I am not sure I feel like talking about art. My mind wanders too easily toward anxiety and sadness, life and death, and connection—a fear of it, a desire for it. A palpable notion of being excluded from the accepted systems used to form a functioning society, locked out of (or into) the checkboxes to tick, too tired to jump over the bars that keep rising. This is not an unusual experience for those who live with varied bodies, divergent minds. Not unusual for anybody in this era, perhaps. So, I think. It dawns on me that I have instinctively created my own methods to cope, modes to make sense of this quotidian life between and around embedded social systems, the institutions.

But we are not here to talk about me, we are here to talk about Ruark Lewis. He creates art—conceptual, relational, durational, abstract—and has done so relentlessly, fearlessly, for decades. At once a writer, musician, performer, visual artist of significant reputation and influence, and having actively conducted a rigorous conceptual art practice since the mid-eighties, I had this (valid, I thought) assumption Lewis would be easy to locate. Well, if not in ACMI, NGV, AGNSW, MCA, NGA, the full forensic identification of the artist, these days, is expected to be accessible and exposed to all. Google it: website, images, videos, filed, shared, viewable, streamable, saveable, shareable, commodified, available. But autobiography is not really part of his repertoire, he’s not easily downloadable. As I play hide and seek with the few Ruark Lewis works I find in that vast digital landscape, I realise I don’t need to start with the image; I’m already in there, within a Lewis artwork, by conversing with him, considering, cajoling for didactic documentation, and by waiting. Time forces me to contemplate his work on a slower speed.

In abstract mode.

In absence mode.

In thought mode.

Such is the power of his subliminal messages.

Philosophical paternosters.

Secret patterns.

Systems.

Good morning! Today I live, tomorrow I prepare to do the same. (Raises cup of coffee to sky, then lips).

RELAYRELAYRELAYRELAYRELAYRELAYRELAYRELAY RELAY.

You may have been in a Ruark Lewis work yourself without even being aware of it. Certainly, if you are a keen observer of emerging artistic talent in Australia you’ve seen his influence and reach as one of our nation’s foremost (enigmatically undefinable) conceptual artists whose generous practice owes much to language, deep thinking, and dialogue. An intellect alive with multifarious pathways, Lewis’ research-based life is fuelled by poetry, literature, music, sciences, histories, social justice, creative collaborations, exemplary of an ongoing openness to learning, a polymath—a polymathartist.

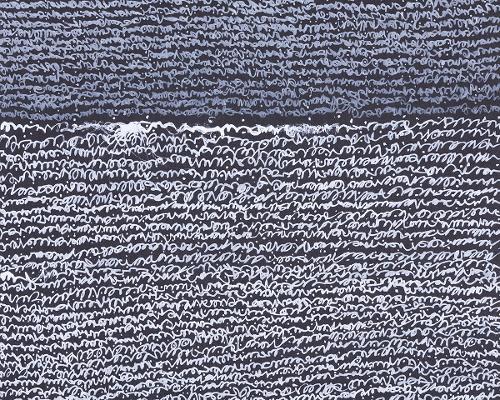

Those of you old enough may have attended the Sydney Olympics, or visited its legacy public outdoor gallery, climbed Lewis’ work at Olympic Park: RELAY, a collaboration with artist/poet Paul Carter. A poem, three kilometres in length, is carved into the front plane of granite stone steps, (difficult to find a more literal concrete poem than that), authentically claimable as a public art piece, created as it was for the global gathering of the 2000 Summer Olympic Games, remaining there to this day now recognised as the Sydney Olympic Park Urban Art Collection—an outdoor gallery, a civic space. The poem (a prose piece by Carter) reflects on four points in Olympic history (colour code systems by Lewis): the Olympic Games at Athens in 1896 (red tier); Melbourne in 1956 (yellow tier); Sydney in 2000 (blue tier); and a future Games (green tier).[1] It is a continuous script, space and colour are utilised for allegory provoking multifarious readings, the first and last letters of each word meet as if to hand the baton over, a relay of words, codified for subliminal transmission.

