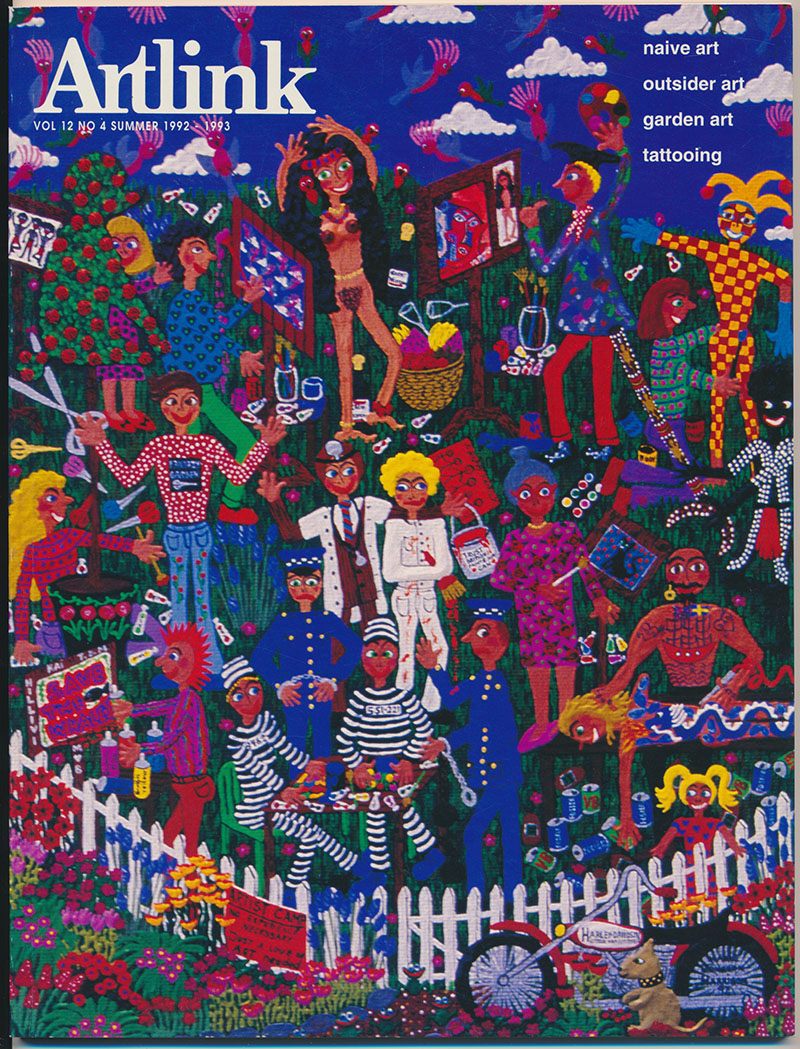

The work by Marie Jonsson-Harrison was commissioned by Artlink, originally courtesy of Greenaway Art Gallery

In 1992–93 Artlink published Naïve & Outsider Art centring on themes linked by their shared invisibility in mainstream discussions. While the title obviously references art historian Roger Cardinal’s 1972 book Outsider Art, (after Jean Dubuffet’s ‘Art Brut’ or ‘raw art’), this outlying status was described by Artlink’s founding editor Stephanie Britton in 2022 as ‘…the context changes, but at the time the concept [of various practices lying beyond the mainstream] functioned as a catch up on things that had been under the radar for decades already... [we were] collating a wide range of ideas'[1], a group of practices that existed but were hardly recognised in published texts. Looking back across Artlink’s history, Naïve & Outsider Art offers much to think through about the magazine’s own platform, intentions and the trajectories of those practices foregrounded thirty years ago under what are now troubling rubrics.

Incipient and backtracked—but cogent and alive—ideas, especially those sidelined by the academy, have always been central to Artlink. Yet if some animals are more equal than other animals, likewise some art practices have turned out to be more robust in public intellectual life than others. For example, Indigenous resistance, sovereignty and agency, or advocacy for a vulnerable global ecology that Artlink consistently centred from the late 1980s onward, often before they registered with the slower moving institutional cultural leaders, are now foundational to cultural life in Australia. However, the resonance and continuity of the practices discussed in Naïve & Outsider Art has been less clearcut.

