibition. In the best possible way. And not in the way that might be first apparent.

For there is plenty of evidence that even the rank-and-file gallery goers of Brisbane are more-or-less familiar with art that has origins in cultures from the Asia-Pacific region and beyond: this exhibition ran to coincide with another exhibition titled Brisbane Buddhas, curated by Louise Denoon, featuring an extensive range of Buddhas that were borrowed from a variety of Brisbane homes.

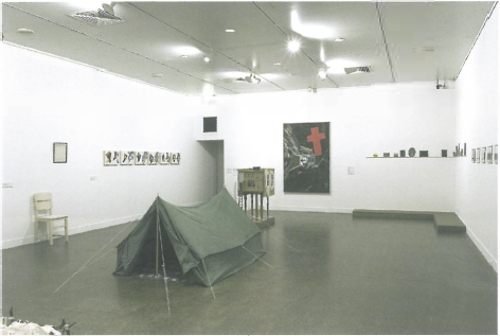

Situated in the gallery space across from this, the works in Echoes of Home seem slightly too cramped beneath the black ceiling and the heavy brown of the parquet floor. While this sensation of claustrophobia could have something to do with the physical installation of the work, it was also contributed to by the weight of ideas and possibilities and disjunctures between the individual pieces.

As evidence of the MoB's commitment to investigating the cultural diversity of the community, the exhibition features the work of Asian artists who have made their home in Australia. The theme of cultural diversity and the complexity of contemporary art in the region is one that is gradually finding focus in smaller, more focused exhibitions that are able to bring a more intimate, considered approach to this vast region of cultural production and intellectual speculation.

And although curator Christine Clark has chosen the general theme of 'in-between-ness' to bring these works together, she side-steps the trap of providing a new category of definition for the immigrant artists, and instead uses it not only as a means of getting through the hubris of defining art production according to national representation, but also as a means through which the exhibition can include the work of artists, craftspersons and designers.

The excellent and beautifully produced catalogue that accompanies the exhibition introduces insights into these disjunctures that are more located in theoretical and taxonomical terrains than geographic. The presentation of the curator/editor's essay alongside an abridged version of Sue Rowley's 1999 essay titled Craft, creativity and critical practice manages to begin to gently prise apart some of the assumptions that we have come to associate with exhibiting the work of artists from the Asia-Pacific region.

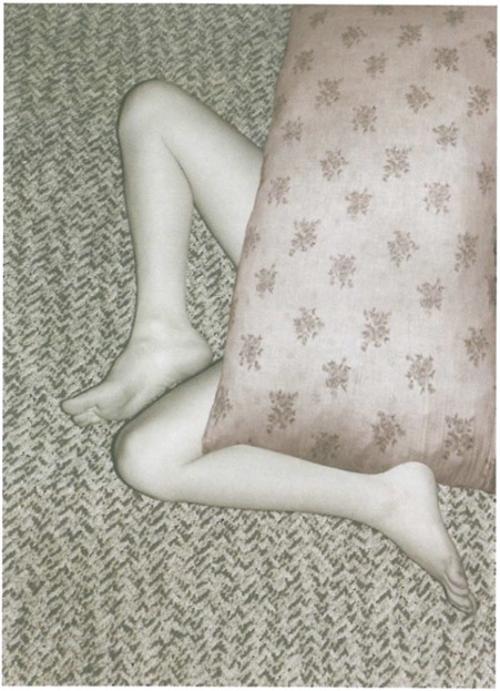

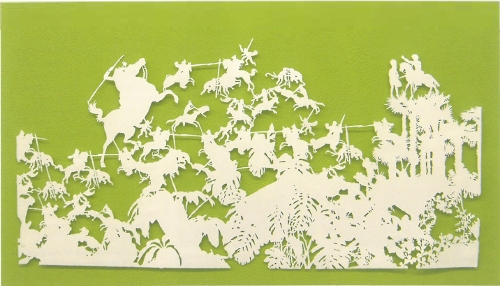

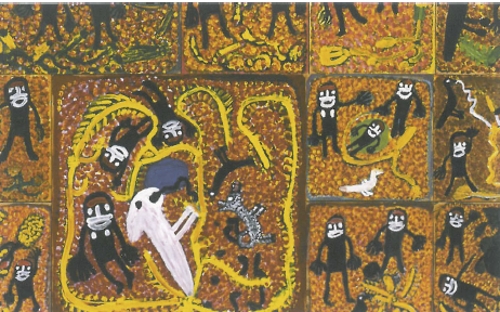

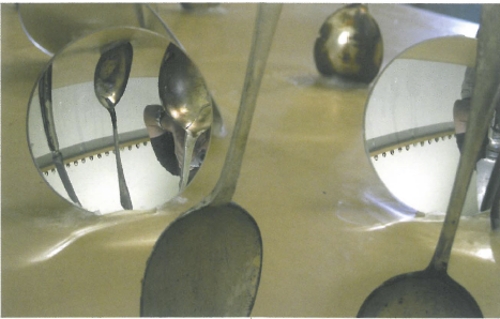

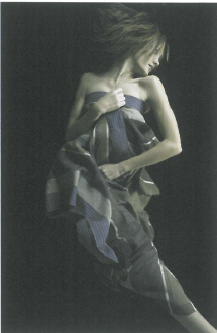

In turn, by implication, the work is re-presented within a framework that refuses representation limited by the dualisms of craft/art; tradition/innovation; conservatism/modernism and so on. Within this curatorial framework, well-known artist Dadang Christanto's delicate clay and paper installation commemorating the massacre of minority groups in Indonesia during 1965/66, titled Daun-daun yang menangis (The leaves that cry) is represented alongside the work of fashion designer Alistair Trung, whose philosophy on garments relates them to three layers of protection needed by all humans – skin, clothing and shelter.

If we have difficulty in drawing relationships between these outcomes of cultural production within the one exhibition, there can be little doubt that the barriers that stand in our way have in no small way formed from the failure of western modernism to understand the continuities between tradition and innovation. As Sue Rowley points out, the creativity of artworks should disrupt the boundaries set by institutions and assumptions. When this happens, the viewer is called upon to respond to such challenges, and to search for new ways of thinking about cultural production that re-scribe rather than pre-scribe social interactivity.

It is within such considerations that this exhibition issues the most vexing challenges: no longer do the works look simply exotic, and for no longer can it be assumed that this is art production that takes place outside the tempero-spatial references of modernism. Rather, assembled in this way – with a knowing heedlessness for the conservative categorisation of international contemporary art – the exhibition seems to call for a reconsideration of the ways in which we structure our thinking about what might constitute transformative cultural practice.