Through the process of conversation with the artist further insights are revealed. Secrets now to share. The carved font, based on Garamond, adapted by Lewis—Sydney Olympic Garamond font. Each letter has design alterations, for as the artist recognises, when a letter is enlarged from a symbol on a page to a 30cm-high-carved-in-stone-intaglio sculpture, it suggests possibility and responsibility for further meaning. ‘It becomes more physical at that scale, a character requiring more detail. Making muscles for the letters, a dancer, a micro-detail interface for the audience suggesting a more athletic appearance… subliminally.’[2] Each letter has its own unique physical form, characteristic of a dancer (a nod to Russian-born French artist-designer Erté), requiring meticulous precision, the files sent to the stonemasons were blueprints with no room for corruptions. Despite an openness to reception and translation, to create possibility of mystery, the intent is exact.

This commission, an extraordinary feat of conception, design and build, requires a grand team, including the artists, architects Hargreaves Associates, fabrication experts, skilled craftspeople, labour. I think of the practicalities of such a project, the physical and intellectual demands. I imagine the artist 22 years ago, moving with walking aids, managing the limitations of his body against the ambitions of his precise creative vision. The artist, project manager, team member, went daily to site for the duration of the build—five months or more. Remembering that time, the toll it took on him physically, leaving him exhausted and unwell, he admits ‘I couldn’t do it now’.

CONVERSATIONS. TRANSLATIONS. BANALATIES.

The methodology of nomenclature which assists to categorise and record variant iterations while acknowledging their connective concepts becomes evident in the titles of Lewis’ pieces/actions. These titles—categories/series/thoughtlines/poems—can encompass variations of linked performances, texts, paintings, projects that morph over time, years, involving iterations that can be as elusive as the artist himself.

