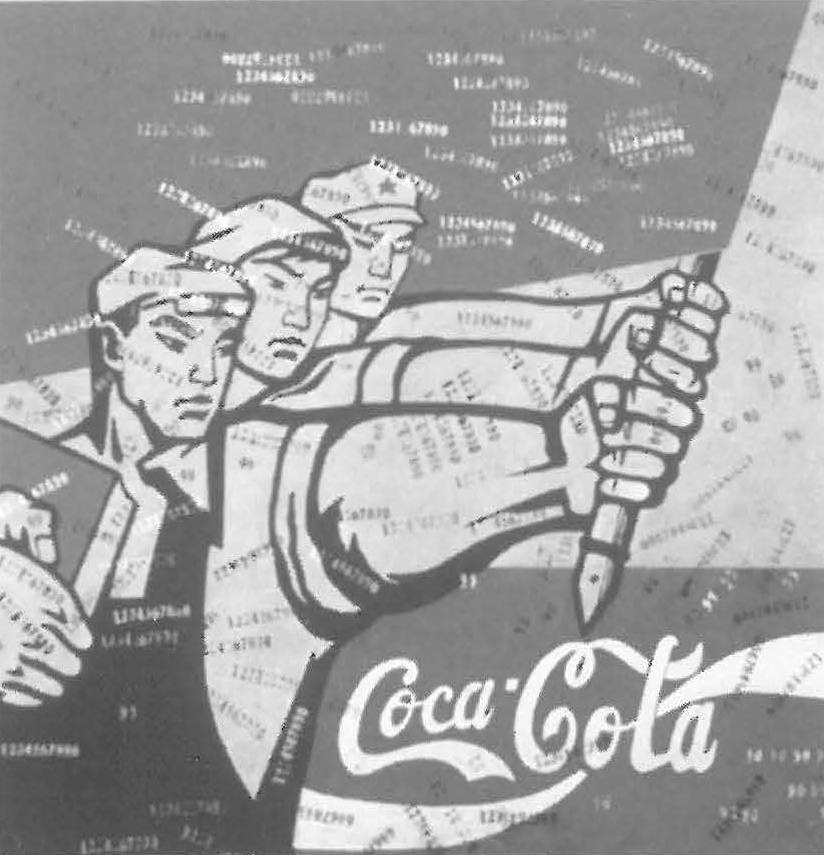

Mao Zedong once hinted that China could do with a dose of upheaval every so often. The 20th century quest for renewal in China can be seen as a series of cyclical revisions as each generation enacts its patriotic commitment in a different way.

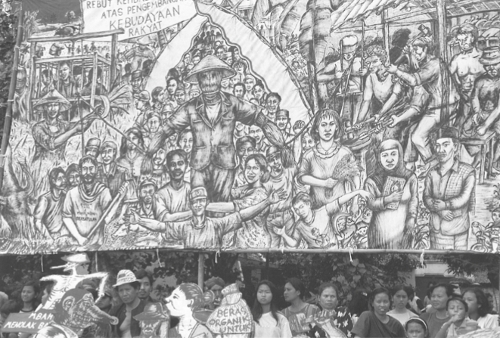

A few weeks before the Tiananmen protests in May 1989, China/Avant-Garde, a huge and unruly art exhibition, took over the nearby National Gallery, gathering together for the first time the products of the hectic experimentalism nurtured in China's art schools since the early eighties and the era of Deng Xiaoping' s open-door policies. The art was lacerating, outrageous and sexy. Copious supplies of condoms and shrimps were distributed to the opening day throng. Then an unlicensed gun was fired by one of the artists as a way of completing her installation and the exhibition was closed down.

China/Avantgarde took place ten years after the People's Republic's first show ever of dissident art was staged on the same site. On that occasion the show coincided with the Democracy Wall movement, which was itself echoed in Tiananmen. Both protests claimed descent from the May Fourth Movement of 1919, when students rallied in Beijing against the humiliating terms of the Versailles Peace Treaty. The heroic spirit of May Fourth pulled in artists and intellectuals of many persuasions and was repeatedly invoked by reformers, whether Nationalist or Communist, as China worked out a modernising destiny of "democracy and science" through the ensuing decades of turmoil.