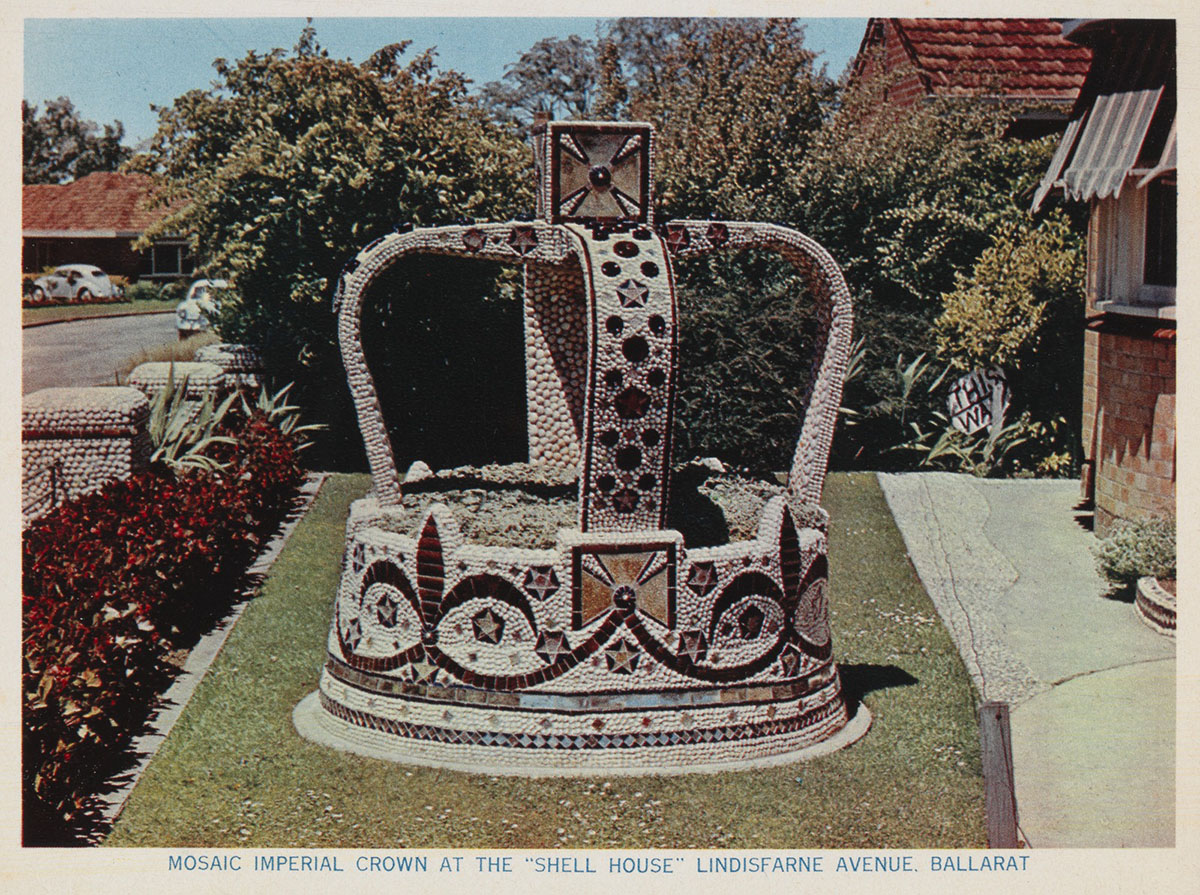

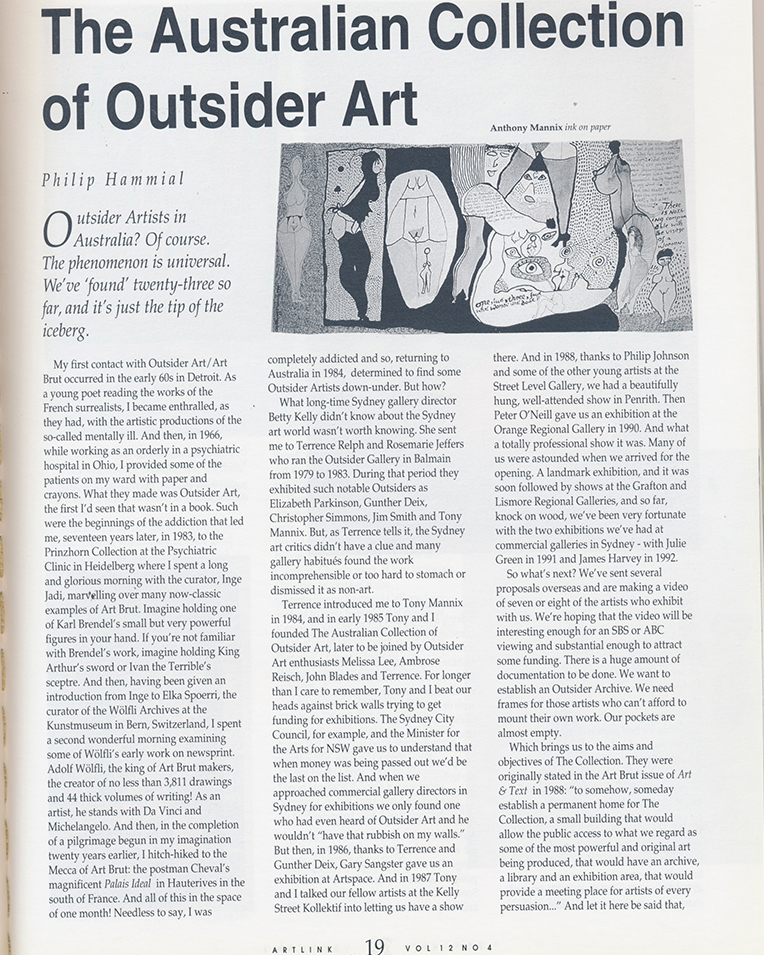

Looking back with a revisionist model typically invokes taboos and shibboleths that have shaped Australian contemporary art practice and discourse, yet few dare to probe or question them. Discussion around Naïve & Outsider Art as it occurred in shaping SENSORIA: Access & Agency in 2022 involved a degree of disbelief and defensiveness. Clearly, contemporary readers may not feel entirely comfortable with some of the language and ideas endorsed in Naïve & Outsider Art, given the ‘othering’ that ‘outsider’ has come to imply. There was also bafflement at the random nature of the content and the editorial irregularity that endorsed such disjunctive line-ups, and the implied judgement of the combination: the (sadly) now-perceived bizarreness of suburban garden sculptures, tattoo art and a range of artists working in an 'outsider' style. Prominently featured were artists with disabilities and mental health issues along with the organisations that engaged with their art, such as the Cunningham Dax Collection, Arts Project Australia, the Australian Collection of Outsider Art, and naïve artists more generally, who in 1992–93 had some market and critical support. For instance, Daniel Thomas opened Iris Frame's exhibition curated by David Hansen at the Riddoch Gallery in Mt Gambier.[2] Renowned artists such as Anthony Mannix and H.J (Harry) Wedge were also featured, with blurred boundaries and ambiguities over nomenclature, which practices were legitimate or ‘authentic’ and which less worthy. David Hansen wrote of ‘faux naïve artists’ and it would seem most of the white rural working class, autodidact creatives included in Naïve & Outsider Art because their practices had intrigued more mainstream artists and art writers, represent a tranche of artmaking that has become less visible.

Questions are raised not only in hindsight: at the time, not all those who appeared in the magazine were entirely happy with Naïve & Outsider Art’s groupings. Some within the tattoo subculture were angry at being classed with the naff-ness of eccentric pensioners and their wood carvings, pointillist houses, gardens of shells, broken china and concrete obelisks. Equally, they resented the implied pathology of association with art therapy and art practices affiliated with mental health institutions and the ‘unwell’. They saw themselves as more transgressive, avant-garde and intentional than the ‘naïves’ and more alert and in control than people with any type of disability or medical disorder: in short, authentic creatives with their own agency. Was this bohemianism? Or common garden ableism? Perhaps Naïve & Outsider Art’s ‘learning moment’, akin to a memento mori, is that however righteous the cause, however deep the inequality that wounds and hinders—and tags and brands with slurs, diagnoses and value judgements—we are all subjects of, and victims to, the shifting moments and the mutability of generational values.

