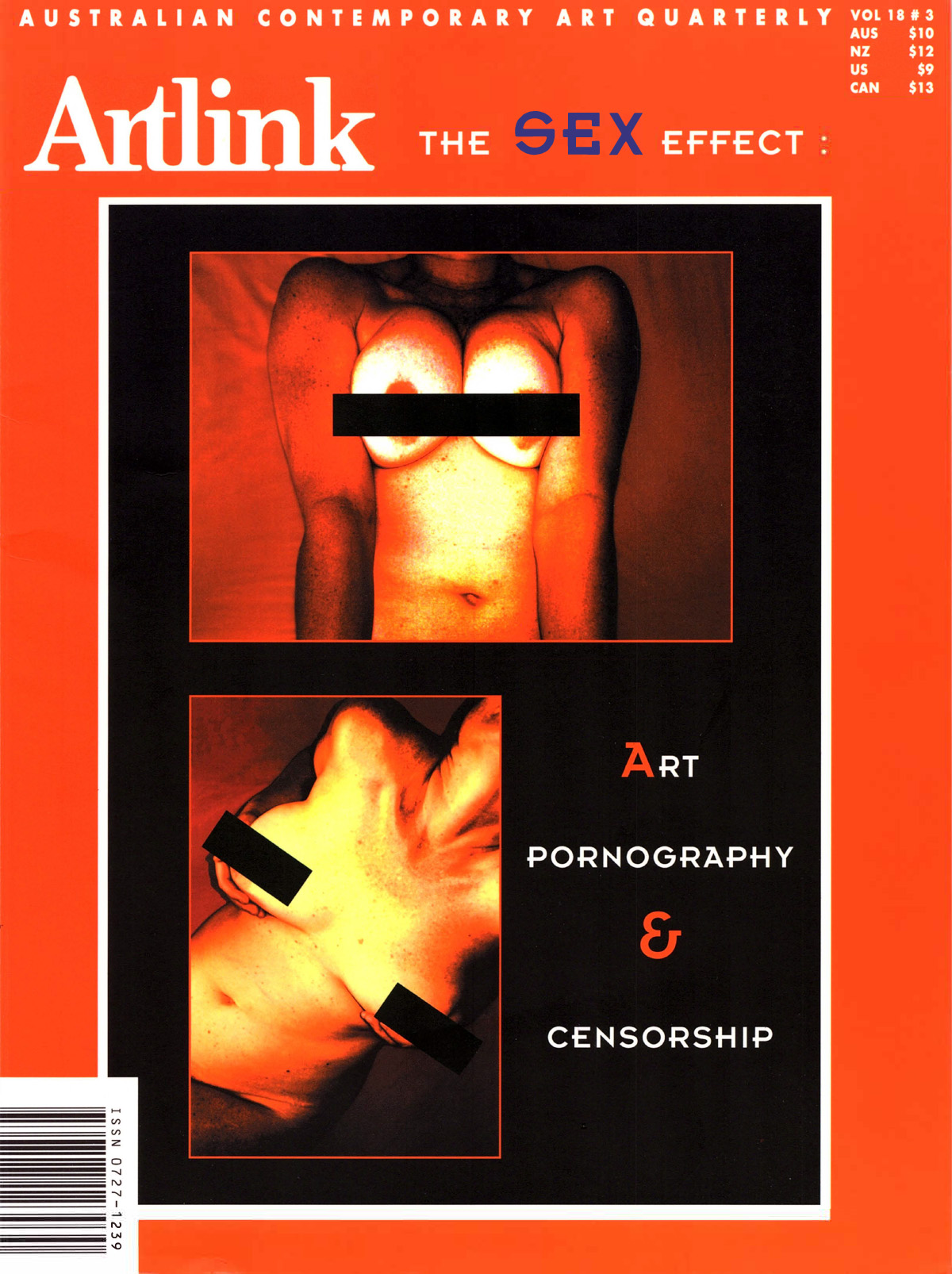

Art, Pornography & Censorship

Issue 18:3 | September 1998

Guest editor: Dr Robert Crocker. The conflicts created by centuries of suppression and the demonisation of sex and sensuality are a heavy burden for all of us in the West, whatever our views on pornography or censorship. Explores the 'sex effect' in contemporary art. Is the freedom of the art world under threat from creeping conservatism? The laws of censorship and self-censorship, court cases, community standards and 'family values', photography the Warhol time capsules, feminist positions.

In this issue

Visual Culture, Pornography and Censorship

Editorial: hypocrisy in our attitude to sex. It is both celebrated and maligned, and the censorship laws allow young people to view explicit violence while classifying sex for adults only, based on psuedo-scientific analysis of 'normal' or 'aberrant'. This history of public attitude from the Enlightenment on, libertinism a radical opposition to status quo, advertising and porn, and artists exercising self-censorship.

The Prying Game

Explores the difficult issues surrounding artistic expression and censorship (both self censorship and public) with the associated threat of legal action.

In the Middle of it All - A Personal Text

From the perspective of one who has worked on the SA Classification of Publications Board. Argues that censorship is becoming increasingly unmanageable due to two trends which are detailed in the article. Also argues that public debate (with the exception of child pornography) in the media has declined. In contrast there is rising debate about sacrilege.