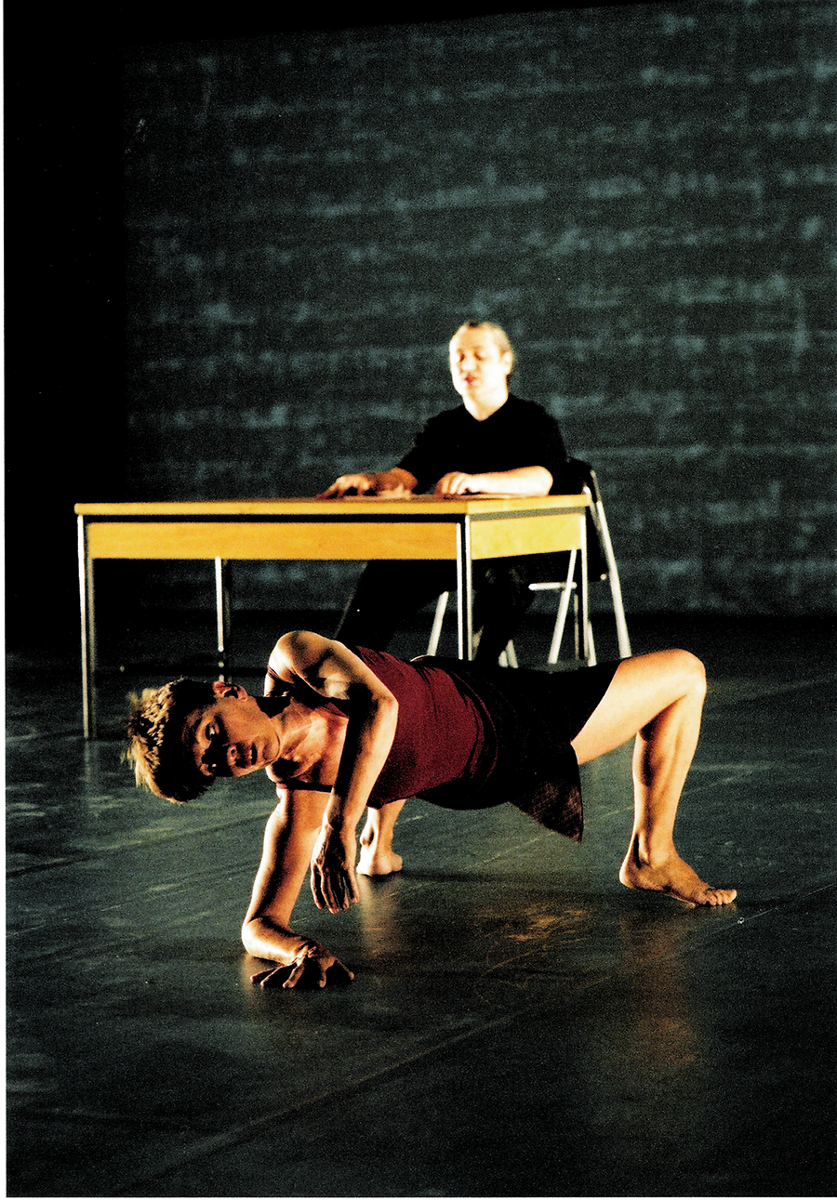

Banalities: Banalitäten, a 25-minute performance piece (unrecorded and unseen by me) commissioned by the LiteratureWERKstatt for the Berlin Poetry Festival in 2003—a highly experimental interdisciplinary literary event—provides fertile creative ground for Lewis (conceptual artists, paid and supported!). Lewis co-designed the set, converging writing, projected text, dance, audio, performance. Collaboration and translation were key with creative partners Rubato, internationally acclaimed experimental German dancers/choreographers Jutta Hell and Dieter Baumann. In this performance Lewis is centred, his body, movement, voice. Utilising spoken word poetry, a unique method of glossolalia, the artist unnerves. Twelve different motifs with text were uttered, music and lighting changed through ten zoned compartments of the performance. Hell’s ‘dance’ is a shadowing of Lewis’s movements, unique as they are, and his theatrical drama of disturbing speech. This translation exchange, physical and sonic, succinctly combines signature elements of Lewis’ ongoing experimental strategies for creating pieces. What it all means? A nonsense question, even Lewis can be perplexed by what is created, perhaps Hell symbolises the internal artist, the psyche, that terrible fear of the artist becoming lost to insanity, the terrifying Unrealised Projects.[3]

Banalities has been the name I’ve applied to numerous post-poetry writing projects. The structure of the writing comes from stacking and sequencing a kind of chance generated writing. The lines are generated by a structured procedure. I want the sentiments uttered to be formed by generalisations.[4]

There are numerous iterations of Banalaties, as James Paull observes in the survey publication Thoughtlines:

Banalities has become for Lewis a way of life. Invariably termed ‘index’, ‘banalities’ or ‘euphemisms’ his lists codify the bricolage of his world: email correspondence, media reportage, academic essays, road signage, literature and mundane conversation.[5]

In one of the artist’s more literal agitprop pieces, Lewis shares some insight into the frustrations of inaccessibility and the experience of hindered movement, a rare, seemingly direct narrative of the experiences of people living with disabilities. Lewis’ bodily movements, whereby he uses his physical disability as a tool for creation, features in the work Banalities for the Barricades, (2005). Again, it cleverly combines many aspects of the artist’s practice: concrete poetry, performance, place, civic space, objects of culture. Banalities for the Barricades repurposes council barricades into text-installations placed to prevent access and free-flowing movement of visitors. As the artist walks through, with difficulty, speaking as he does in tongues of indecipherable rage (his signature glossolalia and sound poems—a translation of emotion if not logical semantics), he alone shifts the barricades to create new pathways, closing them again on others who would consider following him. Initially performed at G&A Studio Sydney, it was later performed more aptly in a public street: a civic setting being the natural habitat for the municipal message sticks, props, and the political nature of its message.

There is always more to a Lewis than one can first absorb. Sleep on it, it might hit you in the morning, or sometime in the future, with a jolt. Of course, Barricades is more complex than reading it as an experience of a dis-ability, de-sign; it is also a mis-reading. The barricades are props, cue cards, for performing improvised poetry. The voice, sound, is a vital component for Lewis. A practice he likens to Dada vocal sound poems.

I’m more interested in breaking language in an abject sense, so that the voice is produced between sound and noise to form a dissident and abstract outcome. Perhaps the shock of disabling something as primary as the tool of communication interests me more than some logical conceptual form.