A lingering hostility towards the ‘everyday’ also assumes that ranking different practices is cogent, not only as part of the legitimate duty sheet of art professionalism, but also as a way of artists framing their own practices: artists feel erased or diminished when placed in alignment with practices lacking status or validity, or which represent a perceived political or cultural misstep best kept at a distance. This process has not changed significantly: reputation building and keeping in the right company is all part of a professional, critically positioned and well marketed art career. Artists today may choose their curatorial categories with often quite strategic intent. In this context the ‘curios’ of suburban garden sculptures or the hyper-upbeat buoyancy of naïve art suggests a subset of contemporary art making that has substantially lost prestige and profile in Australia since the 1990s,[3] whereas there has been significant efforts to realign—and increasing awareness of— how we think of artists with a disability, mental health issues or chronic conditions.

However, in Naïve & Outsider Art all the practices were seen as allied, (despite differences), in being undervalued by the mainstream art world. Activism and personal truth presuppose a Darwinian assumption that a position is achieved through a struggle of potential rival aspirants and competing self-interests. Distinction and recognition is fought for, and attained, against those forces—reinforced by gatekeepers—which deny access to those seen as less deserving, or those who seek to keep opportunities centred on the powerful and enabled.

Compassion for whom?

Three decades on, art commentaries witness a greater suspicion about confessional, performative emotions, catharsis and self-identification of ‘difference’, often laid on the round table of the Artlink editorial process. As guest editor Alisdair Foster claimed in The art of Compassion issue (2020), Blur Projects ‘documentation of “the kind of injustices arising at the intersection of multifactorial issues of social inequity” emphasises the necessity of ‘defend[ing] against the vanity of seeking to be known as compassionate, but also in avoiding in the audience the kind of emotional catharsis that lets the viewer feel good about themselves without any real transformation of their perspective’.[4] The assumption that all gestures and intentions, no matter how well meant, are malign and intended to trigger harm has become a baseline in much cultural commentary. When does authentic concern and personal truth become cliché? Does vernacular, ‘outsider’ creativity tap into those sidelined tensions between class, visibility, ableism and cultural leadership?

The progression of what was termed outsider or more recently and positively ‘outlier’ art as curator Lynne Cooke proposed in 2018 [5] —now sees artists fearlessly mapping their own space and agency, without concession to perceived adversaries. Artlink documents this change directly, as demonstrated by the artists’ profiles collected by Blur Projects: ‘My name is Jason. I’m 17 and I’m non‑binary. I have fibromyalgia, chronic pain, autism, ADHD … Able‑bodied people, straight people, cis‑gendered people, need to stop and realise that sometimes they don’t have all the answers, and sometimes they need to listen to the answers of others.’[6] Numerous online platforms and journals such as Bramble for and by Australian creatives with a disability, funded by the Australia Council open up space where practitioners themselves can shape context and commentaries. When assembling SENSORIA: Access & Agency, the power of words, names and implications of framing was the subject of weeks of streamed and emailed discussions. Self-identifying is becoming central to understanding cultural practice and creative projects. Not being spoken for and over, the need to affirm a personal position and, at the same time, not to obtrude on the space/positioning of others marks a distinctive generational change.

