In 1979 Rover Thomas was known throughout the Aboriginal world of the Kimberley. Not, as it may be thought, for his fame as an artist but rather as the vehicle, the Dreamer, of the Kurirr-Kurirr ceremony.[1] This dance cycle or palga focussed on a spectral odyssey undertaken by the spirit of Rover's classificatory mother.

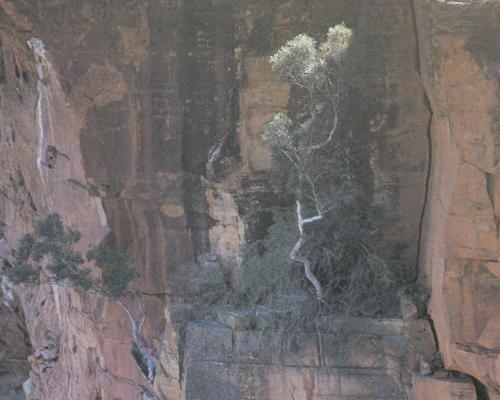

Killed in a motor vehicle accident in late 1974 she appeared, in 1975, to Rover in a series of dreams. In these dreams she transmitted to him the songs and images required to present the narrative of her journey as a shade across the Kimberley landscape. Rover was to develop the verses and teach them to others; as well as instructing and supervising the creation of a series of painted boards. Each board related to an element of the cycle and they were revealed sequentially, carried by dancers accompanied by songmen and a chorus chanting the appropriate verse. The cycle itself told of her spirit journey undertaken in the company of several other spirit beings across much of the eastern and central Kimberley. One dramatic passage refers to the spirits stopping and, from Kelly's Knob in Kununurra, looking far to the northeast to see Cyclone Tracy (itself a manifestation of the rainbow serpent), destroying the city of Darwin.

Initially, the cycle did not generate much public interest. By 1979, after Rover laboured, reworking the entire sequence, the Kurirr-Kurirr was enthusiastically received by the entire Warmun Community. This palga was to become a cultural icon for the Miriwung and Kija people of Turkey Creek.

The dramatic artworks, integral to the success of the palga, were originally executed by a number of artists, the most noted being Paddy Jaminji. While directing the imagery to be used on the boards, Rover himself did not commence painting until 1982.

Promoted by Perth gallery manager Mary Macha, Rover's work became rapidly sought after by discerning collectors. Strangely, a number of public galleries did not, in the mid-1980s, find that his work or indeed that of any of the Warmun artists merited inclusion in their collections.

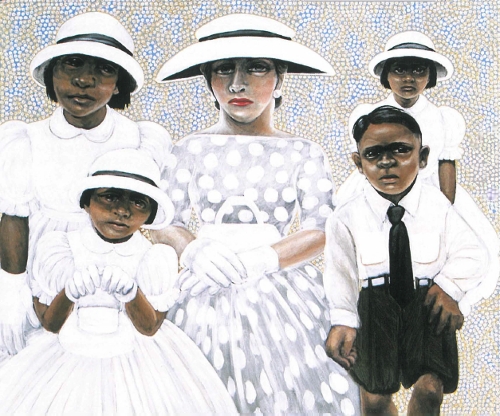

By the 1990s however, works by Jaminji, Rover, and many of the other highly competent artists of the Turkey Creek or Warmun School of painting as the movement came to be called, were eminently desirable additions to any collection. The interest in this art led to a dramatic rise in the number of commercially oriented outlets and entrepreneurs focussing on Warmun and other east Kimberley centres. A regional explosion of production and marketing ultimately resulted in an unparalleled output of works in a variety of media.

Rover himself was born deep in the Great Sandy Desert of Western Australia in about 1926. Leaving the desert in his youth he was thrust into the world of the Kimberley stock camps and worked on a number of cattle stations. Stock work and other station-related activities took him to many parts of the Kimberley and the adjacent Northern Territory. In 1975 he became a permanent member of the Warmun Community, resident at Turkey Creek in the east Kimberley.

Rover's richly textured life is reflected in the Kurirr-Kurirr, in the verses that take one across the Kimberley landscape with its deep cosmological associations, and in the art inspired by the spiritual revelations of the narrative. The vehicle of the dream-imparted odyssey permitted him referential access to sites and countries normally the prerogative of traditional owners and their affiliates.