It interests him so much he includes it in his everyday life. As he chats and reminisces, his observations of being observed are mentioned. As Ruark walks, with canes (let’s describe it as shuffling, sprauchling), his long silver hair possibly uncombed, his astute observation skills razor sharp, entering stores, requiring service … Interactions do not necessarily match his intellect nor agency. To complete the ‘project’ of being served at a local store, he unexpectedly roars in incoherent glossolalia. Another afternoon of making art. Even if it is just to an audience of one shocked shopkeeper and a couple of local customers.

Having a visual disability means you can’t pass, we can’t just walk down the street without being noticed and gawked at. I go to the shop and I get the most appalling treatment. If you arrive at the counter and you are puffing, or stagger in and just want the most simple thing, (not always…) but, they think this person has a mental illness and physical illness. I find I put it into some of the performances. I could go to that counter and talk in tongues to them, and I’ve done it on certain occasions and got preferential treatment because of it. It is amusing for me. And hopefully the rest of the audience find it amusing too, or are horrified.

In Cronulla, that was part of the game plan.

The semantics of agit-prop devices in civic spaces reached pertinent heights with Euphemisms for The Riotous Suburb (2007), a performance for video activation whereby Lewis again utilises his body identity: appearance and movement, for public transmission. Over the course of days/weeks, in different locations across the Sydney suburb he knew as his childhood home, he tied one end of a 2.5 metres-long beam (the barricade props) to his hip, attached wheels to the other end and walked the streets, park, beach of Cronulla. Wheeled wooden mobile concrete poems, with municipal crosses to bear, plus a couple of walking canes so he could perambulate. This can be read/received as an overtly political piece in response to the Cronulla race riots of 2005. But, there’s more: literary, absurdity, physicality, as the artist reveals, he often works with three elements, using them as a divertimento, so that the formula suspends the audience expectations of the work.

This video performance will be included in the exhibition Other Body Knowledge, curated by Jane Trengove and Katie Ryan at KINGS Artist-Run, Melbourne in September 2022.[6] However, the 2007 work began in 2005, attracting the artist’s full attention by way of place, culture, and a new technology for communication: the digital age of SMS and internet commentary. The performance video is part of a series of works, beginning the day after the riots. Lewis immediately wrote a libretto based on what was posted on the website MSN9 the following day. At that time, the internet and new form messaging enthralled Lewis. He could see the future, amplified voices wielding power never before seen, angering, inciting. The Alan Jones’ of 2005 set a template we still see played out too often. There was a real danger on the streets then, particularly for sharp-witted, strange-walking agitators with dark humour carrying visually loud concrete poems such as:

I AM FROM A WOG BACKGROUND

NOW PEOPLE ARE SCARED

MONEYMONEYMONEYMONEY

THE TYRANNY OF DISTANCE/THE DISTANCE OF TYRANNY

Absurdity can frighten some people, delight others. In Cronulla the artist was visible/not visible, ‘there was a micro recognition on their faces of what was going on, you can see it in the video, but no-one demonstrably interacted with me. As I pass in their zone they avert their eyes, because the disability masked me, I was visible but in theory I was invisible to them, they just rubbed it out, it’s not happening, it’s absurd.’

It is gloriously incongruous to watch him as he monopolises space, a semi-trailer of a moving object along the main shopping strip, through family picnic camps, past half-naked swimmers at the beach. At times he falters, his foot drags with weariness, he must pause and rest. Watching the video, further subliminal text frames are barely noticed, sourced from the new digital community noticeboard responses of the day, literal micro-frames of less than a second which you cannot read unless freeze-framed:

do not try to change us

first I’d like to state

politicians who grandstand

I welcome anybody who feels

now things got worse

good on the boys in Cronulla

I never felt less Australian

And ends with:

to all you racist people

INTERPOLATION. SYNCOPATION.

In 2011 while on Yolngu Country visiting long-time friend and collaborator Barayuwa Munuŋgurr, Lewis was badly injured and required hospitalisation. He spent ten weeks in a Darwin Hospital bed in an isolated room. This is the artist at work. Within days he had created a hospital room art studio, (our own post-op Matisse!) utilising materials at hand. His practice at this contained, intimate level reveals his insatiable intellectual drive to create, to transform thoughts into concept into outcome.