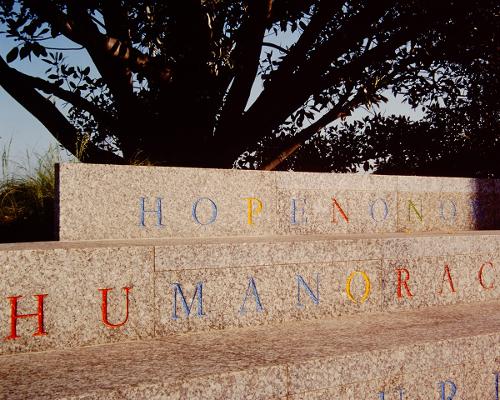

For all its noise, such as the toppling of confederate monuments, much activist art does not fully engage with the multiple complexities of simply surviving, let alone creating memorable art. Could one say that the true calibration of the context of how well the creative scorecard around outlying and marginal artists is faring may be found in the multiple cut backs to the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) packages being contested in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal in early 2022?[7] NDIS is an invisible player in arts funding, given many artists and creatives rely upon NDIS for survival, just as Jobseeker, call centre, cleaning and hospitality work have long provided de facto and unacknowledged minimum wages for artists. Another indication of the situation facing outlying artists is the ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome) advocacy group Emerge, whose lobbying activities push for changes to outdated diagnostic and treatment criteria still listed as best practice for Australian doctors in managing chronic and autoimmune conditions.[8] The list is long, with some conditions attracting a tangibly higher level of official scepticism from medical professionals. Beyond that, the pandemic and long Covid have triggered a Tsunami of autoimmune conditions, often convenient to ignore and brush aside at an official level, adding to the ‘invisible’ health crisis of complex, elusive disabilities.[9] When Jill Bennett wrote in her editorial for Artlink’s Anxiety and Mental Health issue in 2017, [that] ‘we live in ever more anxious times—a post 9/11 climate of fear and xenophobia, personified by Donald Trump and compounded by economic uncertainty’[10] little did she know that in 2017 three years ahead of the pandemic, we were only standing on anxiety's front porch.

Advocates and institutions in 1992–93: where did they land?

As with animals, some institutions are more equal than others. Founded in 1974, Arts Project Australia remains notable for its tenacity and longevity and its main platform of working within, rather than contrary to, the values and the institutions of mainstream artmaking, offering much exposure for its artists. As Chris McAuliffe wrote in 1992, ‘Arts Project likes to participate in arts structures rather than shun them’.[11]Arts Project Australia has enjoyed a relatively robust level of stability and private charitable support, beyond that of many independent arts organisations, such as dedicated buildings and regular charity fundraising auctions. This stability has played out in a consistently high profile and standard of public presentation for the organisation. As documented by CEO Sim Luttin in SENSORIA, its reach has expanded to participation in global events with parallel organisations in other countries, and a range of supported studio models exist across the country.

The Australian Collection of Outsider Art, founded in 1986, has remained in private hands, split between longstanding supporters of the archive and its vision, artist Anthony Mannix, and poet Gareth Jenkins. Its goal, as stated in Naïve & Outsider Art for its own gallery, archive, library and ‘a meeting place for artists of all persuasions’[12] has not become reality. As Philip Hammial stated, the collection was struggling to attract official notice ‘when money was being passed out we would be last on the list’,[13] but it also has enjoyed fruitful cooperation with institutional supporters and fellow travellers, such as the late Alan Sisley and the now expatriate Colin Rhodes. As director of the Orange Regional Gallery, Sisley offered a consistent and esteemed locus of support and display opportunities for neurodivergent artists more than two decades ago.

‘Curative histories’

Another organisation featured in Naïve & Outsider Art that also survives is the remarkable and globally important Cunningham Dax Collection.[14] Now rebranded The Dax Centre, its meandering narrative suggests that a taboo still hovers around it, despite the unparalleled historical and aesthetic significance of its content. Located at Parkville, at the University of Melbourne site since 2011, it emphasises the informational and educative function of the collection as a means of brokering sympathetic understandings of mental illness and wellness rather than celebrating the powerful aesthetic of its works, much of which is exhibited and reproduced as anonymous. As with early collections of Indigenous art, attribution was an afterthought, the collated ad-hoc as patients were not granted the agency of artists.