Gao Minglu, one of the chief curators of the canonical China/Avant-Garde wrote:

... avant-garde artists made the creation of art part of a cultural enlightment programme rather than a formalist activity, a social activity rather than the representation of an illusory reality.

Inside Out is the most ambitious survey of contemporary Chinese art to date. It includes Hong Kong and Taiwan along with the mainland. At its core is work from China/Avant-Garde that was originally directed at cultural transformation within China.

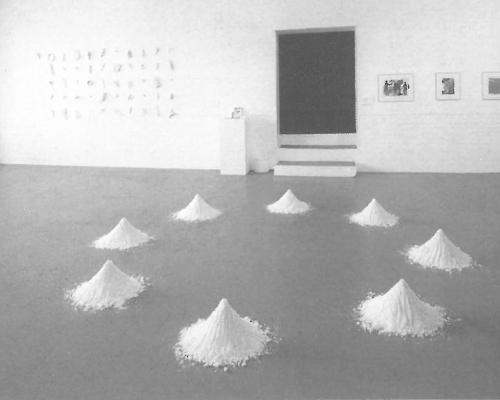

One of the pioneeers was Huang Yongping, whose A History of Chinese painting and "A Concise History of Modern Painting" Washed in a washing Machine for Two Minutes (1987 /1993) reduced two standard art historical texts by Wang Bomin and Herbert Read to a pile of pulp, placed on the museum floor as if to declare a parodic Year Zero for art. Post-1994 artworks have tended to respond, in Gao Minglu's words to, "a shift from an avant-garde targeted on a local political and cultural reality to a neo-avant-garde visuality that strives to transcend local interest in favour of involvement in the international arena."

This situation was anticipated by Xu Bing' s Book from the Sky, created in the seclusion of his studio in 1987. Using traditional methods of woodblock printing, Xu Bing produced dozens of pseudo-Chinese characters; non-existent ideograms, every one of them unreadable to even the most educated Chinese. To readers of Chinese, Book from the Sky is a brain-scrambler. It is as if the Chinese script, the binding essence of the culture, has been turned into an impenetrable wall of mumbo-jumbo in a monumental act of disrespect. For most foreign viewers it remains mute, a devoted revisiting of traditional practice by a contemporaray installation artist.

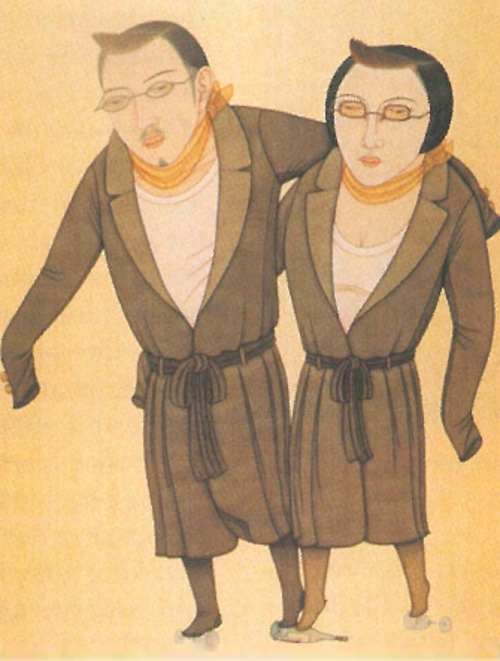

With a kowtow to Homi Bhaba, Gao Minglu concedes a 'third space' to Chinese artists working overseas, who have learned to present "traditional materials as ... bridges over which different interpretations can cross." They are the "post-Orientalist transnationals."

Yet hybridity of this kind is neither new nor surprising. In Modern Asian Art (1998) John Clark places it in perspective with a series of diachronic case-studies of artistic modernism in Asia. Clark warns against the " acceptance of a type of transfer of cultural capital " from Asia to Euramerica almost on the terms that now govern economic exchange." He notes that "it was just when some Asian art discourses had begun to lose interest in any further reference to a Euramerican stylistic that Euramerica began to think of Asia as a typical example of the PostModern."

This may be managed deception, he hints, noting in relation to contemporary Chinese artists that 'Chinese' culture is sometimes highly oblivious to the politics of self and 'Other'-naming. Which is to say, the move into a 'third space' as a way of negotiating global cultural politics may merely be another means of storming the headquarters.