Well, the first thing was I didn’t have paper, but if the food came on the tray and they hadn’t spilled anything, I got the piece of doily paper from underneath, so I was able to draw on those three times a day, and I had a fountain pen. I’ve got the drawings, they’re wonderful and hesitant and it took a lot of effort. And that’s when I started doing the Star Shelter drawings. I had done these drawings on ceramics in the eighties where I’d adapted this triangulation to new vector forms.

The physical restrictions he experienced led to adaptations, creative evolutions, having no perspectival vision of the world for weeks on end, he had to draw while lying on his side, which changed the way he could see and draw depth into a work. Eventually he did have access to paper, the doily experiments evolved into the Hospital Drawings, pen and ink works on paper 21 x 15 cm in scale. They are dynamic monochromatic line drawings of expanding, collapsing forms that, already at this stage, feel sculptural, ready to leap off the page.

Germinating alongside this aesthetic direction was the influence of Dianne Johnson’s book on Aboriginal astronomy Night Skies of Aboriginal Australia: a Noctuary (1998) and conversations with the anthropologist herself. This concept was also nurtured by theories of architecture, a discipline of ongoing interest to the artist, having been mentored by Australian architect Bill Lucas and a lifelong simpatico to modernism (and modular-ism) as it translates through theories of architecture and socialist vernacular. The Star Shelters were commissioned and made for the artist’s survey show at Hazelhurst Gallery in 2012. Drawing parallels with Munuŋgurr’s teachings on Yolngu shelter, how it is built and dismantled and moved—the purpose and philosophies around ‘shelter’ offers new ways of thinking and incorporating what housing can be: temporary, autonomous, mobile, free.

The hospital as studio. Again.

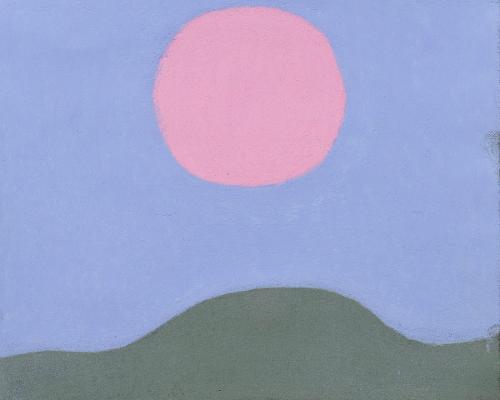

The Meander Paintings have emerged from a more recent hospital stay. On grid paper Lewis was replicating some of Anni Albers’ work, random mazes, architectural drawings, and found himself in grids. The labyrinth, the interlocking Greek key motif, MEANDROS, the river flowing, meandering, Ionia, Ionic columns, the god Oceanus, Oceania. Turning away from the regional, looking to historic Europe, somehow winds back to the regional. They are to be a part of a forthcoming exhibition at Charles Nodrum Gallery, called Durational Painting.