This shadow hovers around the collection: the therapeutic diagnostic harvesting of the art of the mentally ill, from the 1900s onward (and from the 1950s under Dax’s watch) has all the problematics of abuse and lack of civil and human rights—let alone misdiagnoses and prejudices— endemic to the history of the medical treatment of mental health in central Europe and beyond. Dax came to Australia as a reformer to the mental health sector but could not escape this backstory. When writing on a selection of women's work from the Cunningham Dax Collection in 2007, I noted that there is no way to second guess what the artists thought of the removal of their work by a senior medical professional who was servicing their ‘cure’ and calibrating that cure by their behaviour and compliance. An unambiguous ‘NO’ in large letters appears in a work by an unnamed woman from the 1950s.[15] The many iterations of the Dax Centre's webpages from the 1990s onwards captured by the US Wayback Machine and the National Library of Australia's Pandora Archive shows how the collection is working to remedy this element of its history as social and professional norms changed over the past three decades.[16] The history of past health practices is complex to resolve and resonates globally and cross-culturally far beyond the collection in Parkville.

Like the British Museum collecting global non-Western contemporary art in an early if simplistic form of apology for its historically contentiously non-consensual acquisition,[17] the Cunningham Dax collection has since used its status to provide space for practices to which it once acted in a seigneurial manner. Anyone who made an artwork that related to experiences of mental health or illness, including carers or family members, could donate work, an access more recently extended to trauma-related experiences. In 2011, the collection briefly segued to a more formal curatorial and arts management model, drawing gallery staff from arts professionals and academics, only later to be apparently divested from direct curatorial alignment to the art theory and arts management sectors. Now partnered with SANE Australia, the professionals on its Board are drawn from the medical, not the art sector. Is it too much to suggest that the Cunningham Dax Collection sits outside a border around acceptable curatorial practices and values that the likes of Arts Project Australia uphold? Although for many years its admittedly devoted stewardship by Dr Cunningham Dax put the collection in a fraught position to mainstream curating and art management, he always emphasised the medical and therapeutic function of the artworks. In 1992 Traudi Allen directly engaged with Dax in an ABC radio documentary and later interrogated his position in her article for Naïve & Outsider Art.[18]

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne Gift of Erica McGilchrist 1999 © Estate of Erica McGilchrist

Further to the histories in this essay, this work and others painted by Erica McGilchrist in the 1950s stands out against the ableism that constitutes much public and known art historical narratives in Australia. It emerged from the artist's art teaching work at Kew Mental Hospital for Dr Cunningham Dax in 1953-54 (he also opened her solo exhibition in 1954). While Dax expected her to provide materials and demonstrate their uses in a neutral fashion, McGilchrist engaged in more complex interactions with her students, unofficially offering advice and assistance as needed on themes, design and materials, and her favoured medium of expensive multi-coloured pencils is frequently encountered in the earlier holdings of the Dax Collection. Her paintings were unique in Australian art in an era when mental illness was a social stigma, and she herself recalled that people of Melbourne packed sandwiches and drove to Kew to gawk at the patients in the airing court as Sunday afternoon entertainment. Her works also presciently posit a social rather than a medical basis for mental illness, making comment upon hate, the holocaust, social alienation, the oppression and sidelining of women in post-war Australia. She recalled questioning whether the ‘insane’ were outside rather than inside the hospital. Feeling trapped in her prescribed role as a woman in the 1950s and even in her marriage, she found the situation of women imprisoned ‘in a Kafka-like situation from which there was no escape’ resonated with her own condition. She was deeply interested in psychology and psychiatry as theories in the 1950s and read widely on these topics, and drew a series of abstracts in ink, “Moods", which depicted various states of mind and clinical diagnoses of the time. Her contemporaries sniggered offensively, ‘she’d taught art to the loonies and was now doing her best to paint like them.

Another showcase of alternative creativities in Artlink was the debut of STOARC, the Self Taught and Outsider Art Research Collection in the 2009 Rational/Emotional issue.[19] Like the magazine, (Artlink is currently housed at Glenside Cultural Precinct in the former Glenside [Mental] Hospital), STOARC was based in the former Sydney's Callan Park Hospital for the Insane (1878–1914) at the University of Sydney / Sydney College of the Arts (SCA) then Rozelle campus. STOARC promised to put Australia at the forefront of global engagement with outsider art, offering a dedicated public gallery, a rapidly expanding collection, and a peer reviewed international journal devoted to outsider art as well as an outsider arts research cluster at the University of Sydney. It formed partnerships with longstanding stakeholders including the Australian Collection of Outsider Art and Arts Project Australia. Collectors and gallerists such as Peter Fay, Stuart Purves and Ray Hughes, who had established interests in and advocacy for non-standard practices also lent support or donated works. Yet STOARC disappeared in 2016 after seven years of important work, collateral damage in the controversies surrounding the proposed amalgamation of SCA with UNSW’s College of Fine Art (COFA), the resignation of the Dean Colin Rhodes (a driving force behind STOARC) and the move of SCA from its remarkable historical site at Rozelle. This complex and fraught story of art and academic politics including student protests, occupations of buildings and high profiled staff resignations, as well as intense and fully justified battles to defend tertiary art education in Sydney, overwrites the closure of a major centre of focus on alternative creativities in Australia and overseas and the disappearance of a collection of Australian and international artworks, apparently donated to the Museum of Everything in the UK, self-described as a ‘wandering institution for the untrained, unintentional, undiscovered and unclassifiable artists’.[20]

STOARC's vernichtung certainly reduced the public facing energy and profile of outsider art in Australia, with neither the Australian Collection of Outsider Art nor the Cunningham Dax Collection ever enjoying such centrality. The vaporisation of Australian corporate collections built up since the 1950s yet auctioned off frequently in the post–2000 period, is a familiar event in the secondary market for Australian art, with the NAB and CBUS collections coming to the auction block in 2022. Corporate art collections seem to be the equivalent of keeping the cheese station well stocked at the expense of maximal capitalist flexibility in Australian neoliberal practice. Could we have hoped for a greater degree of permanency and responsibility to artists, artworks and audience from a public collection like STOARC? Put another way, can we imagine a public institution, devoted to either women’s art or Indigenous art, being permitted to be exported without protest? Can we accept important collections of contemporary art remaining outside mainstream public institutional support as a private archive, as the Australian Collection of Outsider Art does?