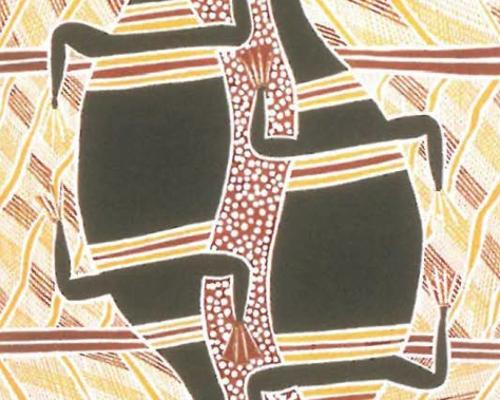

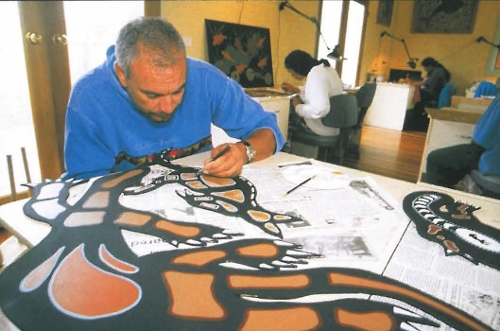

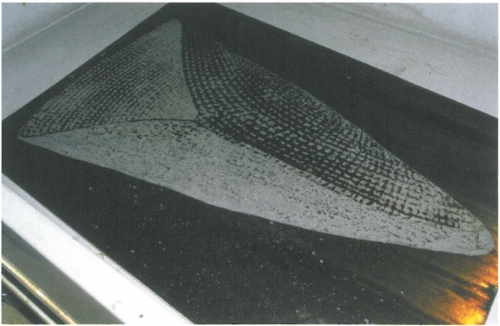

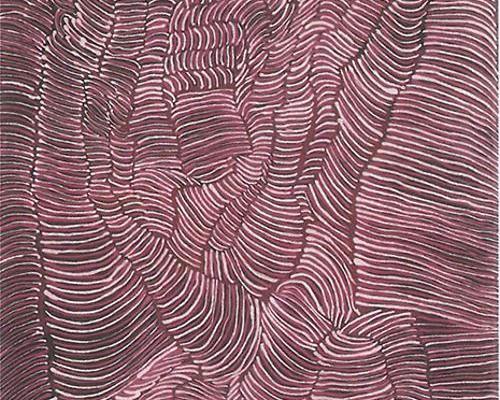

The art of the Kurirr-Kurirr can be seen to have developed directly from the traditional genre of the east Kimberley rock art. Here boldly painted, bichrome figures of humans, animals, objects and spirit beings are usually blocked in with solid red, black or yellow pigment and details and outlines are emphasised with lines of white pipe-clay stippling.

Rover's presentation of sites and landscapes in this genre was a radical innovative move and one in which, at one stroke he not only redefined the conceptual framework by which Aboriginal art is to be considered, but also created an entirely original mode of depicting the land. This form of landscape painting became the basis, with various individual innovations, of the style now recognised as the Turkey Creek or Warmun School of Australian art.

Later works by Rover referred to the murderous clashes that occurred as Aboriginal lands were absorbed by the expanding pastoral industry in the first half of the 20th Century, as well as to landscapes unrelated to those depicted in the Kurirr-Kurirr. In 1995 he made a return visit to the country of his birth at Kunawarriji, Well 33 on the Canning Stock Route. This trip resulted in a series of works exhibited in Melbourne in 1996. After this last exhibition, Rover painted only sporadically and usually only at the instigation of other people. Illness and failing sight took their toll although his ready wit and enjoyment of company never faltered.

If there is another element that gave strength to the original freshness of the early works of Rover and others that emanated from Warmun and the east Kimberley, it must be the textural qualities derived from their creation within a camp environment.

The use of thick layers of traditional pigments affixed with natural resin binders was but a base upon which other events occurring at the moment of painting were forensically embedded. Dust, dog hair, sugar or fats, derived from pannikins and meat tins used to hold water or in which ochres were mixed, all left their traces on these early works. Further charm and strength is to be found in the fortuitous changes of hue that occurred with the use of natural pigments. With the increased involvement of dealers and galleries in the promotion of the art, artists often created their later works in sterile urban surroundings. This, coupled with the increasing use of uniformly hued commercial paints, meant that the rich textural qualities found in the earlier works are no longer seen. A loss, I feel, that diminishes many contemporary works notwithstanding their other, often monumental, attributes.

Rover received due recognition as an artist by the mid-1980s. Annually, from 1987 until his death in 1998, he had been represented in group exhibitions throughout Australia. In 1990 he received the Patrick McCaughey Prize and was one of the first two Aboriginal artists representing Australia at the 44th Biennale di Venizia. In 1994, The National Gallery of Australia held the solo exhibition Roads Cross. This exhibition located him and his work within the cultural and historical framework of the Kimberley.

Rover died on Easter Sunday, 11th of April 1998. As an artist he took the experiences of a rich and varied life and, drawing on the cosmological and historical references that so vividly underpin the lives of Aboriginal peoples throughout Australia, presented us all with a new and profound view of the land we occupy.

Footnotes

- ^ Kurirr Kurirr ceremony has also been known as the Krill krill cermony