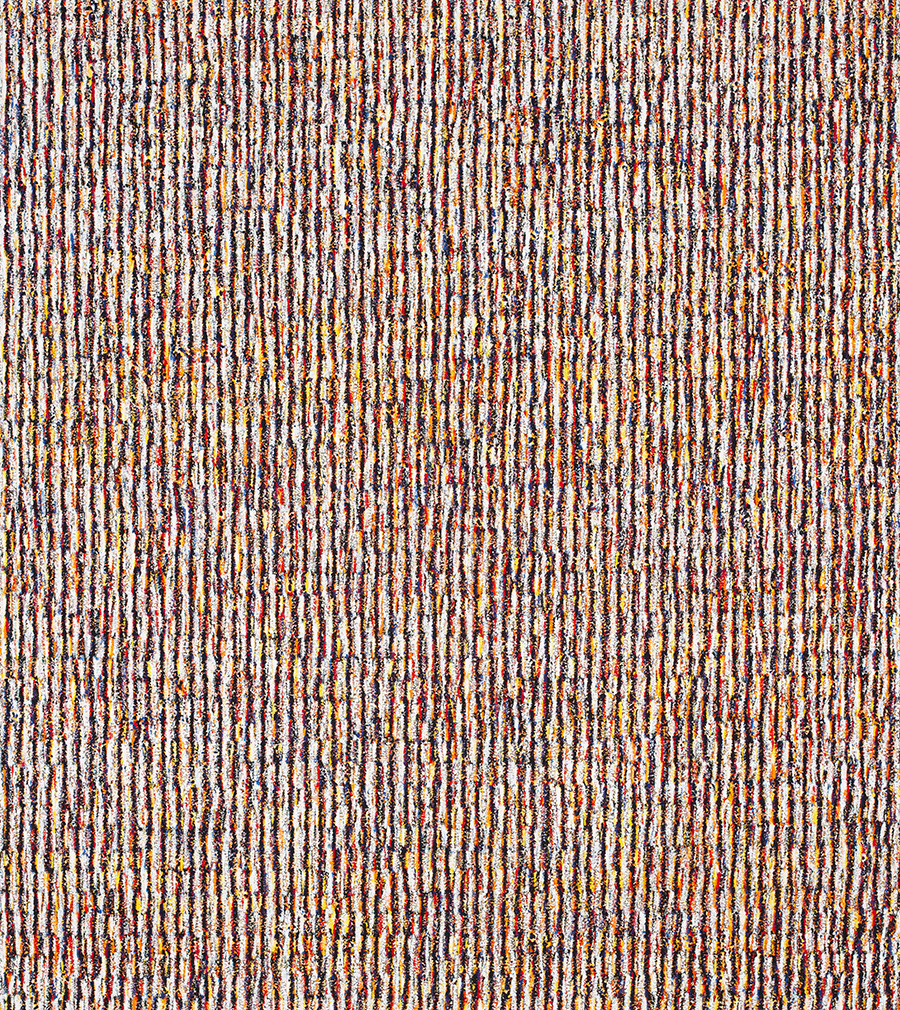

Since those grand eloquent works the scale of my performance pieces have become more modest, especially as the text I was interested in writing became less theatrical/musical. In the last couple of years, I have become fixated on durational pieces. Durational writing, durational paintings. Sequencing and serial systems pieces. These I now find more sustainable as my physical power diminishes.

Lewis hasn’t been to his studio since the start of the pandemic. He does not go outside; the risk is too great. His living space is now his studio, and he has assistance from Tom Sandberg, to help him prepare and move canvases. Aesthetically abstract, traditional in medium and format, conceptual in nature: they are sonic, literary and time-based paintings. In essence, a continuation of the artist’s wildly experimental creative compulsions.

There are four recognised series being presented:

Aniaaniaania series.

Speedy paintings.

Interval paintings.

Meander paintings.

I was telling my Pilates therapist today how such details of these seemingly abstract (non-representational) paintings amuse me. It amuses me that I can calculate, measure, and chromatically devise every single stroke in such pieces. Their durational nature is highly considered yet the haptic character of each single physical stroke of the hand in these cells function combined to transmit optical vibrations or qualities very much human.

Subtle designs can be discovered within the pigment of the durational paintings, made in rhythm to poetic beats. In Meander Paintings Lewis was listening to poet/composer Chris Mann’s (1949–2018) sound mixing program, creating unique compositions using Mann’s voice as notes and chords. Speedy Paintings holds the voice of poet Ania Walwicz (1951–2020), private recordings made in 1982 of surreal poems Photo and Jesus. He is conducting the voices of his absent friends into the surfaces of the canvases.

All the durational paintings are made by hand—literally, the finger, and an oil pigment encaustic wax. If I felt the artist was hard to find, here he has quite literally marked himself within the surface of the painting.

Footnotes

- ^ Ruark Lewis: http://ruarklewis.22web.org/ accessed May 2022__

- ^ Lewis in conversation with the author, 29 May. All subsequent quotes by the artist, if not otherwise cited, are from conversations and email exchanges between 12 April and 29 May 2022__

- ^ Descriptions and photographic documentation of Banalities: Banalitän can be found in Thoughtlines: The art of Ruark Lewis, 1982–2014, James Paull, SNO Publishings Sydney, 2016., and Keith Gallasch, “Expanding the cultural universe” RealTime #55 June–July 2003__

- ^ Ruark Lewis interviewed by Keith Gallasch, RealTime #87 Oct–Nov 2008__

- ^ Paull, 123__

- ^ Artlink, Sensoria: Access & Agency, 42:2, Wirltuti / Spring 2022: 66–75.