The establishment of STOARC in 2009 and the University of Melbourne’s claim for global leadership with its 2014 conference Contemporary Outsider Art: the Global Perspective, and a major exhibition, made outsider art look momentarily like the new black.[21] Overseas, the appreciation has remained more robust as an identifiable subsector of both art collecting and dealing. New York’s Outsider Art Fair heralded in Naïve & Outsider Art as a start-up initiative that boded well for the consolidation of the sector is still in operation, now in Paris too. Without a dedicated exhibition space, the Museum of Everything has curated temporary exhibitions from its collection in association with major arts festivals and venues around the world. Outsider art has appeared at the Venice Biennale in 2013 and 2017, and documenta in 2022. Australian writers with a global perspective on outsider art have noted that the sector has lost public traction, prestige and profile in Australia since the 1990s.

Today [2015-2018] however self-taught art has a very low profile in Australia. There are no commercial galleries specialising in the field and very few dealers represent artists of this kind. Although many art school graduates have appropriated the tropes of outsider and self-taught art the actual creators of this type of art are ignored by our major institutions. With the notable exception of Arts Project Australia, they travel under the radar. [22]

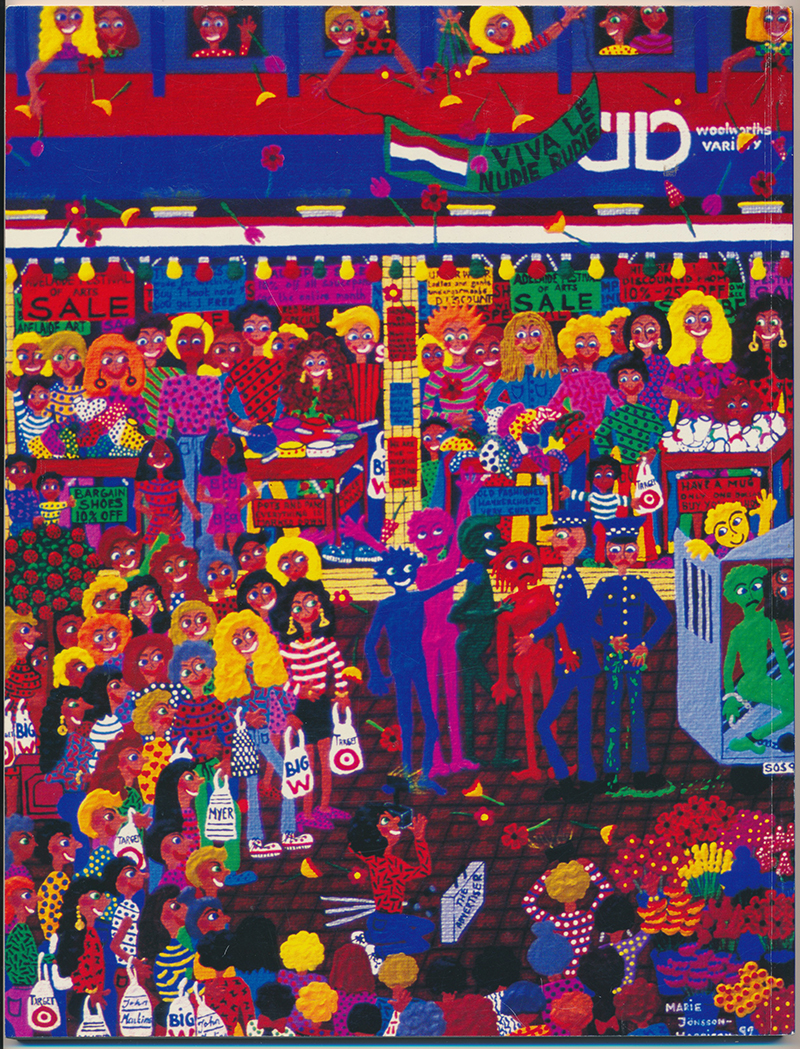

The loss is most noticeable in self-styled naïve art which flourished through the 1960s –1990s. Artlink commissioned Adelaide naïve, Marie Jonsson-Harrison for the 1992–93 cover as a collective portrait of the outsider art scene in Australia; the back cover documented South Australian police arresting naked performance artists in the Rundle Mall during the Adelaide Festival. Now ‘naïve art’ is mostly celebrated in the work of some Indigenous artists although the adjective has been problematised along with other contentious terms including primitive and tribal. Naïve art was a burgeoning field and safe haven for figurative content against the professional domination of both masculine abstraction and conceptual art until challenged by second wave feminism in the 1970s and post modernism in the 1980s. A wide variety of artists who had considerable degrees of training in and awareness of art and design paradigms were co-opted as naïve in the 1970s, from Greg Irvine to Mirka Mora. The latter's reputation in the 1970s was more as an adjunct to mainstream artmaking, with her huge popular following and widespread press coverage, but was not accepted by the post-object and conceptual art champions of Mora’s day. The first monograph on Mora’s work was published in 1980 by Australian-based advocate for outsider and naive art, Ulli Beier.[23] Art historically and curatorially, Mora is now closely linked to Heide and the Angry Penguins, also the urban migrant post-war diaspora placing the artist into an exponentially more formalised cultural and intellectual context than she was assigned four decades earlier. Beier collected, documented and promoted outsider, transcultural and contemporary art and literature from many cultures, including Australia, driven by a syncretic and globalising personal vision.[24] He spent his later years in Sydney where he associated with the cluster of makers and advocates for outsider art in that city, publishing Outsider Art in Australia (with Phillip Hammial) in 1989.