Censor and be Damned

Julie Robb is the executive director of the Arts Law Centre of Australia. The centre advises artists and those involved in exhibitions and publication of risky material of the cultural responsibilities to make efforts to find ways of exercising their privileges. Looks at the current practices.

Dying Frightened: Gasps of Old Men in Suits

Explores the nature of censorship, how it is applied and the consequences of repression in artistic expression. Analyses the issues from a feminist perspective. "Censorship is about as effective as prohibition". Examines the censorship applied to the exhibition by Jasmine Hirst.

Porn Again

Porn is a safety valve, big business, a cabinet of curiosities, a staging theatre for many contradictions and inversions: male submission, female dominance, intricate identity and gender crossings, and the validity of female desire. Pleasure is misunderstood in a society where is commodified, exchanged and consumed displaced into food, wine, cars....Discusses the works of Jane Burton, Mary Fallon, Catherine Mackinnon, Marcia Pally and W.H.Auden.

Andy's Idol

Analysis of some of Andy Warhol's early works to demonstrate a direct link between his art and the homoerotic magazines which the author found in his Time Capsules in the archives of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, USA.

In a Barbie World

Fictional Barbies (Mattel trademarked doll) are presented in the dark side of suburbia spinning a queer identity for Ken and Barbie.

Some Notes on Pornography, Contemporary Art and Social Politics

Explores the 'pornographic' in the public domain. Art isn't an excuse for pornography, because pornography simpy exists. Art has remained a realm within which a vast range of ideas can be explored and tested. There are no questions of ethics or morality in art. This starts to get more exciting as art gets closer to life.

Subject Declined: Swap Mail with Francesca Da Rimini

Explores Francesca Da Rimini's web site 'Dollspace' - extracts of an email interview.

Lollies and Legends

The artist writes about his work and his influences. Explores issues of self censorship.

Masculinity Below the Surface: Pornography and Suppression in Images of Broken Hill Miners

Mines and mining provide underground settings for a sub-genre of gay male porn. Features the work of artists George Gittoes and Avis Smith.

Fetish: So what's your Fetish?

The artist writes about her interest in feminism and much of what is written seems intrinsically fetishistic. Her aim was to try to create a democratic, woman friendly fetish language.

Crossing the Fine Line: The Case of Concetta Petrillo

Photography has inspired more hysteria and censorship than paintings .... examines the situation in Perth Western Australia with child pornography and the photographs of Concetta Petrillo.

Garden of Earthly Delights: Erotica at Carrick Hill

Gone from Carrick Hill before it became a public collection are three Stanley Spencer erotic paintings and William Dobell's 'The Duchess Disrobes' (two versions). Smith examines the nature of the collection of works by Sir Edward and Lady Ursula Haywood.

The Spectre of Pedophilia and Dennis Del Favero's Parting Embrace

Dennis Del Favero's 'Parting Embrace' is a series of 10 Type C prints which attempt to investigate the subjectivity of sexual abuse in a way that not only engages with its inherent pornographic content but which refuses neat moral resolution.

Political Pop-porn in Hong Kong

Much of the vibrancy of Hong Kong's contemporary culture manifests itself in unexpected new forms...explores how four artists construct images of sexuality within the compact (post?) colonial environment.

An Accelerated Life: Lydia Lunch

Women need to fight for an alternative pornography. Women need a pornography that addresses all the alternatives of our sexuality, in every format, so that there's something for everyone....Farmer interviewed porn star Lydia Lunch on her visit to the MRC in Adelaide.

The Museum, the Muslim and the Infidel: K L Revisited

Critically looks at the exhibition 'Kecurangan - Infidelity' curated by Dato Shahrum Yub in Kuala Lumpur where 90% of Malaysia's population is Muslim.

8 X Tables by Steve Tepper

Moore's Building, Fremantle

May 14 - 28, 1998

Reviewed by Robyn Taylor

Sustained Contemplative Images: Atlas Exhibition Cathy Blanchflower

Goddard de Fiddes Gallery, Perth

1 - 22 May 1998.

Reviewed by Mary Livesey

The Promise of Fruit: Kirsty Darlaston, Brenda Goggs, Lucia Pichler, Karen Russell

North Adelaide School Of Art Gallery

13 May - 4 June 1998

Black Humour

Curated by Neville John O'Neill for the Canberra Contemporary Art Space.

Tandanya, National Aboriginal Cultural Institute, Adelaide

10 July - 16 August 1998

Cosie: She Decorated a House and Called it a Home

Annette McKee and Helen Fuller Jam Factory Gallery Adelaide SA

16 May- 5 July 1998

The Painted Coast: Views of the Fleurieu Peninsula Coast of South Australia.

Art Gallery of SA

8 May to 16 August 1998

Curated by Jane Hylton

Ecologies of Place and Memory and Time and Tide

Ecologies of Place and Memory (Lauren Berkowitz, Rosemary Burke, Torquil Canning, Lola Greeno, Ruth Hadlow, Sieglinde Karl and Louise Weaver)

Time & Tide (Rowena Gough, Gay Hawkes, Lin Li, Pilar Rojas and Catherine Truman)

Both curated by Bridget Sullivan

Plimsoll Gallery, Centre for the Arts, Hobart

May 22 - June 14 (Ecologies)

June 19 - July 12 (Time)

Artrave