With feminism, post modernism, neo-expressionism and photography and video offering a greater legitimacy to various forms of figuration from the 1980s onward, the ‘camouflage’ of naïve art became less necessary as a means of validating legible, but not necessarily mimetic, pictorial motifs. The trajectory of divergent art practices in Australia invokes the transgenerational pattern of a particular idee fixe dominating both critical and curatorial narratives at a given time, and the strongly collusive and self-reflexive tendencies of the centre of the Australian professional artworld.

Artlink's Kitsch and Bad Taste (1995) revisited vernacular creativity and popular culture mediated through irony, camp, queer culture and even nascent post colonialism, as well as a refusal to denigrate the domestic and the feminine. Although a hint of the traditional Art Brut celebration of ‘unfettered’ ‘impolite’ and ‘raw’ creativity against mainstream norms still lingered. The 'under-esteemed art' concept later segued into a normalised celebration of established art world figures in Artlink’s Elders: the Old Magic (2006). In 2014 Graffiti: Wall to Wall explored vernacular creativities conjugated through the prophylactics of class, race and rebellion against forces of urban order and capital. The issue had synergies in its subcultural expressive urbanism and self-determination to the tattoo artists and advocates who felt misrepresented in Naïve & Outsider Art.

The complexities of power structures involved in advocating for non-mainstream or ‘recentred’ art have already brought a bad fairy's christening gift to the sector. Interrogating this irony of art experts desiring wild freedom, whilst simultaneously claiming the privileges of senior rank and authority was part of the densely packed basket of iconoclastic art theory that Donald Brook regularly left at Artlink's doorstep, another major story in itself for another time and place but one that links with the publication's endorsements beyond the central and commonplace. The use and exploitation of the ‘other’, and central/marginal power structures sometimes compromises advocates of divergent art practices and their gestures of homage and promotion. Conversely, the Australian Collection of Outsider Art has survived for nearly four decades in sympathetic custodianship.

The work by Marie Jonsson-Harrison showing French performance artists being arrested at the Adelaide Festival.

As Sylvia Kleinert noted in Naïve & Outsider Art, the origins of Dubuffet's advocacy for Art Brut and outsider art both mirror and appropriate. Dubuffet simultaneously celebrates and exploits marginal figures who privilege ‘the very style of art he desires to produce himself.’[25] Likewise, Ulli Beier racially impersonated African and New Guinean writers when publishing his own creative works, it ‘is especially hard to deny egotistical involvement on Beier’s part, as Beier centres himself in his displacements,’[26] not withstanding his broad contributions to the field of intercultural arts practice. Long after Dubuffet championed Art Brut, there are numerous examples if one looks through a certain lens, in which appropriations of creativities, and the search for redemption via the consumption of the pure, still have traction. Chris McAuliffe’s 2014 paper at the University of Melbourne's 2014 conference supports these ideas and indicates how the mainstream unashamedly locates a use-value in the simultaneous alignment with, and rescue of, outsider art.

Outsider art, which already takes its dreams, or nightmares, for reality embodies that imagination. Escaping both spectacular novelty and melancholic lassitude, it is exhibited alongside mainstream contemporary art as an ecstatic affirmation of art’s capacity to be beyond. Outsider art offers the utopian figure of the not-yet; an updated version of Ernst Bloch’s philosophy of hope, which posited that Utopia rested latent within history as a tangible potentiality not yet realised.[27]

The use-value of outlying art is not just wistful thinking, or romantic self-identification, it has a baseline practicality. In the intense pressure to carve out subjects for competitive research grants and direct large government grants towards art and art history teams, within the often cash-strapped humanities sector, in recent years non-standard practices have been the subject of successful research applications such as the ARC Grant Recentring Australian Art: Beyond the Fixed Canons of Australian Art History with a team from Melbourne, Monash and RMIT Universities (2018) and Constructing the first Australian archive of disability arts with academics from Queensland University of Technology, Curtin University, the University of Melbourne, Arts Access Society Inc and the Australia Council (2020). Yet when creatives gain success and a public platform due to their demonstrable, performed competence, it begs the question what standards are applied for those neurodivergent and/or neuroqueer individuals navigating the constant ‘microaggressions’ of everyday lived experience while maintaining a viable practice. As noted above, mainstream culture and public life in Australia often fails to acknowledge the extent of chronic disabilities, visible and invisible, in our society; it offers few solutions and insufficient support to those living in the subaltern strata. Artlink's archived pages provide possible answers: hence we may return to Jason’s quote that ‘Able‑bodied people, straight people, cis‑gendered people, need to stop and realise that sometimes they don’t have all the answers, and sometimes they need to listen to the answers of others’[28] or as M. Sunflower writes in SENSORIA: Access & Agency, ‘I wasn't going to any exhibition openings. I was barely getting out of bed.’ [29] Or as Kelly Hussey-Smith put it The art of Compassion, ‘In its prevailing form, contemporary art is created by and for individuals, subjectively in keeping with the economic and ideological framework of our times... the art market still relies on a model of celebrity that owes much to the romantic idea of the genius artist.’[30]

Considering the nature of outlying art inevitably throws into relief the assumptions and values of the centre, the able, the mainstream and the dominant. Here is one plausible reason behind the unstable backstories that I have charted, which cause uncomfortable questionings of certainties and implicates the insiders whose remit has been not to question their own authority.

Footnotes

- ^ Stephanie Britton email to the author Juliette Peers 14 June 2022

- ^ Rimas Riauba, “Masterminded masterpieces: legendary art”, Artlink 12:4, (1992–93), 48

- ^ Sylvia and Tony Convey, “Self-taught, outsider + visionary art”, https://www.tellurianresearchpress.com.au/self-taught-art.html

- ^ Alasdair Foster, “Between worlds: Belinda Mason and Blur Projects”, Artlink, 40.3 (2020), 16

- ^ See Lynne Cooke, Douglas Crimp and Darby, English, Outliers and American Vanguard Art (University of Chicago Press: 2018), exhibition catalogue for exhibition of the same title at the National Gallery of Washington curated by Cooke.

- ^ Foster, 17

- ^ Elizabeth Wright, Celina Edmonds and Evan Young, “Government agency accused of being ‘at war with those it should be supporting’ as appeals against NDIS cuts spike”, ABC News, 29 April 2022, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-04-29/government-accused-failing-ndis-participants-amid-funding-cuts/101009408

- ^ See Emerge: https://www.emerge.org.au/clinical-guidelines

- ^ Donna Lu, “‘We never seem to recover’: the Australians grappling with long Covid”, The Guardian, 12 February 2022 https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/feb/12/we-never-seem-to-recover-the-australians-grappling-with-long-covid

- ^ Jill Bennett “Editorial” Artlink, 37:3 (September 2017): 10

- ^ Traudi Allen, “Mental Disturbance and Artistic Production” Artlink 12:4, (Summer 1992–93), 25

- ^ Philip Hammial, “The Australia Collection of Outsider Art”, Artlink 12:4, (Summer, 1992–93),19

- ^ Hammial, 19

- ^ See: https://www.daxcentre.org/collection

- ^ Juliette Peers, “Sometimes Madness is Wisdom”, Sally Northfield ed., Canvassing the emotion: women, creativity and mental health in context: selected works by women, 1950s to now from the Cunningham Dax Collection, (Parkville: Cunningham Dax Collection, 2008), 6

- ^ The history of both arts management structures and philosophies of the Dax Centre can be reconstructed through archived websites covering three decades, which deserve a more detailed analysis than possible here

- ^ See Frances Carey ed., Collecting the 20th Century (London: British Museum Press, 1991)

- ^ Allen, 22-23

- ^ Colin Rhodes, “Inside Sydney's new Outsider art centre”, Artlink, 29:3, (September 2009)

- ^ The Museum of Everything, https://www.musevery.com/#about

- ^ See Fiona Gruber, “Outsider art and why the mainstream always wants a piece of it”, The Guardian, 1 October 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/oct/01/outsider-art-melbourne-mainstream-moment

- ^ Sylvia and Tony Convey, “Self-taught, outsider + visionary art”, https://www.tellurianresearchpress.com.au/self-taught-art.html

- ^ undefined

- ^ undefined

- ^ Sylvia Kleinert, “The Boundary Riders: the art of everyday life”, Artlink 12:4, (Summer 1992–93): 10

- ^ Maebh Long “Of Ulli Beier, Obotunde Ijimere & M. Lovori”, PNG Attitude, 21 March 2022 https://www.pngattitude.com/2022/03/of-ulli-beier-obotunde-ijimere-m-lovori.html

- ^ See https://chrismcauliffe.com.au/outsider-art-and-the-desire-of-contemporary-art-october-2014/

- ^ Foster, “Between worlds”, 17

- ^ M. Sunflower “Exquisite Interplay: Accessible Arts Workshops for Emerging Artists”, Artlink, 42:2 (Wirltuti / Spring 2022): 76

- ^ Kelly Hussey-Smith, “Shahidul Alam: you’re blocking the sun”, Artlink 40.3 (September 2020): 39